We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

What went wrong?

Dressed head to toe in white, an octogenarian is stiffly punching the air as part of a surreal electoral campaign dance. This is Guinean President Alpha Condé, failing to recognise the tune to his own country’s national anthem, until he is reminded by a member of his entourage and the dancing stops.

Alpha Condé mistakenly dancing to Guinea’s national anthem during a rally

Source: Gist of the Day

Two weeks after this incident, Condé was re-elected for another (controversial) term, having already been in power for a decade. The polls were marred by pre-electoral violence and severe criticism by the opposition. In stark contrast to the current situation, in 2010 Condé assumed office as Guinea’s first freely elected president, pledging to strengthen the country’s democratic credentials. “What went wrong?” many are asking.

Electoral febrility across the continent

Unfortunately, the Guinean polls are not an outlier scenario on the continent’s electoral calendar this year, even this past month.

In Tanzania, on 1 November, President John Magufuli was formally re-elected, securing a resounding victory with 84% of the votes. Amid international outcry and condemnation of the freedom and fairness of the electoral process, a number of opposition leaders were arrested, while internet restrictions continue to disrupt the lives of ordinary Tanzanians to this date. Meanwhile, the ideology and publicity secretary of the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), Humphrey Polepople told Financial Times that while content with its victory, the party, in power continuously since independence, was actually aiming for 95%.

In Côte d’Ivoire, the elections went ahead as planned on 31 October even though the opposition boycotted them. Today, the official results saw President Alassane Ouattara re-elected for a third term with a staggering 94.27% of the votes – not far off Magufuli’s ambitious goal in Tanzania. In 2016, Côte d’Ivoire adopted a new constitution that limits presidents to two terms in office; it did not specify whether this would be applied retroactively, opening the door for another Ouattara term. Although he initially refused to run, a predictable U-turn followed.

The recent electoral outcomes across the continent point to what has already been dubbed the reversal of Africa’s democratisation process. “Many countries in Africa are falling short in their efforts to consolidate constitutional rule, in respect of presidential term limits […] laws on elections, civic space and political party activity,” Cameroonian academic Christopher posited in a September submission to the US Congress Foreign Affairs Committee. Applying such a sweeping theory of regression could obscure some of the idiosyncratic, and not so idiosyncratic, country dynamics producing the concerning outcomes we are witnessing.

Big men, small horizons and toxic masculinity

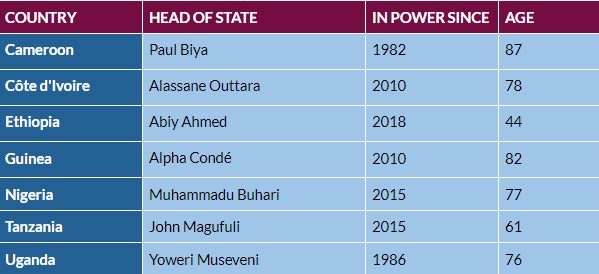

Condé, Ouattara and Magufuli would all qualify as the archetypal “big men” that still dominate political life in many African countries. But a monolithic category of “African big men” can be problematic and misleading; these three men are not all the same. At 61, Magufuli is relatively young, but displays perhaps the most restricted of worldviews. Ouattara was ready to hand over power to his successor, Prime Minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly, before the latter died from heart failure in July. In the meantime, other “big men” archetypes – Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, 76, and his Cameroonian counterpart, Paul Biya, 87 – are veering towards derision, even if they have proven uncompromising when the electoral cycle heats up. Case in point is yet another violent arrest of Uganda’s youthful opposition leader Bobi Wine, which took place today.

(C) Africa Practice

It is difficult to ignore the fact that all of these entrenched political figures are men. It is equally easy to attribute their fixation with holding onto power to a single notion of a patriarchal dominance or toxic masculinity. They are either members of vast political dynasties, or deeply enmeshed in high-stake, overlapping business and other vested interests. Disentangling oneself from such complex networks is neither easy, nor safe.

But their positions of power are also alluring because of their highly symbolic nature, invariably intertwined with machismo, bravado, and dominance. Complying with a textbook patriarchical imagery, Magufuli has publicly done push-ups on a number of separate occasions, as has Museveni and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Coupled with an often blind reverence for age as an automatic signifier of authority, these patterns are producing and reproducing deeply damaging trends and narratives across political generations.

John Magufuli performing push-ups at a political rally

Source: The Citizen

Ending the politics of gerontocracy

The #EndSars protests in Nigeria illustrate the deep inter-generational tensions that need prompt resolution in many African political contexts, regardless of the actual age of the head of state (Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari, for the record, is 77 years old). This disturbing, bloody episode in Nigeria’s history could serve as a much-needed rupture with the past, bringing younger, more diverse political actors onto the stage. “What next? Where do we go from here?” asked the moderator of the post-protest Zoom session held among the movement’s leaders. Responding, musician, activist and lawyer Folarin Falana (aka Falz), confidently stated: “I dare say things will never be the same in Nigeria again.”

An #EndSars protestor holding a sign

Source: Getty Images

In a year marked by such profound levels of uncertainty, things will never be the same again everywhere in the world. The precarious situations in Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea and Tanzania, among others, are proving that the democratisation process across Africa can be a non-linear one. In the aftermath of some of the disconcerting electoral events outlined above, there should remain space for challenging authority, demanding accountability and participating in genuine political dialogue. Otherwise, violence and turmoil will remain the only tools available.

About the author:

Dr Margarita Dimova is the head of Intelligence and Analysis at Africa Practice, based out of Nairobi.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more