We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Africa: Trends to watch in 2024

2024 is around the corner. As we close off 2023, Africa Practice has summed up the 10 main trends to watch in 2024, across geopolitics, climate, the economy, as well as stability and security. We also revisit some of the predictions we made for 2023 and forecast the key dynamics to watch in the year ahead.

Geopolitics, climate change and the energy transition

1. A seat at the table

2023 witnessed major advances in African representation in international diplomatic and economic fora, as we predicted, with this trend set to continue. 2024 will represent a high-water mark for continental agency, as more ambitious proposals for UN Security Council reform lose momentum.

In August, the BRICS alliance was expanded to include six new members – Egypt, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Iran, and Argentina – highlighting the shifting geopolitical landscape. Although BRICS has been dismissed as a talk shop of uneven members with little common purpose, the alliance is growing stronger under Chinese leadership. The UAE and Saudi Arabia are undisputedly the two most important new member states, and with their accession, BRICS moves from a net energy-importing bloc to one responsible for 42% of the world’s oil production. The inclusion of Egypt and Ethiopia reflects the importance of these two nations to China and the Gulf.

In September, the AU became a member of the G20. This recognised that South Africa – the G20’s only other regional member – could not effectively represent the continent’s complex and multifaceted priorities. A stronger voice for the AU promises to strengthen African agency and encourage greater ambition for continental representation in major decision-making bodies. But hopes for UN Security Council reform, establishing a permanent seat for Africa, look set to remain deadlocked over the next year, as leading advocate US President Joe Biden focuses on securing re-election in November 2024. This will not stop African leaders from agitating for a seat at the table, reminding their counterparts from the US, UK, France, China and Russia at any opportunity that they have pledged to support Security Council reform.

2. Climate accountability, finally

In 2023, Africa became an increasingly vocal critic of the failures of the Global North to honour and strengthen its climate finance commitments, including promises to provide USD 100 billion annually in climate finance. In 2024 the focus needs to turn to implementation, after a series of high profile pledges at COP28.

At the inaugural Africa Climate Summit (ACS) in September, Kenya’s President William Ruto asserted his leadership on the issue, while forging a continental stance on climate finance and the necessary reforms. The Nairobi Declaration on Climate Change called for expanded and more flexible concessional funding, additional credit-enhancement and credit-guarantee schemes to incentivise private sector participation in African climate projects, and new debt relief interventions and instruments. ACS also drove home Kenya’s leadership on renewable power generation, thanks to its abundant geothermal, solar, wind and hydropower resources. Still, the African continent attracts only 3% of global energy investment. This needs to double to over USD 200 billion per year by 2030, if African countries are to achieve universal electrification and meet their nationally determined contributions.

African leaders also played a prominent role at COP28 in November. The establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund on the first day, accompanied by USD 100 million of funding from summit hosts, UAE, and a further USD 550 million from various donors, promises to provide relief for low-income countries impacted by climate disasters. However, the sum falls far short of the estimated need, and implementation remains a major concern, given the historic tendency of the Global North to over-promise and under-deliver on climate finance. Nearly two-thirds of climate finance commitments registered by the OECD between 2013-2021 – amounting to USD 343 billion total – have yet to be recorded as disbursed or are only tangentially relevant to climate, according to research by ONE.

3. Green minerals

2023 witnessed a rise in resource nationalism as African states moved to demand local beneficiation of critical minerals required for the energy transition. In 2024, we expect governments to focus their attention on the opportunities to leverage renewables and green hydrogen to power industrial-scale mineral processing.

This manifested with a series of countries designating “strategic minerals” for in-country processing in 2023. For Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Namibia and Zimbabwe, decision-making was driven by rising global demand for lithium – a key input for electric vehicle batteries – and a desire to establish local value addition opportunities and create jobs. In this vein, Zambia and DRC continue to advance their plans to establish a special economic zone for the production of battery precursors, pending the release of a pre-feasibility study conducted by ARISE Integrated Industrial Platforms.

Elsewhere, we anticipate additional efforts by the Guinean government to promote the establishment of alumina refineries to process locally-mined bauxite, as the junta prepares for transitional elections scheduled for late 2024. However, progress will remain contingent on the roll out of new electricity transmission infrastructure so miners can harness cheap power from newly commissioned hydropower facilities. Guinea could learn from Namibia, which is looking to leverage its emerging green hydrogen industry to produce direct reduced iron (DRI). This offers a route to decarbonise iron and steel production – which accounts for some 7% of global carbon emissions – since DRI is ideal for electric arc furnaces, used to manufacture green steel.

Economy and business

4. Slowdown forces pivot

In 2023, African economies remained resilient, even as a global economic slowdown weighed on investment in infrastructure and tech, both of which had constituted major sources of FDI. 2024 promises to see increased Western engagement in infrastructure, and greater self-reliance in the tech space.

Continental growth continues to confront major headwinds in the form of elevated inflationary, interest rate and exchange rate pressures. The surge in global interest rates and retreat of capital to safe havens – coupled with the persistent perception of Africa as a “risky” investment destination – have deterred financial flows to the continent over the last year. However, the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment promises to showcase the West’s ability to compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. US and EU funding will finance upgrades to the Lobito corridor – which runs 1,750km from Angola on the Atlantic Ocean to the Central African Copperbelt. This promises to halve overland transit times for Congolese, and eventually Zambian copper, while also expediting shipping to North America and Europe.

Historically a driver of FDI, Africa’s dynamic tech sector has grappled with funding shortfalls, high interest rates and rising operational costs over the last year. This has forced several high profile African startups to scale back on their ambitions and diversify funding sources to ensure long-term sustainability. Opportunities for growth still persist amid regional economic integration drives, embodied by the African Continental Free Trade Area and the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS). At present, PAPSS is gaining ground in Anglophone West Africa, where it promises to offset the dominance of the US dollar, euro, and CFA franc, as well as in East Africa, where Ethiopia is poised to integrate the system, while Kenya hopes to host the secretariat.

5. Rising food insecurity

2023 saw high inflation become the new normal across the continent, driving up living costs. African nations are suffering some of the highest inflation rates globally, with a regional average of 18.5% in 2023 – the highest in 25 years. The suspension of the Black Sea Grain initiative has kept international commodity prices elevated over the last year, complicating imports for African nations.

While the picture is more favourable in the West and Central African CFA franc zones, thanks to currency pegs to the euro, elevated inflation has become the norm in a number of other countries. Sierra Leone, Ghana, Nigeria, Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Burundi, DRC, Malawi and Zimbabwe are all experiencing 20% inflation – a dynamic which risks wiping out household savings, complicating regional trade, and forcing increasingly precarious living standards.

Food insecurity is set to deteriorate. An estimated 160 million Africans already suffer from acute food insecurity, representing about 13% of the continental population. In 2024, 17 million citizens (9% of the population) – of which over 1 million are children – will be at risk of severe food insecurity. The situation is particularly dire in northern Nigeria, where approximately 700,000 children under five years old face life-threatening acute malnutrition. In the DRC, a further 25.8 million citizens – equal to a quarter of the population – are currently experiencing crisis or emergency levels of food insecurity.

6. Debt defaults loom

As predicted, 2023 was a year of protracted debt restructuring negotiations, punctuated by breakthroughs and setbacks. 2024 offers the prospect of redemption for the G20’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments, but also holds the possibility of sovereign default where African states are unable to rollover outstanding bonds.

Zambia’s debt restructuring highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of the G20’s Common Framework. On the plus side, this enabled Lusaka to engage the Paris Club of Western lenders and Chinese policy banks simultaneously, while also benefiting from financial support from the IMF. However, its ability to deliver a viable deal remains unclear. In June 2023, Zambia struck a deal with official creditors, leveraging an innovative model which provided for repayments aligned with the country’s economic performance. This was quickly followed by agreement with bondholders in October 2023. However, official lenders, including the IMF and China, rejected the prospect of bondholders receiving cash back sooner under the baseline scenario. This leaves Zambia without a deal more than three years after it defaulted, indicating that negotiations will continue well into 2024.

The future of the G20 Common Framework altogether rests largely in the hands of Ghanaian Minister of Finance Ken Ofori-Atta. After defaulting in November 2022, Ghana was quick to secure IMF backing for its external debt restructuring proposals under the G20 Common Framework, with lenders forming a creditor committee in April 2023 and the IMF disbursing funds in May. However, progress has since stalled and elections in December 2024 threaten to derail negotiations as fiscal discipline inevitably slips and the political temperature rises.

Meanwhile, as local currencies depreciate against the US Dollar, debt servicing costs are becoming increasingly unaffordable, forcing governments to instigate austerity measures in a bid to avoid default. In Kenya, President William Ruto ordered a 10% cut in government budgets in order to balance the books, but additional sacrifices lie ahead as the country remains locked out of global debt markets on account of high lending rates, which will complicate efforts to repay the USD 2 billion Eurobond maturing in June 2024. In the meantime, Ethiopia looks likely to default on its USD 1 billion bond even before the principal falls due in December 2024, after the government failed to make a USD 33 million coupon payment citing foreign currency shortages. While the government has a two-week grace period, expiring on Christmas Day, it needs to convince bondholders to extend repayment terms and secure an IMF programme to underwrite the debt restructuring process.

Elections

7. 18 electoral races

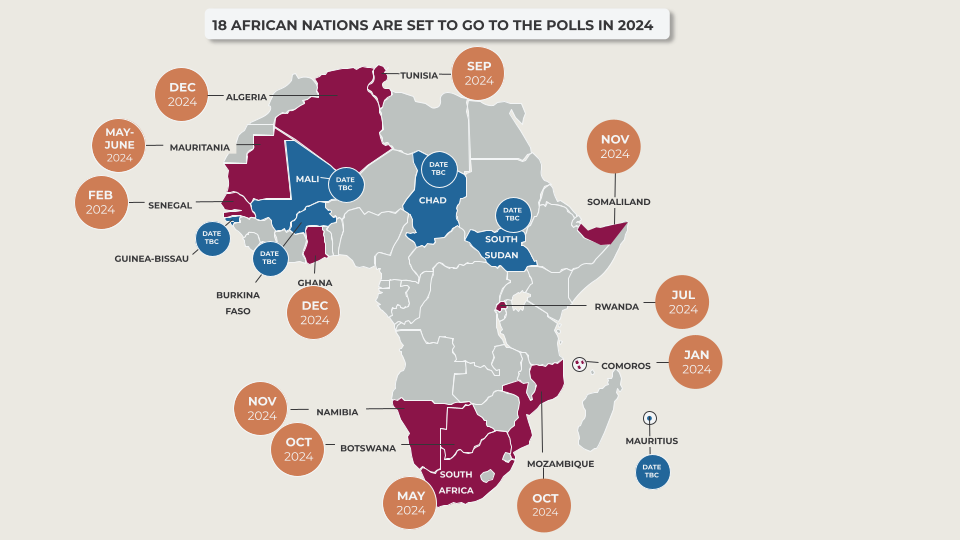

2024 is set to be a bumper year for African democracy, with 18 nations holding elections, as shown on the map below.

Three key races are likely to result in a new president or government:

-

- South Africa’s ruling African National Congress is set to drop below the 50% threshold for the first time since 1994, opening up the possibility of a coalition government. Eight opposition parties have joined a multi-party charter and signed a pre-election agreement determining their political priorities, governing principles, and power-sharing strategy in the event of a hung parliament. But we anticipate political infighting. Coalition governments have been historically unsuccessful at the local level – particularly in the metros.

- Senegal’s incumbent Macky Sall, elected in 2012 and re-elected in 2019, finally confirmed his intention to stand down in July 2023. He is now seeking to install Prime Minister Amadou Ba as his successor, but the former tax inspector lacks Sall’s charisma or political support base. Senegalese are growing increasingly frustrated at efforts to subvert the electoral process by excluding firebrand campaigner Ousmane Sonko from the vote on account of his conviction for “debauching a minor” – a move which has sparked deadly protests. Thus far, the opposition has yet to form a united front, but if it backs a common candidate ahead of the vote, then we would expect polling to go to a second round.

- Mozambique is also due to see a new head of state, with presidential and legislative elections set for October. Voting will take place against a backdrop of heightened political tensions, voter apathy and significant distrust following ruling party Frelimo’s dominance at local elections in October 2023. Polling was marred by credible allegations of fraud and irregularities – culminating in a Constitutional Court decision to overturn a number of results, but leaving Frelimo to govern key municipalities. Such brazen electoral chicanery makes it unlikely that an opposition leader could pose a successful challenge, but much will hinge on Frelimo’s choice of candidate, with a decision expected in early 2024.

8. Pariahs in the Sahel

The wave of military coups d’état continued in 2023, with a putsch in Niger compounding fears that insecurity in the Sahel was driving political instability. 2024 will see the Sahelian juntas increasingly isolated from their peers, as attention turns to Guinea’s planned transition to civilian rule.

Niger has banded together with the military juntas of Burkina Faso and Mali to resist pressure from regional bloc ECOWAS, fearing an intervention by regional power Nigeria. The three military regimes established their own security pact in September 2023. The Alliance of Sahel States (AES) obliges the three nations to provide military assistance to the others in the event of an attack on a member. They deepended the alliance in November, envisaging a broader scope encompassing the political and economic spheres, with the end goal of constituting a “confederation of Sahelian states”.

The AES augurs poorly for the prospect of transitional elections in the Sahel, as Burkina Faso and Mali become international pariahs, unable to secure funding from global partners for votes which had been slated for 2024. This augments the importance of the Guinean transition, which ECOWAS endorsed on the basis it would last just 24 months. This is the basis for US and EU support for Guinea too. Officially, this means elections by the end of 2024, with the transfer to a civilian government in January 2025. Slow progress to date, however, indicates that the Guinean authorities will struggle to implement their ambitious transition roadmap in time, leaving little hope that the country could serve as a model for its Sahelian neighbours.

Security

9. Sudanese conflict endgame

The war in Sudan was highly destabilising for the wider Horn of Africa and Sahel regions in 2023, with displacements exacerbating pre-existing refugee crises in Ethiopia and Chad. While an end to the conflict is likely in 2024, its ramifications are likely to linger in neighbouring states.

The fallout from the war is already complicating Ethiopia’s post-conflict recovery, and it is likely to derail Chad’s ambitious plans for transitional elections in November 2024. The Sudanese conflict has shades of a proxy war, stemming from Saudi Arabia’s support for the SAF and the UAE’s alignment with the RSF, which has discredited Gulf-led attempts to broker peace. Meanwhile, other bordering nations facing complex security issues, including Libya and the Central African Republic (CAR), provide a ready conduit for arms, with the notorious Wagner Group allegedly supplying the RSF with weapons from CAR.

The conflict appears to be entering its endgame, with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) now holding the capital Khartoum, leaving the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) isolated in Port Sudan. This has heightened anxieties in South Sudan over potential damage to the crude oil pipeline that carries the bulk of the country’s exports.

10. SADC-EAC swap in DRC

In 2023, the relationship between the DRC and its eastern neighbours soured further, driven by alleged Rwandan support for M23 rebels. 2024 will see a change in actors, but no let up to the insecurity that has long-plagued the region.

Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi repeatedly criticised the East African Community (EAC) for its failure to eliminate the M23 militia over the last year, culminating in his demand for EAC troops to withdraw if they are unable to fulfil the mission’s mandate. Civilian dissatisfaction with the EAC forces – and UN peacekeepers – led to demonstrations and EAC forces finally began their withdrawal in December. This will be followed by MONUSCO, the longstanding UN peacekeeping mission, which agreed to leave the country in late November, following Tshisekedi’s calls for withdrawal at the UN General Assembly in September.

Tshisekedi is hoping for a more successful partnership with the Southern African Development Community (SADC) in the year ahead, although this is unlikely to address the underlying drivers of the conflict. SADC plans to send in a stabilisation force to help ensure the smooth running of presidential, legislative, provincial and municipal polls scheduled for 20 December 2023 in eastern DRC. The SADC troops are set to deploy imminently, but their presence is unlikely to lend legitimacy to the process. Its mission’s effectiveness will be further predicated on the necessary financial support and adequate resourcing of personnel and equipment. Over a million voters displaced by the conflict are likely to be disenfranchised, having fled their homes without voter cards. In the short-term, the election and arrival of non-Swahili-speaking troops is more likely to inflame tensions than help bolster security, with the conflict in Eastern Congo set to endure well into 2024.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more