We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Much ado about artificial intelligence in Africa: Getting it right

Picture AI in Africa as a new high speed train, hurtling towards tomorrow’s possibilities, seizing everyone’s intrigue. But it would be reckless to board this innovation express if there were not already sturdy tracks in place, wouldn’t it? The buzz around AI on the continent has gained steady momentum, with its potential impact on various sectors generating significant attention. However, amidst this excitement, there are important foundational concerns.

For one, AI’s effectiveness heavily relies on data, making data protection pivotal in safeguarding individuals’ privacy and ensuring ethical AI deployment. While strides have been made, such as the implementation of the Malabo Convention, a stubborn minority of African countries still lack concrete instruments for data protection. Malabo offers a continent-wide framework to harmonise data protection policies. Next, for a continent now focused on accelerating a single market vision, we still have yet to advance a shared digital humanism approach; one that considers digital rights as a given.

Continental progress on AI

In early November 2023, world leaders – including those from Kenya, Nigeria and Rwanda – met in the UK for an AI summit. They opened the meeting with the signing of the Bletchley Declaration, affirming the need for safe development of AI, given the risks it could pose, especially in the domains of daily life.

Since then, a Nigerian legislator has introduced a bill purporting to “control” AI usage, and Nigeria and 19 other countries have agreed to non-binding UK and US-led guidelines to make AI “secure by design.” Elsewhere, BRICS countries – including South Africa – have agreed to launch the AI Study Group of BRICS Institute of Future Networks.

Against the background of global advancements, the African Union (AU) is itself making steady progress towards advancing a continental narrative for AI. In August, drafters of the AU-AI continental policy framework met to prepare for its presentation to member states, scheduled for adoption at the AU Summit in February 2024. The framework’s adoption should guide both the continental and domestic approaches going forward.

The Intellectual Property protocol to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement also makes specific reference to protecting and promoting the access and use of emerging technologies – reflecting AI’s potential to drive Africa’s vision for a single trade market. We expect the AfCFTA Digital Economy protocol to determine concrete steps towards the same. Meanwhile, a regional think tank, the African Center for Economic Transformation, is designing a multi-country programme beginning in 2024, to explore specific applications of AI for economic policymaking through sandbox exercises and peer learning engagements.

AI governance arrangements for the African context

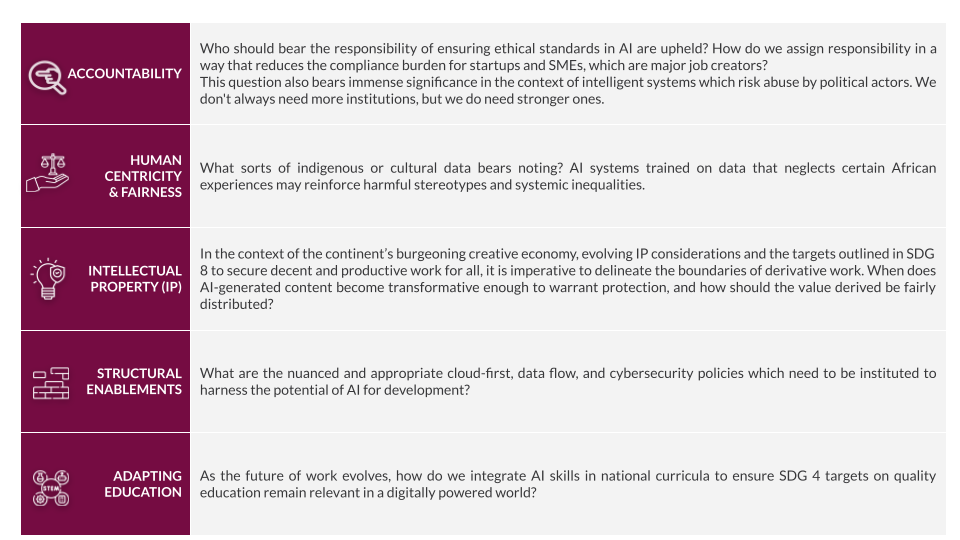

Even as efforts to align on the most significant risk-based elements are underway, there may still be key variances in the wider approach to AI governance, driven by differing cultural contexts. For instance, where the US tends to prioritise innovation, and the EU adopts a rights approach, China may advocate state control. And so, out of necessity, Africa’s cannot be a one-size-fits-all model borrowed from the global north, but a dynamic one, informed by a dual approach of risk management and opportunity generation. It should be aligned with legal and moral rules — with the continent’s priorities and cultural sensitivities at its core. Key questions thus emerge for consideration, from the perspective of both AI deployment and AI enablement:

What’s the fuss really about?

There is evidence to suggest that AI has the potential to innovate the agricultural sector, support energy reform and transition, identify and empower the most vulnerable communities and advance solutions to pressing development challenges as our digital ecosystems evolve. Estimates suggest that by 2030, 70% of global companies will integrate at least one type of AI technology, translating into a potential economic output of USD 1.2 trillion for three regions including Africa.

Yet, AI isn’t just the accelerant of future development in Africa – it’s already here! For instance, Cameroonian start-up Agrix Tech’s AI-based app supports farmers by diagnosing and suggesting remedies for infested crops. With high illiteracy rates, the app even reads the diagnosis aloud in local languages. Hello Tractor connects small-scale farmers with local tractor owners, accelerating farming operations and productivity. In Togo, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Novissi, the government’s mobile payment platform leveraged AI to identify the most vulnerable people; resulting in USD 34 million in aid reaching over 920,000 beneficiaries.

Getting it right

The benefits of AI lie in its potential and especially so for the African context – but leveraging this potential for development is contingent on aligning planning with implementation, and getting the fundamentals right. All of this planning for emerging technologies is moot if the fundamentals of the African context continue to undermine AI’s potential to be a force for SDG advancement. For instance, digital public infrastructure, connectivity in underserved regions and digital literacy remain sticking points. Crucially, data, particularly official data, is often outdated, inconveniently aggregated or else poorly collated in ways that may hinder its use in AI models. These are surmountable issues, however; African governments and partners will need to mobilise funding, muster significant political will, promote collective consciousness of the issues and advance institutional reform across governance structures on the continent.

The UN has since recognised the need for a high level, global, advisory body on AI, to advance recommendations for the international governance of AI. Treaty fatigue notwithstanding, this approach for global coordination is noteworthy, but this body must also seek to ensure that AI governance arrangements are sensitive to differing contexts. Only through inclusive AI governance can we ensure that AI becomes a powerful force for equitable progress. In the end, AI provides African nations with a promise: that technological advances can meaningfully improve our sustainable development outcomes.

About the author

Amaka Yvonne Onyemenam is a Senior Consultant at Africa Practice, advising on technology policy and regulation. She is also a Member of the Center for AI and Digital Policy (CAIDP) Research Group. She can be reached at [email protected].

Related articles

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more