We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

What to expect from Nigeria’s IT roadmap

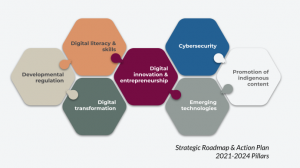

In April, Nigeria’s Minister of Communications and Digital Economy Dr Isa Ali Ibrahim Pantami unveiled the country’s digital economy masterplan for the next three years. The Strategic Roadmap and Action Plan (SRAP) 2021-2024 was developed by the National IT Development Agency (NITDA), the main IT regulator in Nigeria.

Seven pillars

Delineated across seven pillars, the SRAP is the implementation plan for the government’s National Digital Economy Policy and Strategy (NDEPS) 2020-2030. NDEPS is the main operational document informing government policy in this space.

While each strategic pillar has defined goals to be met by the end of 2024, the objectives and performance targets are less clear. There is also no visibility on when each initiative starts or ends, which sets the stage for difficulties in tracking progress and fostering accountability. There are also three key areas, outlined below, which remain somewhat unclear as defined by the SRAP.

Furthermore, a review of the SRAP’s formulation strategy reveals that the policy was designed and conceptualised solely by NITDA – without due consultation of non-governmental ecosystem stakeholders. Only after the SRAP was launched did the agency embark on a three-day sensitisation campaign in Lagos State. As such, the expectation that the SRAP will be implemented via “NITDA partnership actions” alongside “third-party actions”, suggests a keenness to foster external collaboration, but simultaneously demonstrates a degree of disregard of the ecosystem’s priorities.

Forthcoming restructuring

According to the SRAP, NITDA would be restructured, including through the creation of a new department of digital economy within the agency, as well as the redefinition and refocusing of other departments. To date, however, there is little further detail on the exact parameters of the restructuring.

Cybersecurity and payments

While the agency clearly recognises Nigeria’s critical cybersecurity challenges, it appears to do this in a silo, without reference to the coordinating authority for cybersecurity – the Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) or the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). ONSA in February 2021 released a cybersecurity policy and strategy, while the CBN issued a risk-based advisory framework covering payment, clearing and settlement activity. The proliferation of such initiatives reinforces how little government agencies prioritise collaboration and reflect the wider fractures in Nigeria’s policy-making processes.

Despite an uncertain landscape in respect of blockchain enabled-currency, the ubiquity of blockchain and its potential future benefits for both the public and private sectors are becoming apparent. Therefore, it is not surprising that NITDA intends to “develop a framework for the adoption of national blockchain technology and strategy”, in order to “understand and advise the populace on blockchain technology”.

The focus on ‘understanding’ blockchain technology here is crucial. In a space where other government actors have sought to regulate and intervene without proper understanding, the agency’s acknowledgment of its capacity gap is unusual and notable. Again, however, there are no timelines or more concrete plans associated with NITDA’s expected learning phase.

Data protection

Another notable initiative in the SRAP is for NITDA to “develop a framework for implementation and compliance [with] relevant regulations […] such as NDPR” among others. A draft executive bill currently in development suggests that the establishment of a Data Protection Commission (DPC) may be imminent. NITDA may not expect the bill’s imminent passage, but seems to expect to retain oversight of data protection compliance, despite the DPC’s establishment; this could potentially create a parallel regulatory structure.

Ensuring implementation

Ultimately, the development of the SRAP – delineated across clear workstreams, with specific departmental accountabilities – underscores the government’s commitment to prioritising and accelerating its digital economy agenda, which was initially spearheaded in late 2019. The success of the action plan, however, will rest on NITDA’s ability to set more definite performance measures on an annual basis, and implement an effective and iterative feedback mechanism.

Other extraneous factors, including political attacks on Pantami, may impede implementation, particularly as the 2023 presidential elections approach. NITDA thus faces the task of managing a fracturing political landscape, while rallying internal and external stakeholders to achieve its vision.

About the author

Amaka Yvonne Onyemenam is a Consultant at Africa Practice focusing on the digital economy and technology policy in West Africa.

Related articles

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more