We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

What priorities for African countries at COP26?

Although a low contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, Africa is predicted to be the continent worst affected by climate change, along with small island states.

Rising global temperatures are already having a pronounced impact on livelihoods and threatening ecosystems and development gains – for instance exacerbating drought and desertification in the Sahel, and inducing a major ongoing famine in southern Madagascar. According to an October report by the World Meteorological Organization, AU Commission and UNECA Africa Climate Policy Centre, up to 118 million extremely poor people on the continent will be exposed to drought, floods, and extreme heat by 2030. The 2021 Global Climate Risks Index found that five of the ten countries most at risk from climate change were located in sub-Saharan Africa, with Mozambique and Zimbabwe in first and second place.

As global emissions continue to rise, the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) – which opens in Glasgow on 31 October – comes at a critical juncture for African countries. Amid growing calls for urgent action, driven by the latest warnings from the IPCC, the conference will serve as a barometer of how the international community intends to share the burden of reducing global emissions. While much of the negotiations will revolve around technical details and rules to implement agreed emissions reductions, African delegates will collectively and individually be pushing an agenda that reflects the disparities between developing and more advanced economies.

More ambitious emissions commitments

Perhaps the most important negotiating point for African countries is to press for more ambitious emissions reduction targets from high-emitting, wealthier economies. This is aligned with the crux of the COP26 negotiations — to keep alive the 2015 Paris Agreement and maintain global temperatures well below 2°C (preferably within 1.5°C) of pre-industrial levels — in order to avert the consequences of unabated global warming. Present emissions reduction commitments are insufficient to meet that goal in time and it is beyond most developing countries to bridge that gap. Today, while home to some 17% of the world population, the contribution of Africa to global carbon emissions is approximately just 3%, with a small number of countries accounting for a substantial proportion of these emissions.

Increased climate finance and accountability

Formal negotiations will begin at COP26 on a post-2025 climate finance goal. Some countries have already given indications of how much financial support they believe will be needed for climate goals to be met. In July this year, South Africa Minister of Environment Barbary Creecy put the figure at USD 750 billion annually after 2025. Though a target is unlikely to be agreed in Glasgow, a commitment to a substantial increase from the current target — USD 100 billion per year — would be a positive outcome.

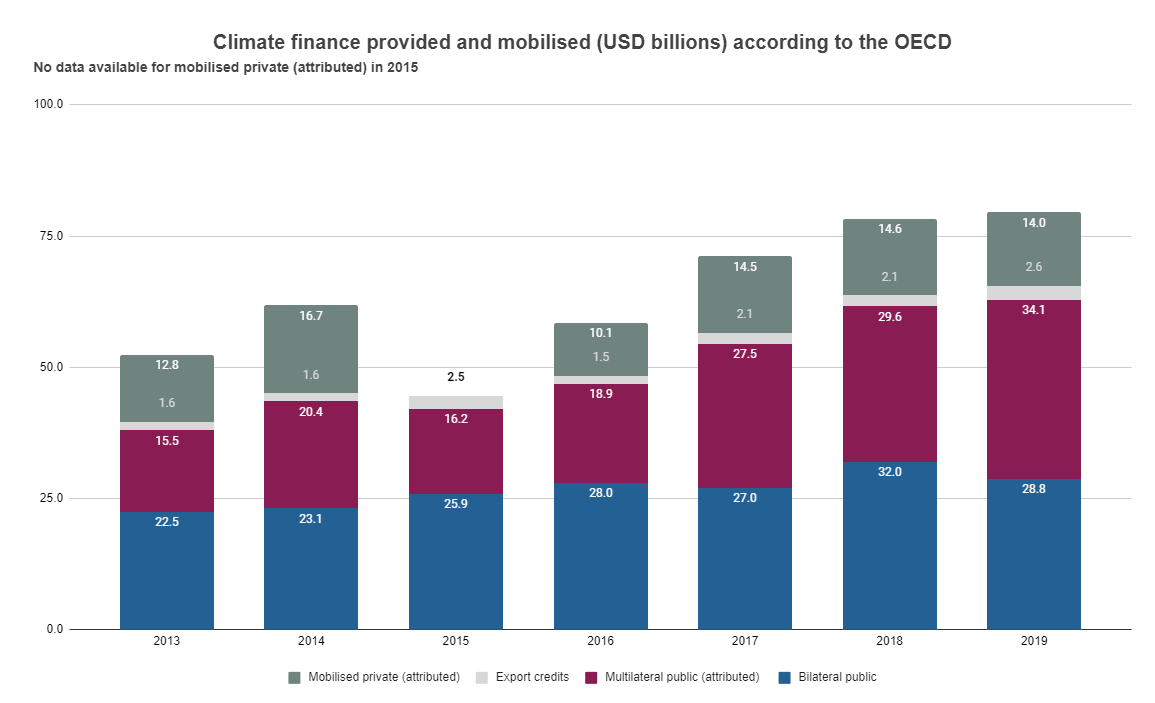

Progress is not only needed in terms of overall commitments, but on implementation and accountability. Developed countries have failed to meet their pledge of mobilising USD 100 billion annually in climate finance by 2020 in support of developing economies, as illustrated in the graph below. On 25 October, the UK COP26 Presidency published a plan expressing confidence the target would be met by 2023 and exceeded thereafter up to 2025.

In response to these missed commitments, the chairperson of the African Group of Negotiators on Climate Change, who will represent the continent’s collective interests at the conference, suggested that African countries will be negotiating for a new system to track funding pledges. A failure to do so would risk exacerbating frustrations over broken promises, as well as complicating these and future climate negotiations.

Incentives for a clean energy transition and protecting nature

It is crucial that COP26 and present and future climate finance address some of the unique circumstances and needs of the continent. For instance, the African population is expected to rise from 1.3 billion to 3 billion by 2060, which will put pressure on emissions targets in different ways. In terms of energy access, the situation in sub-Saharan Africa is a major brake on development, with the region home to 75% of the global population without access to electricity – equivalent to approximately 600 million people. To address these challenges, it will be key to:

- Scale financial and policy support for renewable energy while acknowledging the transitional role of natural gas to address energy access and minimising the associated emissions. Renewables adoption is accelerating yet remains hampered by intermittency and financial and feasibility constraints. Until renewables are scaled and reliable enough, the development of natural gas, reserves of which in Africa are estimated at 600 trillion cubic feet, will be necessary to alleviate the crushing energy deficit on the continent.

- Guarantee more financial incentives and support to preserve those of their natural resources which act as major global carbon sinks. Congo Basin nations in particular, such as the DRC, Republic of Congo and Gabon, are pushing for a fairer and fuller valuation of the contribution of their forests to global climate change mitigation.

Additional funding for adaptation

African negotiators and delegates have also been pushing for a more even split between mitigation and adaptation. The AfDB and Global Centre for Adaptation will look to secure increased allocations to the Africa Adaptation Acceleration Programme (AAAP), which has received broad backing from African leaders, development partners and international organisations. In its COP26 manifesto, the Climate Vulnerable Forum, which includes 17 African countries, also called for more engagement behind the AAAP and for a fifty-fifty split of climate finance between mitigation and adaptation.

At present, mitigation accounts for some two-thirds of climate finance provided by developed countries, driven by financing for the energy and transport sectors. While mitigation is ultimately the key for emissions reductions, Africa is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change – such as climate-related natural disasters and food insecurity – and there is broad consensus that financing adaptation makes more economic sense in the long-term than frequent disaster relief.

The cost of adaptation is substantial, estimated by the IMF to be between USD 30 and 50 billion annually up to 2030 for Sub-Saharan Africa alone. But it also constitutes a major source of potential growth and a huge investment opportunity, including in climate-smart infrastructure and agriculture, which will require the rapid mobilisation of both public and private finance.

Negotiations at COP26 are expected to be more challenging than in Paris in 2015 and may not lead to the urgent action being called for globally. A recognition of the unique set of circumstances faced by Africa, where climate change is already affecting development and livelihoods, is a major desired outcome.

About the author

Alex Vergé is an Associate Consultant at Africa Practice. He can be contacted at [email protected]

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more