We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

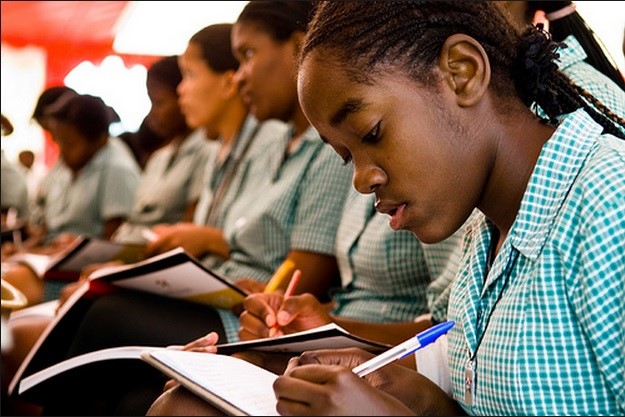

Putting learning on the agenda: Literacy and numeracy as 21st century skills

Basic reading, writing and mathematical skills are the building blocks for a productive life. Children who do not learn to read and understand a simple sentence by the age of ten, are unlikely to develop the skills necessary for later learning, or to continue their studies and fulfil their potential in inclusive and cohesive societies. These foundational skills are necessary to develop other higher-order cognitive skills in high demand, such as communication, problem-solving, and information analysis.

Globally, education is in crisis because globally students’ progress in learning has been drastically eroded by school closures occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, the proportion of ten-year olds in low- and middle-income countries who could not read a simple story is estimated to have grown from about 50% to over 70%, according to estimates by the World Bank and UNICEF. This generation of students risk losing USD 17 trillion in lifetime earnings as a result of the associated learning losses, as a result.

However, the issues affecting learning precede the pandemic. In 2019, the learning poverty rate was already estimated at 57% in low- and middle-income countries, while in sub-Saharan Africa it was 86%. Such high levels of learning poverty signal that many education systems struggle to deliver quality learning, despite – or perhaps because of – progress in improving access education.

The compounded effects of learning losses

Learning poverty is dire in sub-Saharan-Africa where one in five primary school-age children are out of school; only two in three children in the region complete primary school by age 15, and among those who do, only 3 in 10 will have achieved the minimum proficiency level in reading. This means that barely one in five children that complete primary school attain minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. These early learning problems compound to affect latter learning and productivity.

Available results indicate that between 60-75% of the workforce do not achieve minimum proficiency in foundational literacy skills even in lower-middle income countries such as Ghana and Kenya. This means they do not have a basic sight vocabulary and cannot read short texts on familiar topics to locate a single piece of information. In Ethiopia, the effects of a poor education system culminated in January when results from the national grade 12 school leavers examination revealed mass failure – only 3.3% of students who took the exam passed. Such mass failure undermines the pool of school leavers qualified to enter university, which are at 23% of admission capacity. This contributed to the government’s decision to update the existing Education and Training policy, which had been in place since 1994.

Sector stakeholders and decision-makers have raised the alarm on the need to reform education systems to secure children’s futures and countries’ economic prospects. At the Transforming Education Summit (TES) in September 2022, global leaders coalesced around the need for drastic change in education systems to adapt to the evolving world and institutionalise resilience to pervasive emergency conditions. Twenty-five countries, including the UK and the US, agreed to long-term systemic changes in areas including teaching, curriculum and assessment, and digital learning, and endorsed an international commitment to action to address the global foundational learning crisis.

Political will to improve learning is on the rise

At the end of the TES, the Presidents of Nigeria, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Guinea Bissau, Kenya and Mali all committed to instituting bold national agendas to transform education systems. Some governments have since moved to implement policies aimed at improving outcomes and curbing learning poverty.

Malawi has initiated a five-strand foundational education strategy to reduce learning poverty from 87% to 21% and ensure that 80% of Standard 4 learners can read with meaning by 2030. The country plans to: provide relevant support to teachers of Grades 1-4; improve training and deployment of teachers; redesign the curriculum and improve its resourcing; expand school feeding coverage to all schools; and digitalise education for access.

Others have taken a more phased approach. Nigeria has approved a revised national policy to encourage the use of local languages for instruction in primary schools, and has stated plans to develop a policy framework that will guide practitioners integration of methodology to improve foundational learning outcomes across the country. The government has also moved to domesticate and scale up some of the foundational learning programs implemented by partners such as UNICEF and USAID in Northern Nigeria.

African countries are increasingly coming to terms with the challenge of poor foundational learning and want to take action on it. Governments are keen to improve children’s learning at scale and are beginning to institute pedagogical methods proven to impart foundational skills in critical educational inputs such as curriculums, teacher training and assessment-informed instruction – focal channels for quality education delivery.

However, these efforts must also include the provision of the minimal conditions which improve student’s participation and learning, such as school meals and textbooks. Despite high-level commitments to boosting literacy and numeracy outcomes, a majority of governments in Africa have no national reading and numeracy plans and, significantly, no related national budget items.

Accelerating progress in learning requires both political and financial prioritisation. Local and international partners in the education sector have mobilised to support government delivery of learning in this period of increased political salience on foundational literacy and numeracy skills. There is a need for more inclusive input into the development of national plans on reading and numeracy to give education a clear intent and transform outcomes. For donors and development partners, it is an opportune moment to redirect resources to support institution building and systemic change, as currently, around 40% of development aid to the region is spent on basic education but often supports short-term projects.

At this critical juncture, all stakeholders must converge to transform education outcomes and secure the future of a generation of students unfairly disadvantaged by crises and emergencies, because learning changes everything.

About the author

Gbope Onigbanjo is a consultant at Africa Practice, she can be contacted at [email protected].

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more