We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Mali: Keïta between a rock and a hard place

Since early June, Mali has been embroiled in a deepening political crisis, which has brought public administration to a standstill and risks plunging the country into prolonged chaos. Marginalised communities and opposition parties across the country are denouncing the government’s failure to address long-standing security, social and political issues and calling for systematic government reform, including the resignation of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta. The crisis is severely undermining the government’s ability to combat the urgent threats of COVID-19 and an ongoing Islamist militancy.

Source: Reuters

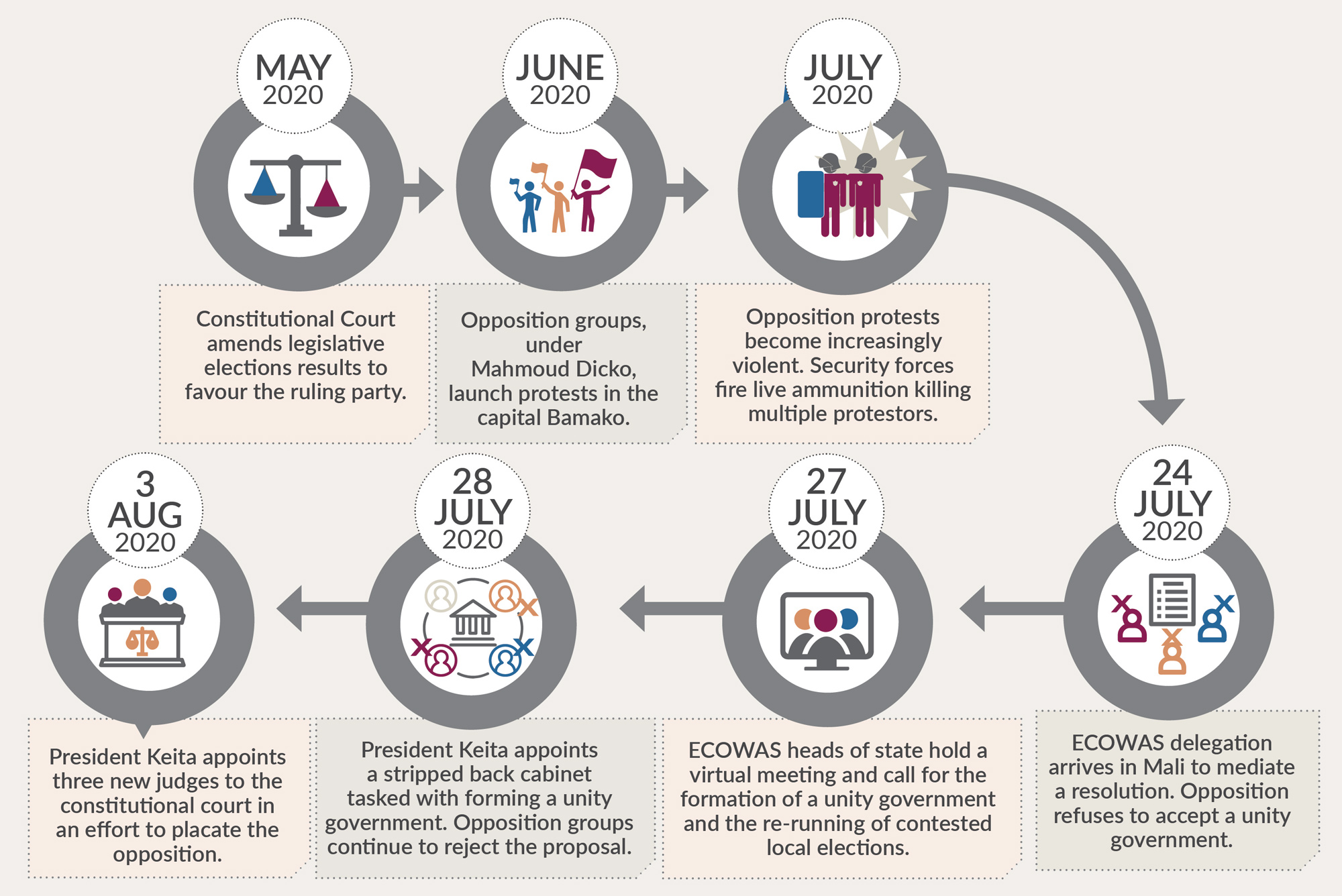

The opposition – which has coalesced under the somewhat amorphous June 5 Movement-Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP) – is steadfastly rejecting all mediation efforts by ECOWAS. Meanwhile, prominent imam Mahmoud Dicko has emerged as the anti-government mouthpiece, as Keïta continues to make concessions – including dissolving the Constitutional Court and appointing a stripped back cabinet with a mandate to form a unity government. The new cabinet, which contains several opposition-aligned appointees, suggests he is prepared to compromise further.

Source: (c) Africa Practice

Long-standing grievances come to the fore

The current crisis is reflective of long-standing grievances held by communities across the country. Since 2012, Mali has been struggling to contain an Islamist insurgency in the North, which is now spreading to the centre of the country and fuelling intercommunal violence. A 2015 Peace Accord signed with rebel groups has been poorly implemented, with armed groups continuing to launch regular attacks and security forces engaging in well-documented abuses against militants and civilians alike.

This threat has been compounded by the state’s failure to provide basic services in remote regions and by persistently high levels of poverty, despite robust GDP growth. The final straw came in May 2020 when the Constitutional Court amended the results of legislative elections, boosting the ruling party’s parliamentary majority. This has mobilised opposition parties who fear further interventions in the 2023 presidential elections.

Dicko has succeeded in positioning himself as a champion for marginalised communities and as a viable political alternative to Keïta. Despite being a well-known Islamic leader, his rise to prominence transcends religion. As young Malians have grown increasingly tired of the political elite, Dicko has emerged as an enlightened political outsider challenging the status quo. His ability to influence high-level politics, however, should not be underestimated. In April 2019, when the government decided to limit the authority of the High Islamic Council, Dicko led protests which eventually convinced Keïta to dismiss Prime Minister Soumeylou Boubèye Maïga.

Limited progress through mediation

ECOWAS has taken a leading role in mediating the crisis. Keen to uphold its reputation as an enforcer of democratic values in the region and to avoid a dangerous precedent, ECOWAS has rejected calls for Keïta’s forced removal. It has instead urged the formation of a national unity government, the re-running of disputed legislative elections, the resignation of 31 MPs whose elections are contested, and the holding of an enquiry into security forces’ abuses against protestors. On 27 July, ECOWAS hosted a virtual meeting of heads of state and reinforced these demands, while threatening strict sanctions against anyone who impeded the democratic process. The credibility of these sanctions remains questionable; figures within the opposition and the government are growing frustrated with ECOWAS, which they perceive as meddling in a fight it does not understand.

Mali’s geographic positioning makes it of high strategic importance to regional and international partners. The landlocked country shares permeable borders with seven neighbours, all of whom are currently suffering their own domestic security crises and are becoming increasingly cognisant of the exportability of Mali’s Islamist insurgencies. Political turmoil in Mali could create fertile ground for these groups to expand within the broader region. International observers are also keen to preserve Mali’s secular constitution and to prevent Dicko, who holds traditional Islamic views on sexual health and family matters, from assuming a position of political power.

Relative economic stability amid COVID-19, so far

This political crisis takes place against the backdrop of COVID-19 and rising economic uncertainty. The impact of the virus on Mali’s economy to date has been limited. As a net importer of oil, the country has benefitted from the global oil price slump, as well as the stable price of its own main export – gold.

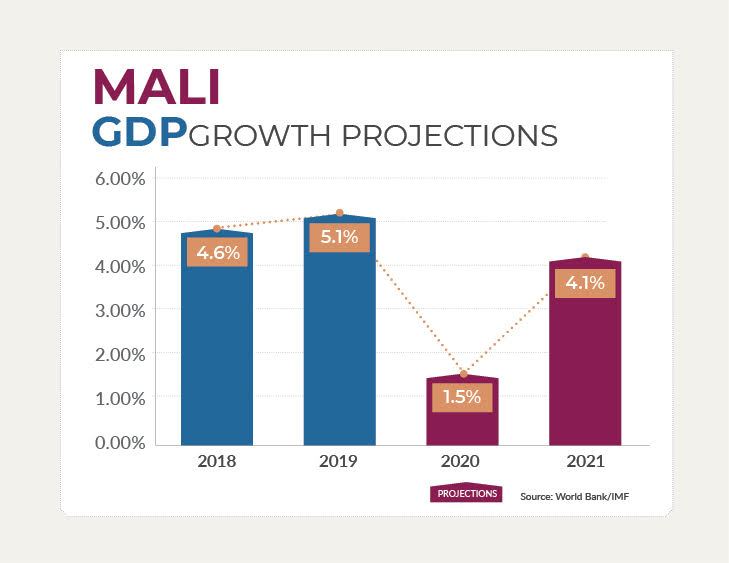

While these factors provide an effective economic buffer, the IMF predicts that a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases and a further downturn in the global economy could see Mali experience GDP growth of 1.5% in 2020, compared to 5.1% in 2019. The agriculture sector, which employs over 80% of the workforce, is set to suffer significantly in the event of a prolonged downturn in trade. Mali’s main agricultural export, cotton, has seen a 25% reduction in value since March 2020, leaving millions of farmers out of pocket.

Mali does have adequate fiscal space to enact socio-economic mitigation policies, and recently has sought to lower the price of key agricultural inputs. However, implementation of these measures will be difficult while the government remains in hibernation and political capital is diverted towards the current deadlock.

Source: World Bank/ IMF

No resolution in sight

Keïta’s concessions are failing to resolve the deadlock. The opposition continues to reject the prospect of a unity government, which they fear would allow the president to neutralise his political opponents. There is also little desire within government to allow a rerun of the legislative elections, as this would likely jeopardise the parliamentary majority that Keïta’s party has, and hinder his decision-making power ahead of the 2023 election. ECOWAS’ recommendations have thus only served to fuel political tensions.

The majority of opposition leaders have now accepted that Keïta must fulfil the remainder of his mandate. They are thus calling for further concessions – the appointment of a new, consensual prime minister, the limiting of presidential powers and profound electoral reform. Meaningful progress will only be made if Keïta is willing to open a constructive dialogue and relinquish his stranglehold over the political apparatus.

About the author:

Tristan Puri is a Consultant at Africa Practice specialising in francophone West Africa. He can be contacted at [email protected]

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more