We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Reimagining industrialisation in Southern Africa

The decline in mining output in South Africa over the last five years reflects a broader de-industrialisation taking place in Southern Africa, where the contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP has been decreasing since 2009, when it stood at 13.1%, falling to 10.7% in 2019. At the same time, intra-regional exports – as a percentage of total exports – have remained stagnant at 20% over the last five years.

These figures should concern all residents of the region who rely on the development of industries on a large scale to unlock employment, increase incomes and raise living standards. Several reasons exist for this relative de-industrialisation, including corruption, power supplies, soaring costs, poorly capacitated state-led development planning and poorly regulated markets. But perhaps the greatest factor has been a failure of policy and vision.

To address our unemployment crisis and raise living standards, we need to reimagine our industrialisation and make it relevant for the local and global context. We have to ask ourselves what competitive advantages we have as a region, how to harness them and what we want our countries to look like afterwards, and then co-create the right policies in consultation with the private sector, to pursue it.

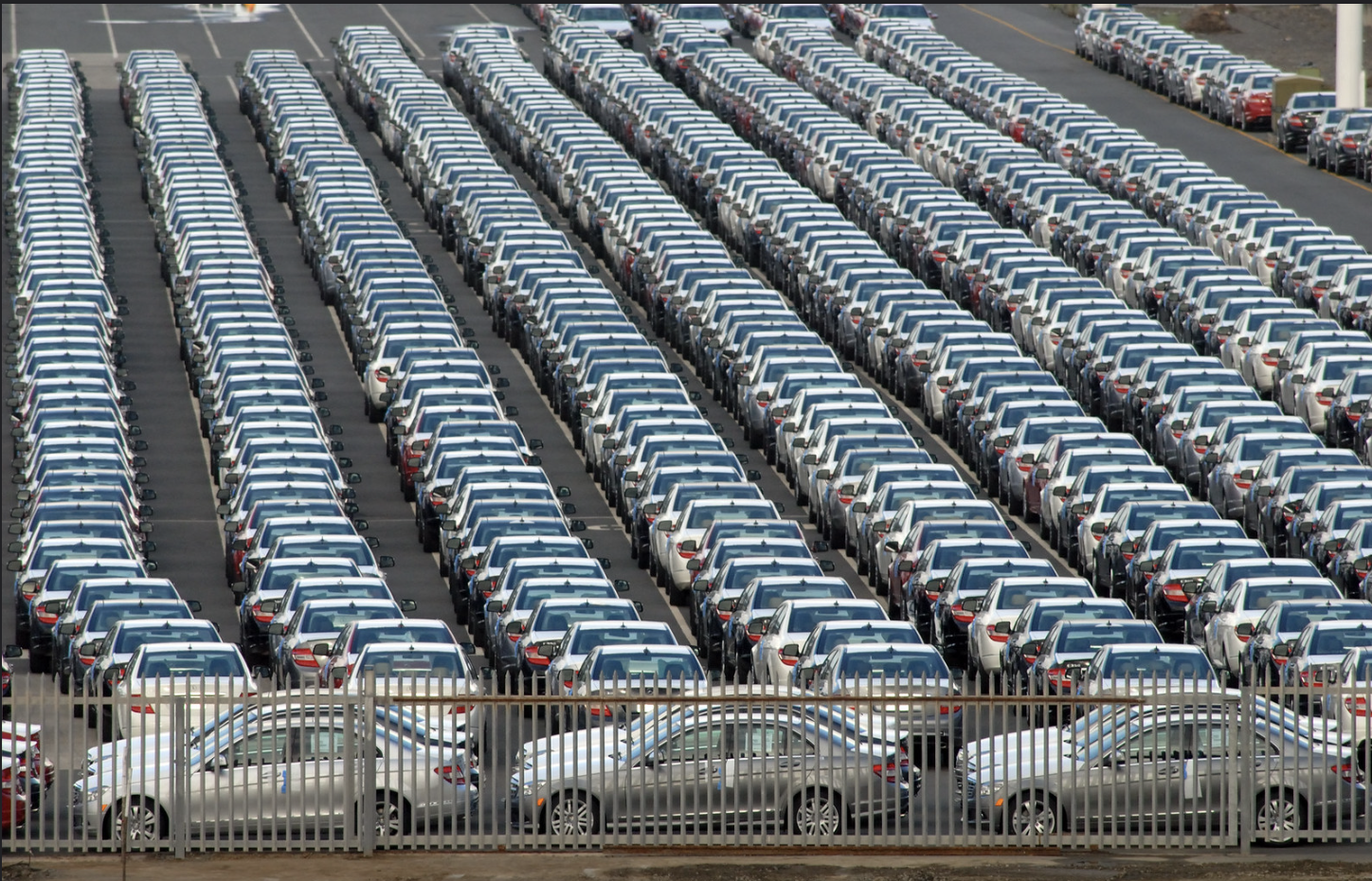

Today most Southern African economies are characterised by the export of raw materials with little or no added value. Too much of what is consumed in our region is not produced in our region, so we are continuously exporting and reimporting. We pay for the export freight of raw materials and for their way back after the value addition, which is expensive, and we export the jobs that are created from value addition in the process.

Imagine instead if our region’s natural resources and energy were used to transform our societies from exporters of raw materials with little or no added value, to competitive manufacturing and services powerhouses. We have a wealth of natural resources to accelerate our transition. Our minerals and metals, for example, have a critical role to play in providing the materials that are needed for a low carbon world and to accelerate the 4th Industrial Revolution. Our agricultural industry holds immense potential too, but only if we can establish the tax incentives, tax penalties, regulations and funding to ensure that processing takes place in our region – creating hundreds of thousands of jobs and securing billions of income lost to offshore processors. A full embrace of free trade across the region would help to establish SADC as a viable alternative to manufacturing in China and elsewhere, for companies that are prepared to meet rules of origin provisions. A strong regional market would reduce the carbon footprint from global shipping and create essential jobs for our young population.

It’s policy, not politics that will drive prosperity into the future

The good news is that as a relative latecomer to industrialisation, we can adopt alternative pathways more quickly and more cheaply than OECD nations. But to do so, requires our governments to be very clear on the drivers, challenges and trade-offs in pushing for green industrialisation, and the merits of pooling resources and integrating value chains for scale, cutting across national boundaries.

And let’s be clear about the imperative for doing so. The preeminent challenge of our time is decarbonisation, and the preeminent preoccupation for industry is to realise scale. Whether we like it or not, this has implications for our entire economic system. A ‘business as usual’ approach to industrialisation won’t work. We must adapt to the new rules of the game or risk getting left behind. A failure to reimagine our industrialisation and build back both better and differently from the pandemic, will only see poverty proliferate.

Inclusive policymaking

The systemic changes required will need consensus between socio-economic groups and government, and even between government agencies. We need more collaboration between governments and economic actors. We need to be capable of leveraging global communities of knowledge to design policy and realise innovations with the potential to mainstream– from products and services to entirely new ways of operating.

The stakes are high and transitioning our economies will not be easy. It requires a shift in production towards high-value added, higher productivity, and higher-skilled work. It requires coordinated changes in ways of operating, value attribution and infrastructure that can only be achieved with policies that reflect an empirical understanding of our opportunities and which touch on almost every aspect of economic and human development planning, and investment.

Everywhere we look, the economic cost of not acting is higher than the cost of acting. It’s time to reimagine what industrialisation looks like for our region, design the appropriate policies, the appropriate regulations, remove the costs driving non-tariff barriers, and mobilise the attendant technologies and capital to transform our societies. While governments and regional bodies undoubtedly need to lead in this endeavour, this should not be the preserve of governments alone. We need a broad coalition of the best talents available in Southern Africa, and we need to leverage economic tools like taxation and subsidies, as well as political and legislative tools, to co-design policies and shift economic incentives. The Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Secretariat and the SADC Business Council have an important role to play in making this happen, and they can draw confidence and build momentum for change bolstered by the high number of nations within the region that have ratified the AfCFTA (African Continental Free Trade Agreement). The AfCFTA can be a powerful tool for industrialisation, by removing tariffs and facilitating cross-border value chains.

The scale of the challenge is significant, but with the appropriate political and social will to get on the front foot and forge our own future as a region, reliant on the taxes that we generate, not the aid or debt that we accumulate, we can chart our own destiny – free from poverty.

About the authors

Co-authored by Marcus Courage, CEO of Africa Practice, and Ian Hirschfield, Director of Economic Policy at Coca-Cola Africa.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more