We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

COP27: No love lost

The “African” COP27 delivered on a big promise, the loss and damage fund, three decades after small island states first raised the issue. Vulnerable populations at the frontlines of the climate crisis – mostly in the developing world – are now poised to receive financial assistance from richer countries. Some saw the agreement as resetting the “rich-poor balance”.

But the deal also highlighted the deepening global rich-poor divide. There is no love lost between the countries in either “camp”, as the polarising and prolonged deliberations in the final hours of COP27 showed. The trust deficit between the developed and developing world remains stark, even as many heralded the historic agreement, symbolically reached on African soil. As the Maldives’ Minister of Environment Aminath Shauna poignantly asked, “Why are we celebrating loss and damage when we have failed on mitigation and adaptation?”

As the world readies for COP28 – to be hosted by the United Arab Emirates, one of the top ten global oil exporters – we will keep tracking three core issues:

Finding the funding

The next 12 months will be critical to defining the financing parameters for the fund, the extent to which these meet developing countries’ expectations and those of contributors. Against an increasingly complex geopolitical backdrop, it will be telling to see whether China and certain oil producing nations join the developed countries in mobilising funds.

The developed world’s track record in delivering on its promises is, well, poor. The 2009 pledge to mobilise USD 100 billion in annual climate finance for developing countries by 2020 was never fulfilled. Between 2020 and 2030, the annual climate finance gap, including loss and damage, is projected at USD 250 billion. At the end of 2022, some of the world’s leading markets are entering not only a projected recession, but potential structural shifts and financial fragility.

Africa’s seat at the table

The loss and damage breakthrough can be attributed, among other factors, to the assiduous advocacy since COP26 from African governments and civil society, representing more than 1.2 billion people. Ten-year-old Ghanaian activist Nakeeyat Dramani Sam made a compelling case for youth to have its own delegation at COP28, delivering a tour-de-force speech to delegates.

African leaders are now emboldened to double down on their efforts to seek more representation. Immediately after COP27, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa called for the AU to join the G20 at the G20 Leaders’ Summit held in Bali, Indonesia. Africa is the only region without permanent UN Security Council representation; the council’s legitimacy will continue to be called into question without permanent African representation.

Africa has also committed to double the issuance of carbon credits by 2030 through the creation of an efficient African carbon and biodiversity credit market with a determined price floor, integrity credits, interoperable platforms and transparency. The African Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI) was launched by Kenyan President William Ruto, aiming to build a thriving voluntary carbon market ecosystem. It aims to help African nations mobilise up to USD 6 billion annually by 2030, and more than USD 100 billion by 2050.

But amid global economic turbulence, sub-Saharan Africa is expected to grow by only 3.2% in 2023. Meanwhile, India, which unsuccessfully called for a phasedown of all fossil fuels, is expected to demonstrate the world’s second highest GDP growth rates (6.6%), after Saudi Arabia.

The fossil fuels bottomline

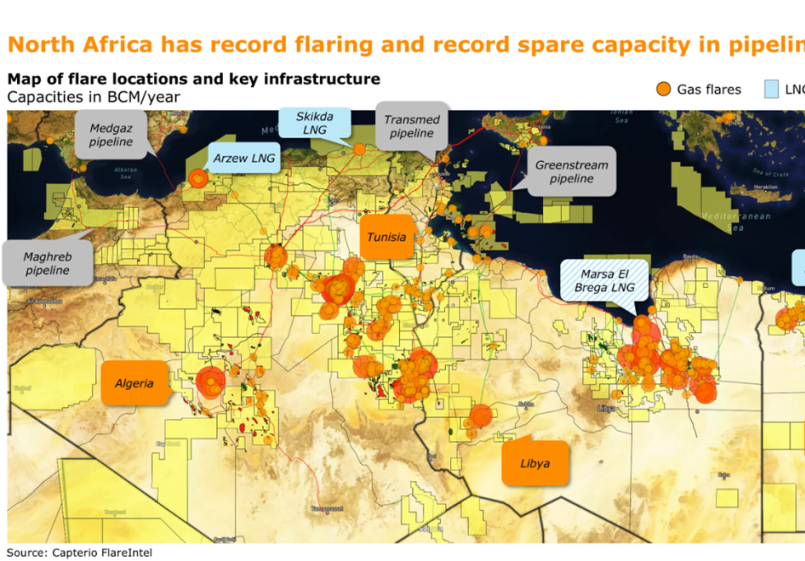

The loss and damage fund success was – again, quite starkly – contrasted with the disappointment of a number of developed and small island nations’ leaders regarding the phasedown or phaseout of fossil fuels. Several African countries are eager to exploit their reserves, rightfully arguing that the current climate state of affairs is not of their making. “Africa wants to send a message that we are going to develop all of our energy resources for the benefit of our people,” in the words of Maggy Shino, Namibia’s petroleum commissioner.

Several of Africa’s leaders argue that fossil fuels — and in particular, natural gas — are still needed to meet energy demands, as renewables remain intermittent. “Africa must have natural gas to complement its renewable energy,” is the position of the African Development Bank president, Akinwumi Adesina. He argued that even if the continent tripled its current production of natural gas, it would only see a 0.67% increase in its contribution to global emissions.

As another deep global faultline develops, a total of 636 fossil fuel lobbyists – a 25% jump from last year – are reported to have attended COP27.

About the author

Dr Margarita Dimova is a Director at Africa Practice, where she leads the Intelligence and Analysis team. The above represents her views and not those of Africa Practice. Margarita can be contacted at [email protected]

Photo credit: Peter Dejong/AP Photo

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more