We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Drought in the Horn of Africa: A neglected crisis?

The Horn of Africa’s worst drought in four decades has seen over 16 million people in the region at risk of extreme food insecurity, with this projected to rise to 20 million by September. This comes as a record fifth consecutive rainy season looks set to fail – an extreme meteorological event worsened by multiple geopolitical and economic factors. These include increasing food and fuel prices as a result of the war in Ukraine and its impact on global supply chains, strained public finances weakening national governments’ capacity to respond, and a significant shortfall in donor requests for assistance.

A range of competing domestic priorities have fuelled criticism that addressing this humanitarian emergency has taken a backseat. Ongoing attempts at conflict resolution in northern Ethiopia, upcoming elections in Kenya and insecurity and a protracted election period in Somalia have all taken up significant political capital and detracted from response efforts.

Assessing the scale of the challenge

The scale of impact in each of the three main affected countries are stark. In southern and southeastern Ethiopia, 7.8 million people are in need of emergency food assistance, joining the 9.8 million people across the northern Ethiopia regions of Tigray, Amhara and Afar that require humanitarian assistance as a result of conflict. Continued international attention remains focused on northern Ethiopia, particularly on humanitarian access to Tigray and prospects for negotiations between the federal government and Tigrayan forces, which are slowly improving. This has even been explicitly stated by key regional officials, including the president of the worst-affected Somali regional state, Mustafa Mohammed Omar, who argue that the attention of international donors and the federal government remains “caught up” in northern Ethiopia.

While Ethiopia has tried to drive its own response – through expanding the coverage of its Productive Safety Net Programme from the 8 million it was already serving to the 3.5 million food-insecure Ethiopians affected by the conflict in the North – its efforts are reaching fewer than the total number of Ethiopians affected by the combination of drought and conflict.

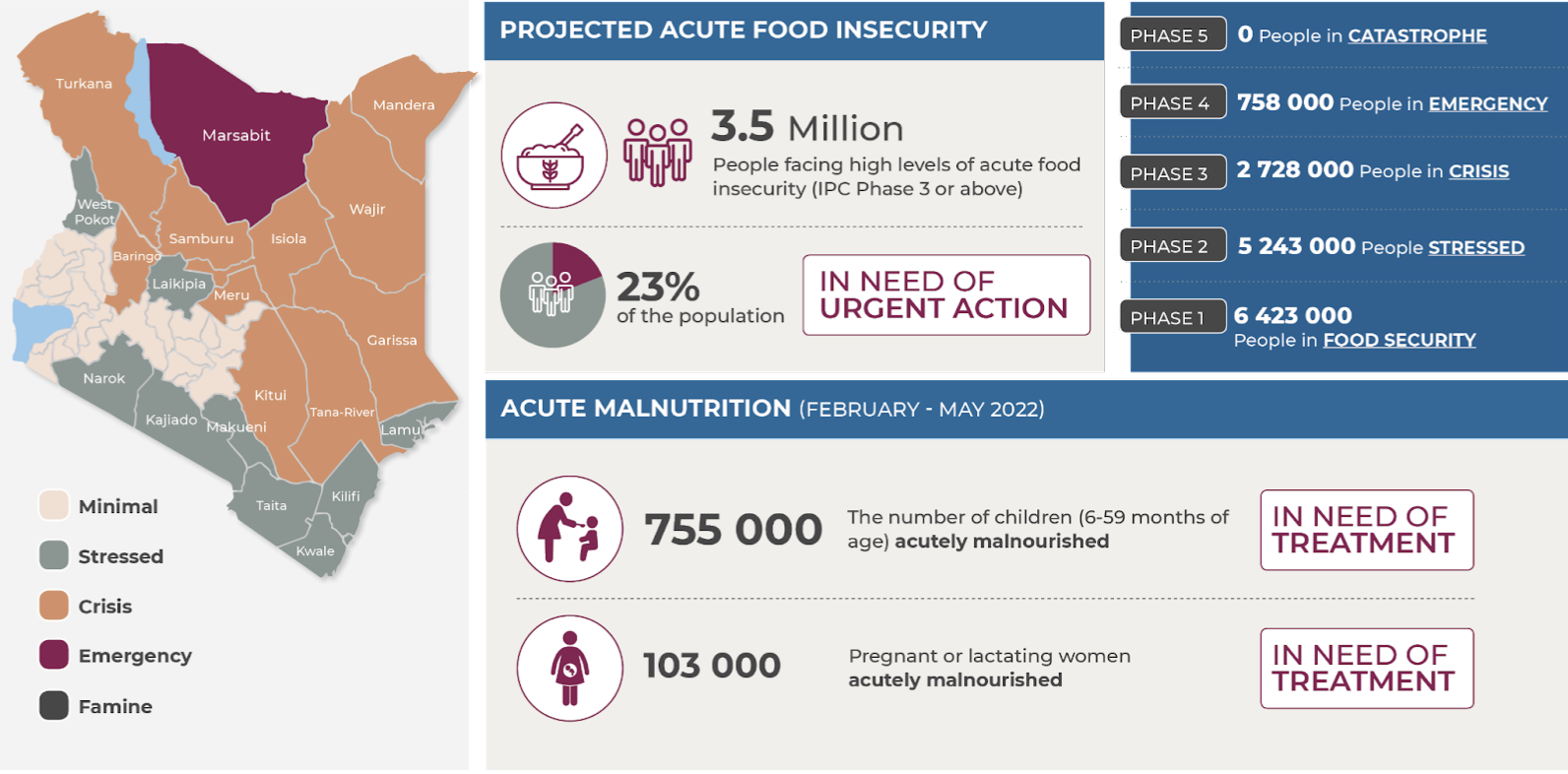

With 4.2 million people in Kenya at risk of hunger, and over 1 million livestock having perished, the Kenyan government has continued various attempts to support affected populations. For example, the government has promised to continue disbursing KES 5,400 (USD 46) per month to 108,000 poor and vulnerable households in drought prone areas every two months as regular cash transfers.

Despite such initiatives, domestic political attention is almost entirely focused on the closely contested August elections, meaning that an already insufficient national-level response continues to fall behind the scale of need. If the electoral process becomes a protracted one, with multiple legal challenges and a run-off, this could further slow the response.

The crisis is most acute in Somalia, where 38% of the total population are at IPC Level 3 or worse. Although the recently concluded presidential election, which saw the return of Hasan Sheikh Mohamud to Villa Somalia, brought a degree of stability, the politicking to date has meant that the emergency response has been almost entirely left to humanitarian agencies.

Addressing the response shortfall

Inadequate national responses have been compounded by insufficient donor commitments to meet the scale of need. In Somalia, the humanitarian response plan for this year is only 20% funded, while only 34% of the amount initially requested for Kenya between October 2021 and March 2022 has been met. The amount required for Kenya has further increased since April 2022, with only 19% of funding needs met to date.

With continued international donor attention on the crisis in Ukraine or as in the case of Ethiopia – on conflict affected areas in the north, the gap in funding is widening. The World Meteorological Organisation predicts that the La Niña weather pattern, which has been the driving force behind this drought since 2020, will continue well into 2023, further worsening and prolonging the humanitarian crisis across the region.

About the Author

Tewodros Sile is an associate director at Africa Practice, with a particular focus on East Africa and the Horn of Africa region. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more