We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

From sky to ground: Why Africa needs licensing harmonisation for inclusive satellite connectivity

There is a quiet but decisive frontier in Africa’s digital future, and it is not undersea cables, 5G rollouts, or even grand slogans of “smart cities”. It is the set of coordinated rules (or lack thereof) that decide who can operate satellites, on what terms, and at what cost. Without harmonised licensing frameworks, the most promising connectivity revolution of our generation risks being strangled at birth by paperwork, protectionism, and policy drift.

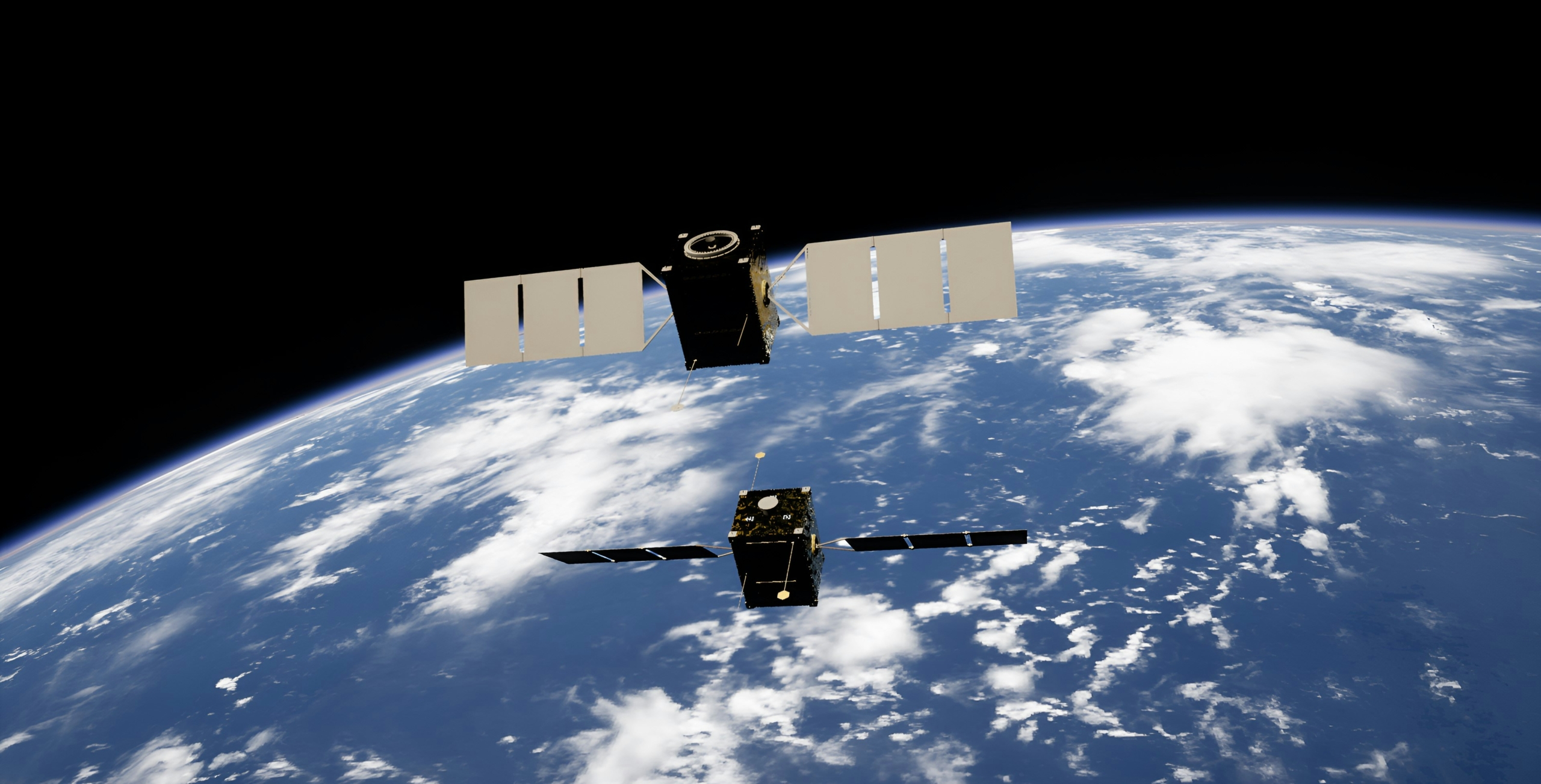

Across Africa today, satellite connectivity may be both our greatest hope for bridging the digital divide and our most underused tool. Low Earth Orbit (LEO) constellations, like Starlink and OneWeb, can beam high-speed internet to remote villages where fibre may never reach, connect rural clinics to urban hospitals, enable mobile money in last-mile markets, and backhaul data for mobile operators at lower cost than rolling out new towers. The African Union’s own Space Policy and Digital Transformation Strategy are unequivocal: space-based communications are essential for economic integration, resilience, and inclusion. But this vision may stall at the launchpad, and not because of technology, but because of licensing.

A continent of walls

Rather than a unified, rules-based market, Africa’s satellite licensing landscape is a tangle of national requirements and ad-hoc negotiations. Côte d’Ivoire explicitly denied Starlink a licence on national security grounds, while just over the border in Ghana, regulators have signalled openness to LEO services. In Central Africa, Cameroon banned Starlink in 2024, even as Angola is cautiously reforming its regime under a SADC harmonisation push. Meanwhile, Namibia has gone as far as to allow spectrum trading and granted licences within months, but neighbouring Botswana only finalised Starlink approval three weeks ago.

Some countries require individual licences for every single user terminal, making mass deployment economically impossible. Others require costly local gateways or equity stakes for foreign operators, even when such conditions have little to do with managing connectivity and everything to do with political leverage.

Fees and timelines vary widely: an application may take weeks in Lesotho, but take several years in Sudan or Burundi. In some markets, user-terminal blanket licensing is accepted and in others it is unrecognised, boxing operators into terminal-by-terminal approvals. The result is a continent of walls: invisible to the naked eye but impossible to cross at scale. Satellites do not recognise borders. When rules change from one crossing to the next, Africa loses the economies of scale that make universal access affordable.

The cost of disarray

This regulatory fragmentation exacts three distinct costs:

- Lost inclusion: In Eastern Africa, Ethiopia has cautiously piloted LEO rules, but without much public clarity. Rural schools remain offline while decisions sit in ambiguous processes.

- Lost investment: Inconsistent rules repel serious long-term capital. Global operators need predictable, harmonised licensing to commit infrastructure to Africa. Côte d’Ivoire’s outright denial and Cameroon’s ban could spook investors who need predictability. Why commit capital when access can be revoked overnight?

- Lost sovereignty: Operators play regulators against one another. Starlink secured a 10-year licence in Lesotho while still banned in Cameroon. Who holds the power in that dynamic? Without a coordinated licensing approach for non-terrestrial networks (NTNs), Africa cedes negotiating power to external players who can cherry-pick favourable jurisdictions, driving a wedge into continental integration.

When each country applies its own timelines, fees, equity rules, and infrastructure demands, the continent loses the things that are essential for competitiveness: speed, scale and certainty.

Harmonisation is infrastructure

Harmonised satellite licensing rules are as essential as the satellites themselves. Bodies like the African Telecommunications Union (ATU), Smart Africa, and ECOWAS have already taken early steps toward model frameworks, recognising the benefits of satellite for backhaul and deepening inclusion. These efforts must accelerate. We need blanket licensing for user terminals, mutual recognition of equipment type approvals, transparent and non-discriminatory landing rights, and cost-based licence fees.

At first glance, this may seem like a purely technical agenda, but it is also certainly a geopolitical one. Without harmonisation, Africa will approach the satellite era as 54 separate markets, many too small to shape the rules and vulnerable to being locked into unfavourable terms. With harmonisation, we can present a single, attractive market that invites competition, drives down consumer prices, and safeguards digital sovereignty.

Convening the conversation

There is opportunity now. LEO constellations are expanding, Earth Stations in Motion (ESIMs) are enabling on-the-move connectivity for land, sea, and air, and projects like Amazon’s Kuiper are preparing to enter the African market. Africa must decide whether it will engage these opportunities as a coordinated bloc or as disconnected fragments.

This is the first in a series that will explore the technical and political levers for a truly pan-African NTN licensing policy: unpacking the bottlenecks that slow deployment, models that work in other regions, and the diplomatic architecture needed to turn harmonisation from aspiration into operating reality. If we get licensing harmonisation right, it could be the ground station for Africa’s inclusive digital future. Space could be our next sovereignty frontier.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more