We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Digital self-sabotage: The cost of internet shutdowns in Africa

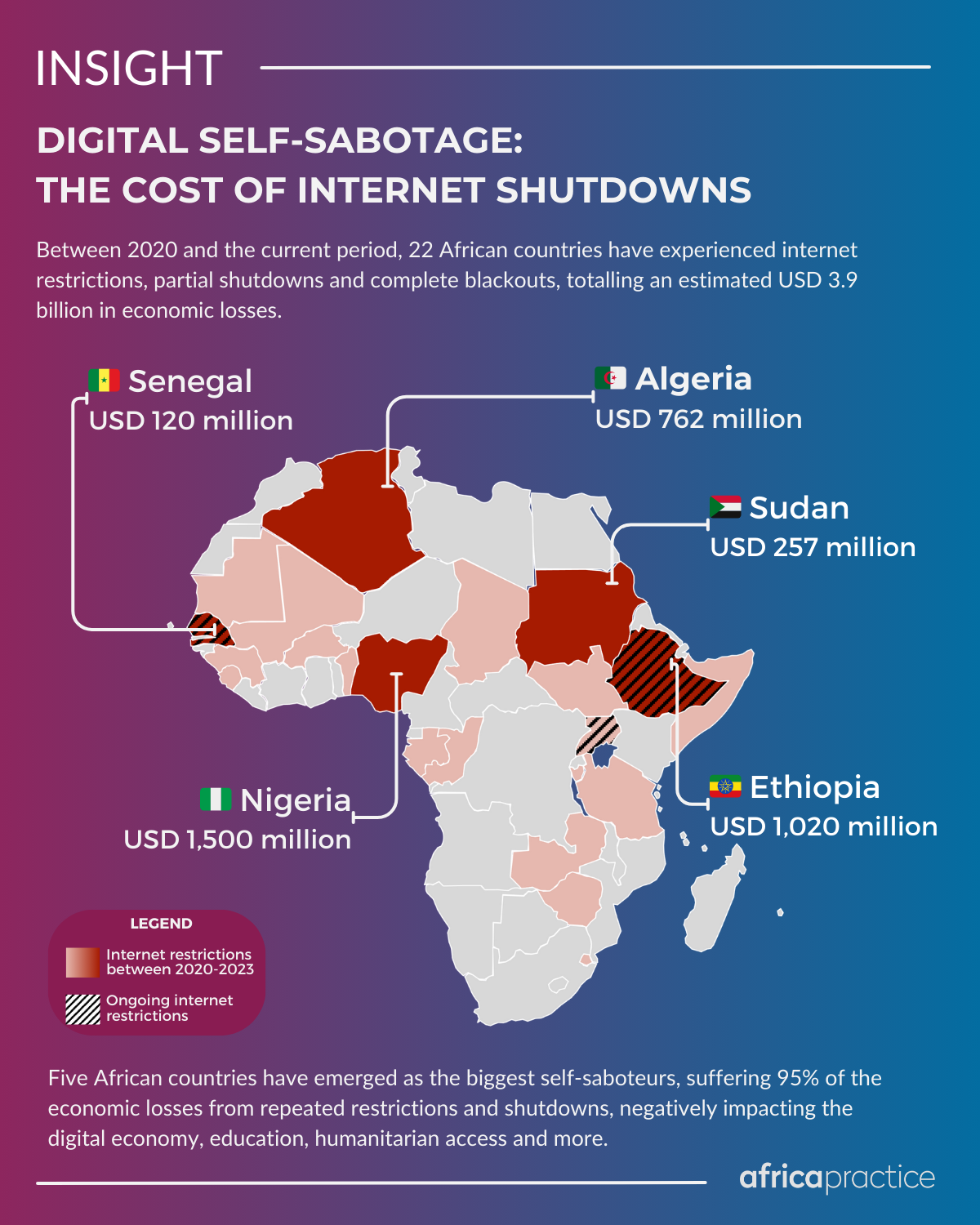

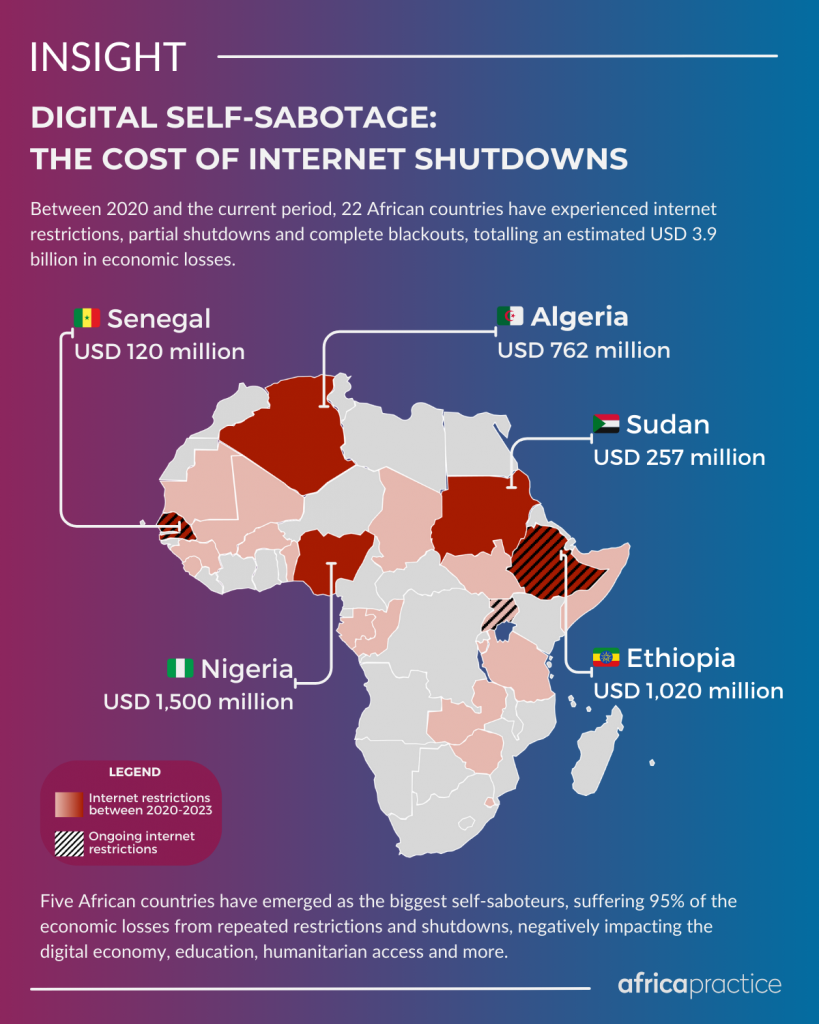

Between 2020 and 2023, at least 22 African countries have implemented complete or partial internet shutdowns. These straddle the continent – from Algeria in the Maghreb; to Senegal, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Togo, and Nigeria in West Africa; Chad, Gabon and the Republic of Congo in Central Africa; Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Uganda, Tanzania and Burundi in East Africa, and Eswatini, Zambia and Zimbabwe in Southern Africa.

These restrictions are often justified under the guise of protecting national security, and criticised for their incursions on fundamental human rights – including freedom of expression, access to information, and the right to peaceful assembly. However, internet shutdowns also contradict governments’ stated commitments to the development of the digital sector, and between 2020 and 2023 caused an estimated USD 3.9 billion in economic losses, according to our calculations.

The rise and whys of internet restrictions

Since the first incident of an internet shutdown in Africa in 2007 – following calls for the then-president of Guinea, Lansana Conté, to step down – African governments have used social media restrictions, and partial and total internet shutdowns for a range of causes. Analysis of all incidents of internet restrictions on the continent between 2020 and 2023 exposes two interesting findings.

First, while most internet shutdowns are inherently political, primarily aiming to protect national security from perceived threats, a number of countries including Algeria and Sudan have regularly restricted the internet for one specific aim – to curb cheating during school exams. In Algeria, the use of internet blackouts to stop tech-savvy high school students from cheating has outpaced its use for national security, but this has still inflicted extensive economic damage, estimated at USD 374 million between 2020 and 2023.

Second, the growing importance of the digital economy, evidenced through the growth of various countries’ digital sectors and the increased prioritisation in public policy-making, means the economic cost of internet shutdowns is only rising. Paradoxically, of the five countries which have experienced the largest negative impacts of internet restrictions – totalling USD 3.6 billion between 2020 and 2023 (see map above) – all bar Sudan have prioritised the development of their digital economies in a bid to become continental leaders.

Unravelling the policy paradox

Such extensive economic damage incurred by internet shutdowns in countries that are ostensibly committed to strengthening their tech sectors raises questions over the sustainability of Africa’s digital development. Nigeria, Senegal, Algeria and Ethiopia were digital pioneers before securocrats encroached on local tech ecosystems.

Nigeria and Algeria are the African countries with the highest number of active startups, according to rankings, thanks to their wide base of young digital-first innovators and entrepreneurs, and emerging policies to enhance collaboration and support from the public sector. Both countries are among the first in Africa to implement startup acts. In Algeria, the creation of a dedicated legislative framework resulted in public banks deploying DZD 510 million (USD 3.7 million) in startup funding between 2021 and 2022. In Nigeria, the new Minister of Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy Bosun Tijani – himself a “tech bro” as former CEO of Co-Creation Hub – has set out a new strategic blueprint in a bid to enable a new age of public-private collaboration.

In Ethiopia, the government’s long-awaited liberalisation process has focused on the digital sector, and the Digital Ethiopia 2025 Strategy identifies e-commerce as a priority for economic growth, aiming to leverage the logistics expertise of Ethiopian Airlines to make Addis Ababa a regional hub. The state-mandated digital revolution has seen state-owned mobile money platform Telebirr register over 34 million users since its launch in May 2021, processing over ETB 161 billion (USD 3 billion) in transactions between July 2022 and January 2023.

Senegal is also in the process of a digital transformation, aiming to grow the digital economy’s contribution to the GDP from the current 3.5% to 10% by 2025. To enable this, the government launched the National Data Strategy in July 2023, followed by a National AI Strategy in September – both drafted with technical support from the European Union.

Solutions to navigate the digital age

The extent of the economic damage caused by internet restrictions creates an urgent imperative for African governments to identify alternatives that balance the control of unwelcome digital activity with development objectives.

While Algeria’s internet restrictions have been focused on tackling rampant instances of cheating in education, the country is not alone in noticing that digital innovation has facilitated cheating in the new generation of students. Frequent exam leaks and the rapid rise of AI use for assignments has seen educators around the world question whether current curriculums are fit for purpose in the new digital age. The outsized impact of exam-related internet restrictions on Algeria’s economy should urge the government to revamp state curriculums and evaluation methods, bulletproofing the system against students who continue to outsmart teachers and policymakers.

Former Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari’s strict approach to unwanted public discourse on Twitter gained his administration a reputation as an enemy of digital-first innovators and small businesses. By contrast, his successor, Bola Tinubu, has recognised the need to nurture Nigeria’s digital talent – both at home and in the diaspora – as exemplified by the appointment of Bosun Tijani as head of the digital ministry. He plans to upskill three million early to mid-career technical talents over the next four years, aiming to take advantage of the International Finance Corporation’s projections that Africa’s internet economy will hit USD 180 billion by 2025.

In Senegal, the government has agreed to come to the negotiating table with TikTok in order to lift a suspension of the social media platform which was put in place following demonstrations in August. Though reactive rather than proactive, the government’s demands for TikTok to establish a physical local office will better enable collaboration to mitigate future issues, while also highlighting emerging concerns on data sovereignty echoed across the continent. This focus on collaboration should extend to the local private sector, to support attempted initiatives by telcos and mobile money operator Wave to ensure continued access to basic services during trying times.

In Ethiopia, this danger goes beyond immediate impact, to the resulting wariness and distrust that can emerge following extended restrictions. The blackout in the regional state of Tigray remains the longest internet shutdown in world history, totalling 670 days from November 2020 to December 2022, and Tigrayans reconnected to a vastly different digital landscape. So far, efforts to push Tigrayans to resume use of banking services has proven difficult on account of lingering distrust in EthioTelecom and the government, spelling trouble for Telebirr’s uptake in the region. Officials should consider the impact of distrust as it upholds the ongoing blackout in Amhara, implemented in August 2023.

This serves to illustrate the inadvertent consequences of internet shutdowns, which have a propensity to create cyclical issues that sabotage governments’ public policy objectives, strangle the digital economy, and undermine the social contract.

About the authors

Jasmine Okorougo is an Associate Consultant at Africa Practice with a special focus on political economy and digital financial service developments across sub-Saharan Africa. She can be reached at [email protected].

Ujunwa Umeokeke is an associate consultant at Africa Practice, advising clients on digital economy and tech policy developments in West Africa. She can be contacted at [email protected]

Related articles

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more