We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

COVID-19 through the gender lens

The social and economic fallout from COVID-19 is gendered. Spikes in gender-based (and domestic) violence have been widely documented, as have been women’s colossal losses of livelihood in the informal economy. Women remain over represented in low-skilled work, while the pay gap has anything but disappeared. With the closure of schools and childcare facilities across the country, girls’ already constrained access to education evaporates, while mothers’ household and emotional labour responsibilities soar. Meanwhile, families seeking to save money are more likely to withdraw girls from school than boys, imposing a long-term effect on girls’ earnings.

With over 60% of Africa’s health and social care workforce being female, women face disproportionate health risks. As healthcare services clients, women are also affected negatively. The numbers of miscarriages, stillbirths and neonatal deaths are increasing as pregnant women fear seeking medical care or are simply denied it – there are reports of Kenyan women in labour not being admitted to hospital in observance of the 19:00-05:00 curfew.

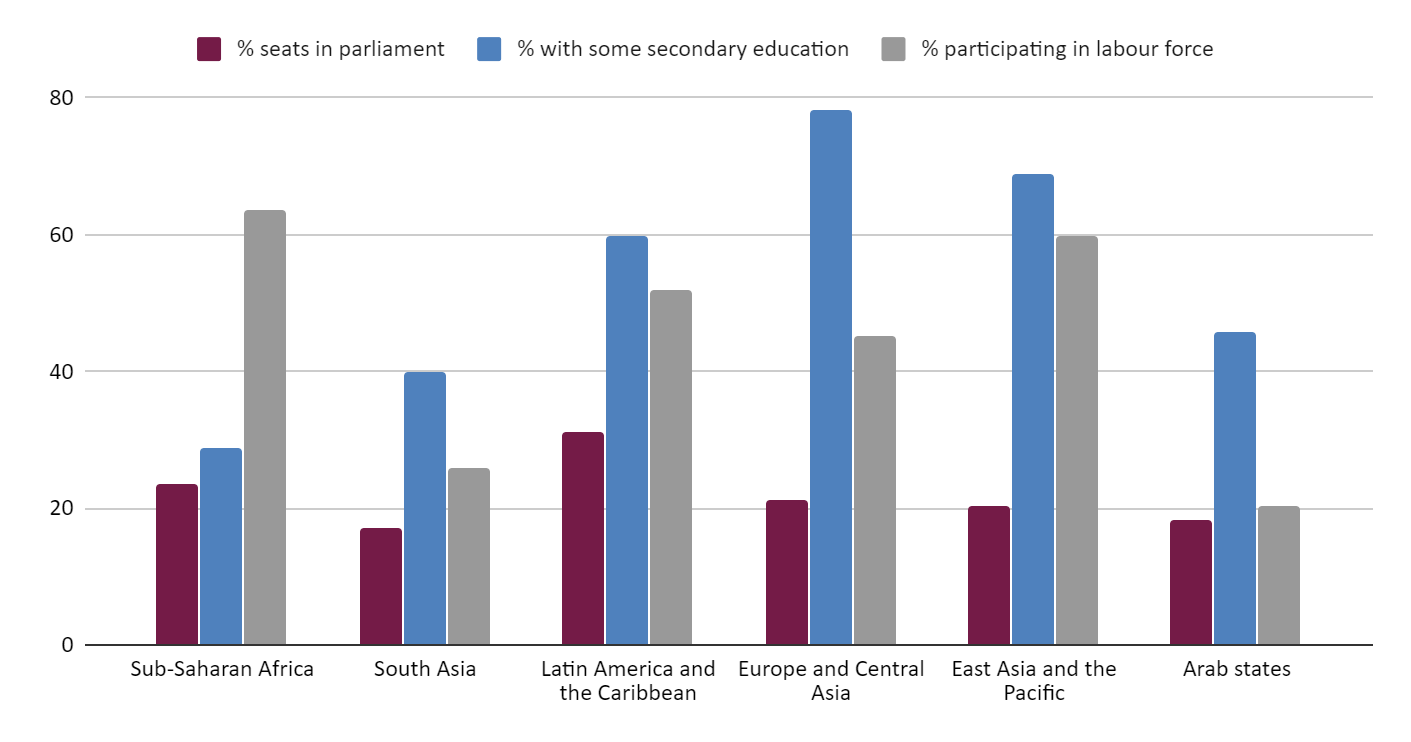

What some of the analyses of the impact of COVID-19 on women in Africa are missing is an acknowledgement that the pandemic is simply unveiling deep existing inequalities and hierarchies. None of the issues highlighted above, among many others, are new. Neither is the fact that the inequality experienced by women in sub-Saharan Africa is more acute than elsewhere. It is the region with the highest gender inequality index (0.57, more than double that in Europe and Central Asia), according to UNDP. While women constitute over 60% of the labour force on the continent – more than anywhere else in the world – they have the most limited access to secondary education.

(C) Africa Practice

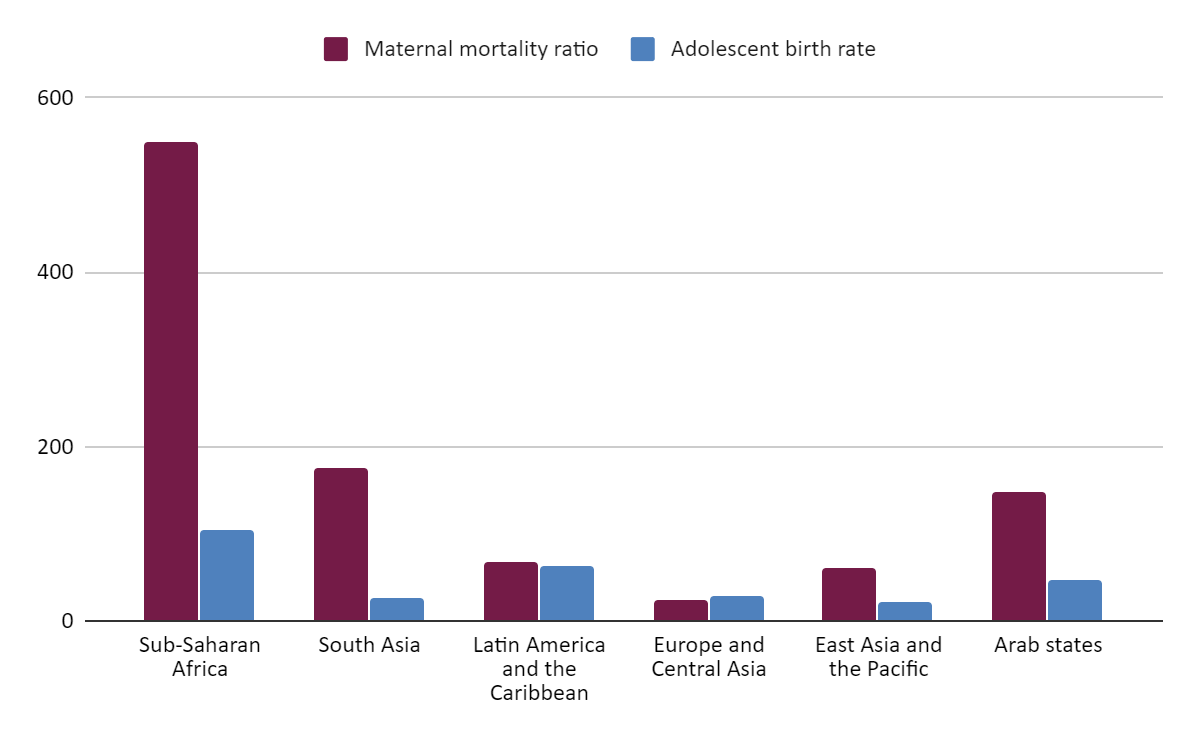

In terms of access to healthcare, and maternal services in particular, African women and girls on the continent are beyond disadvantaged.

(C) Africa Practice

Girls’ and women’s experiences of inequality and marginalisation are often homogenised or reduced to just one of the many other challenges human development is facing. Out of the 17 SDGs, only one explicitly mentions gender – “gender equality.” It is separate to the grander-sounding “reduced inequalities.” While this in itself is not an issue, shoehorning gender inequality into a separate set of development problems – rather than using it as a lens through which we examine all of them – is. In an ideal world, especially in developing contexts, a gender equality consideration would underlie all policy discussions and overlay the understanding of all development challenges. Intersecting the impact of COVID-19 on women with their positioning in terms of class, age, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and urban/rural location would be a useful first step in applying the gender lens more broadly.

Meanwhile, the diversity of African women’s experiences, including during the COVID-19 crisis, is overlooked. Adopting a gender lens to examining the pandemic’s deep impact across the continent – and not letting go of it when addressing other public health, socio-economic and political problems – is vital. Beyond this, the COVID-19 crisis should force us to reassess how we value and pay for women’s contributions to politics, society and the economy. It should also provide momentum for increasing female representation at all levels of decision-making. Equality is the surest means we know to prosperity and sustainability.

Authored by Margarita Dimova, Head of Intelligence and Analysis at Africa Practice.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more