We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

USAID Cuts: Six months on

This week marks a grim anniversary in the aid sector: six months since the announcement of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funding freeze on 20 January. Following a review of all USAID grants for alignment with American values and interests, 86% of USAID awards were terminated, representing USD 27.7 billion in global multi-year funding that had been committed but not disbursed.

For context, in 2023, USAID allocated a total of USD 12.1 billion to countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and USD 12.7 billion in 2024, equating to 31% of USAID’s foreign assistance for that year. Much of this was directed towards life-saving programming, including HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, maternal and child health, and nutrition interventions.

Forecasts of the life-altering impacts on the continent were dire: the Institute of Security Studies projected that the cuts could push 5.7 million more Africans into extreme poverty by 2026. Separately, the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) estimated that two to four million additional Africans are likely to die annually as a result of reduced global aid budgets. Within South Africa alone, cuts to HIV/AIDS programmes could result in an additional 500,000 deaths over the next decade, according to the Desmond Tutu HIV Center.

Which countries have been most heavily affected?

The chart below indicates the top ten African countries affected by the USAID cuts in dollar value, as per the 2024/25 fiscal year.

Figure 1

In dollar terms, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Ethiopia have seen the greatest cuts. However, their large populations and economic heft may obscure the true impact of the cuts, which may appear more visible in smaller and less diversified economies such as Mozambique and Mali, where USAID funding accounted for a greater proportion of Gross National Income (GNI).

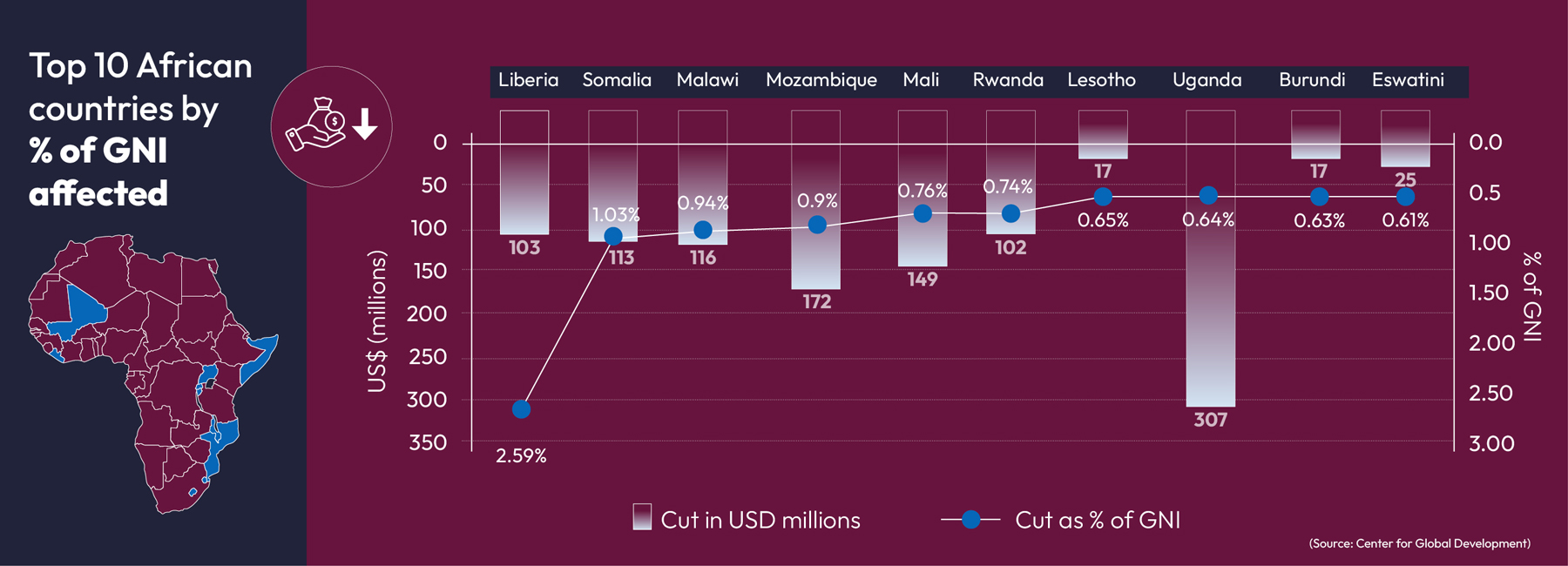

Reframing the data to examine those countries most affected in terms of USAID funding as a proportion of GNI shows that the impact is most acute in smaller and less diversified economies. This includes Liberia, Somalia – as well as Malawi and Mozambique, highlighted in the first chart.

Figure 2

(Source: Center for Global Development)

Emergency response

Some governments have been better placed to respond than others, with Somalia and Mali having limited bandwidth as the state contends with sustained conflicts.

With the USAID cuts representing a whopping 2.59% of its GNI, Liberia experienced the greatest loss in proportional terms – particularly galling on account of the country’s historical ties with the US. In an attempt to mitigate the fallout, the Liberian senate sought to reassess the country’s budgetary framework and review immediate spending priorities, with the Ministry of Health allocating USD 300,000 for commodity distribution and reassigning staff on its payroll to HIV services.

Malawi convened a country-level task team to identify mitigation measures, and sought to develop a plan for HIV commodities warehousing and distribution. International partners, including UNAIDS, have been critical in sustaining the country’s response.

However, beyond these examples, governments have been notably silent in terms of their responses, with limited publicly information available for the affected countries listed in Figure 2, beyond vague assurances of “assessing impact” and “mobilising resources”.

Rhetoric vs reality

With several African nations having (rightfully) been critical of the various antics of present and past US administrations, as well as the global aid paradigm, it would be an embarrassment to admit to the extent of their health system’s dependence on US contributions. Even more painful to admit, as in the case of South Africa, that such dependence can be attributed to domestic mismanagement and corruption within the sector, rather than a lack of internal resources.

There were a few brave and errant voices, however. Zambia’s President Hakainde Hichilema described the cuts as a “long overdue” wake-up call, although he did not downplay the anticipated impact and disruption. President of Rwanda Paul Kagame expressed similar sentiments, claiming that the continent cannot “rely on the generosity of others forever”. Despite his country having been a major recipient of donor largesse over the years, Kagame noted: “I think from being hurt, we might learn some lessons.”

With African leaders long having preached the rhetoric of self-sufficiency, now is the time to put such pithy phrases into practice. In an ideal world, governments might have been able to prepare for a more benevolent tapering off of ODA, rather than the cold-turkey approach taken by the American administration. In the words of World Health Organisation Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, while it is absolutely the right of the US to withdraw aid as it sees fit, such a process needs to be done in an “in an orderly and humane way” which gives beneficiaries sufficient time to source alternate funding.

The reality on the ground – as reported by the news media – paints a very different picture to governments’ studiously maintained countenance of calm. South Africa’s Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi was forced to confirm that the country’s HIV/AIDS programme was not at risk of collapsing, after claims to the contrary by a leading clinician. In the last two months, NPR profiled Zambians who have lost access to their lifesaving medication and their devastating descent into illness, while Associated Press reported on malnutrition deaths in Nigeria. Similar such stories can be found for many other African countries.

Where to from here?

Some beneficiaries may have been relying on philanthropic foundations to fill the gap. While such organisations have certainly been working overtime to apply stop-gap solutions, global philanthropy is facing its own funding pressures to fill the gap left by USAID alongside reductions in ODA from other major donors, including the UK, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Moreover, foundations have designed catalytic interventions tailored to achieving discrete missions, and it is unrealistic to expect them to plug gaps in other sectors.

International platforms such as the Global Fund and GAVI have themselves been affected by the cuts. The Global Fund has been forced to trim USD 1.43 billion in funding already allocated for its current funding cycle from 2023-2025, with donors failing to meet their pledged commitments. This has led to reduced country allocations, ranging from a 5% cut in South Sudan to 16% in South Africa. Gavi faces a similar predicament: while it secured more than USD 9 billion towards a target budget of USD 11.9 billion in June 2025 for the 2026-2030 period, US Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. indicated the US will no longer be contributing to the organisation.

While news this month of the US House and Senate restoring USD 400 million to PEPFAR is welcome, it should be viewed only as a temporary reprieve, with the whims of the current US administration ever-changing.

Ultimately, six months on from the emergency hustling to concoct some semblance of plans, there does not appear to have been significant progress in developing and implementing longer term solutions – at either the national and continental level. Amid plenty of talk of domestic resource mobilisation, public-private partnerships, expenditure rationalisation, diversified funding sources, innovative financing models and localisation strategies, there is a glaring lack of detail around the practicalities. Such collaborations understandably take time, but this is time that HIV-patients in particular simply do not have – particularly as stock piles of essential medications are set to deplete around mid-year.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more