We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

South Africa’s precarious industrial balancing act

South Africa is caught in the crossfire of two major global policy shifts that collectively threaten to destabilise already fragile industrial sectors.

First, the European Union (EU)’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) became law in 2023, with implementation planned for 2026. CBAM has forced high-emissions industries to develop decarbonisation plans, threatening the viability of facilities across the Global South, where governments have less latitude to subsidise upgrades. Despite discussions in Brussels about delaying the implementation of CBAM and adjusting its scope, the policy hangs over African industry like a sword of Damocles.

Second, the Trump administration adds another degree of complexity, with echoes of the early-2000s “steel wars” and his first term in office. Trump’s recent threat to impose a 25% tariff on all steel and aluminium imports may represent an extension of his 2018 measures, but it also threatens to drive producers out of business. Plans for a circa 25% tariff on imported cars further weigh on the sector.

Indian steelmaker ArcelorMittal relies on the US for 13% of its sales, leaving it highly exposed to Trump’s tariffs and short on revenue to reinvest in ageing facilities. In South Africa, ArcelorMittal plans to close two of its biggest steel mills, Vereeniging and Newcastle, and a rail production facility, barring government support. ArcelorMittal’s closure is expected to result in approximately 3,500 direct job losses and has raised concerns about the broader impact on the country’s economy and industrial capacity.

European regulatory pressure

CBAM – which imposes a cost on the carbon emissions embedded in steel and other products – alone did not trigger ArcelorMittal’s move to close loss-making facilities. Still, the prospect of additional regulatory pressures from the EU and USA has exacerbated deeper, long-standing concerns about the industry’s global competitiveness. South Africa’s steel sector remains hampered by ageing rail and port infrastructure, fierce international competition (particularly from China), and growing tensions between operators using iron ore to make steel and those using scrap metal.

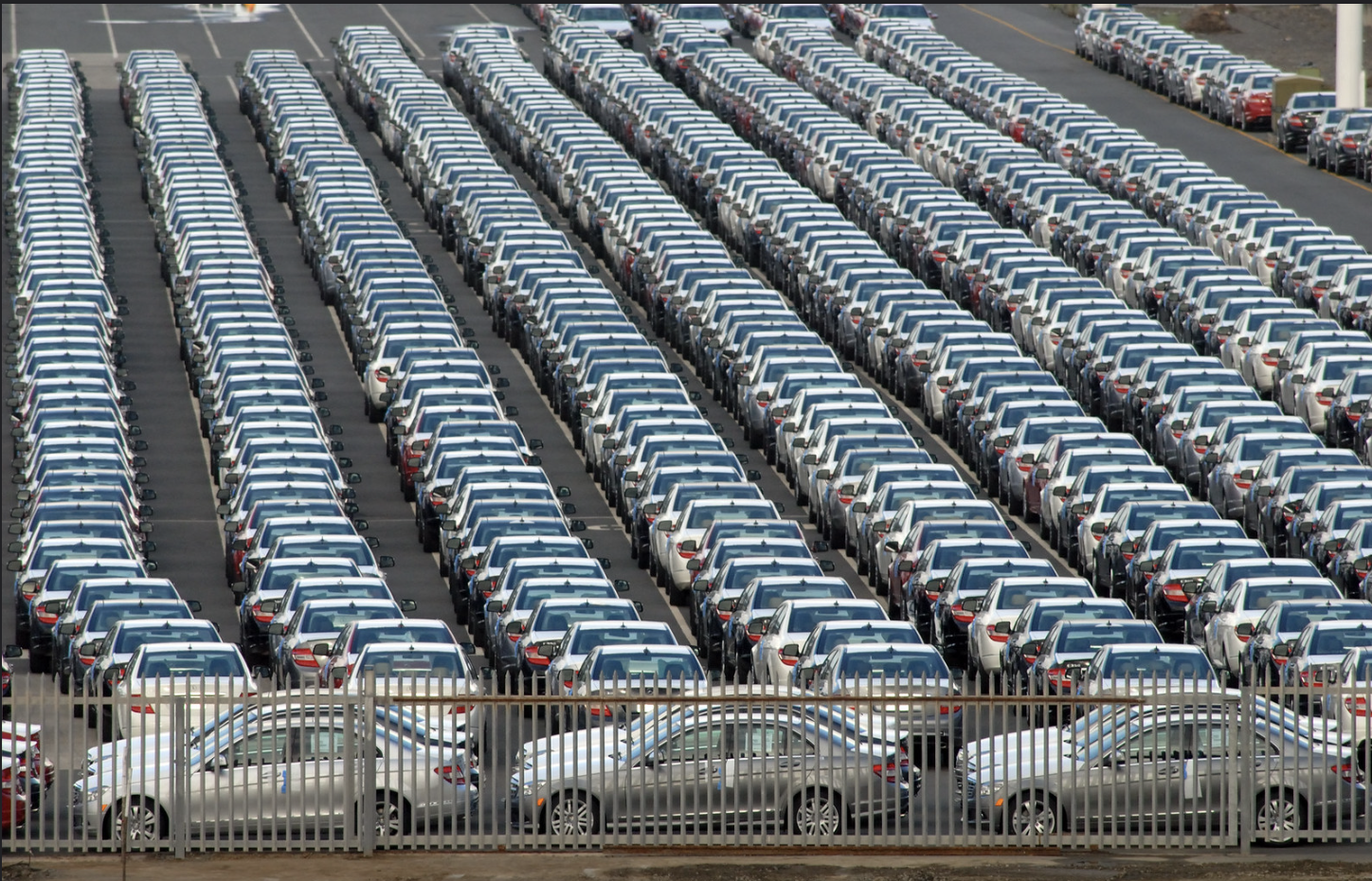

Crucially, South Africa’s reliance on coal for electricity generation and steel production threatens to expose its raw material exports to tariffs under CBAM, reducing its competitiveness in European markets. These markets account for nearly two-thirds of automotive exports, an industry central to South Africa’s economy. While CBAM does not yet apply to finished vehicles, its impact on steel and aluminium costs could indirectly affect automakers by increasing input prices and shifting supply chain preferences toward low-carbon alternatives. The European Commission plans to assess and potentially expand CBAM’s coverage to include manufactured goods like cars and trucks as soon as 2030.

Recent EU measures like CBAM and US protectionist tariffs are already disrupting established trade routes and compelling exporters to seek new markets. For instance, Indian exporters may refocus their efforts on South Africa – a move reminiscent of the early 2010s when shifts in US trade policies led India to redirect its exports toward emerging markets. These changes could reshape the global steel market and generate ripple effects across interconnected sectors as supply chains adjust to new cost structures and competitive pressures.

AGOA on the edge

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) faces an increasingly uncertain future – particularly for South Africa, whose proximity to Russia and stance on the Israel-Palestine conflict have raised concerns among American lawmakers. As a result, the U.S. automotive industry may soon need to reassess its supply chains. AGOA has been instrumental in supporting African automotive exports to America, with South Africa dominating the sector.

However, the impact of losing AGOA’s trade benefits would be limited – by 2022, motor vehicles accounted for only 10% of South Africa’s exports to the U.S., down from 25% in 2013. While estimates suggest that AGOA’s termination would reduce total U.S. exports by just 2.7%, assessments that minimise its significance must also consider the broader context.

CBAM is set to influence the production costs of essential vehicle components, adding another layer of complexity for South African manufacturers. This is particularly relevant given that the EU remains by far the primary market for South African-made cars.

Threat to local industry and jobs poses government dilemma

The stakes extend beyond steel as interdependent industries expose critical vulnerabilities in South Africa’s supply chains. Flexible spring steel is indispensable for automotive components, while the hollow variety is essential for hand-held mining drills used in deep-level precious metals operations. The sector indirectly supports over 100,000 jobs by supplying steel products that no domestic producer can match. Yet, the industry is in decline, squeezed by ageing infrastructure and impending regulatory pressures from the EU’s CBAM.

The ruling African National Congress (ANC), deeply entrenched in a legacy of interventionist industrial policies and allied with the powerful Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), faces a near-impossible balancing act: preserving jobs in a struggling industry while navigating a just transition towards lower-carbon production.

The government must support firms in establishing robust emissions reporting systems, negotiate transitional arrangements to allow industries time to adapt, and implement policies that accelerate decarbonisation while ensuring that carbon revenues are retained domestically to fund further green initiatives. Decarbonisation is the only viable path in the long run – to sustain exports, attract investment and secure a more resilient and competitive economy.

Image credit: Rodger Bosch

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more