CBDCs in Africa: Pipedream or silver bullet?

This week, the Central African Republic (CAR) stole the limelight with its ambitious Sango Coin plan. A healthy dose of skepticism, even cynicism – understandably, considering the country’s macroeconomic fundamentals and broader development trajectory – surrounds the series of announcements by the CAR government. Those have included the launch of Sango Coin as a central bank digital currency (CBDC), an increasingly popular option explored by African states.

Before dismissing them as another fintech fantasy, it is worth exploring what CBDCs can bring (or overpromise) across the continent. CBDCs are, according to the IMF “more secure and less volatile than crypto assets” for a very obvious reason: because they are issued and regulated by central banks.

Surging interest, serious plans

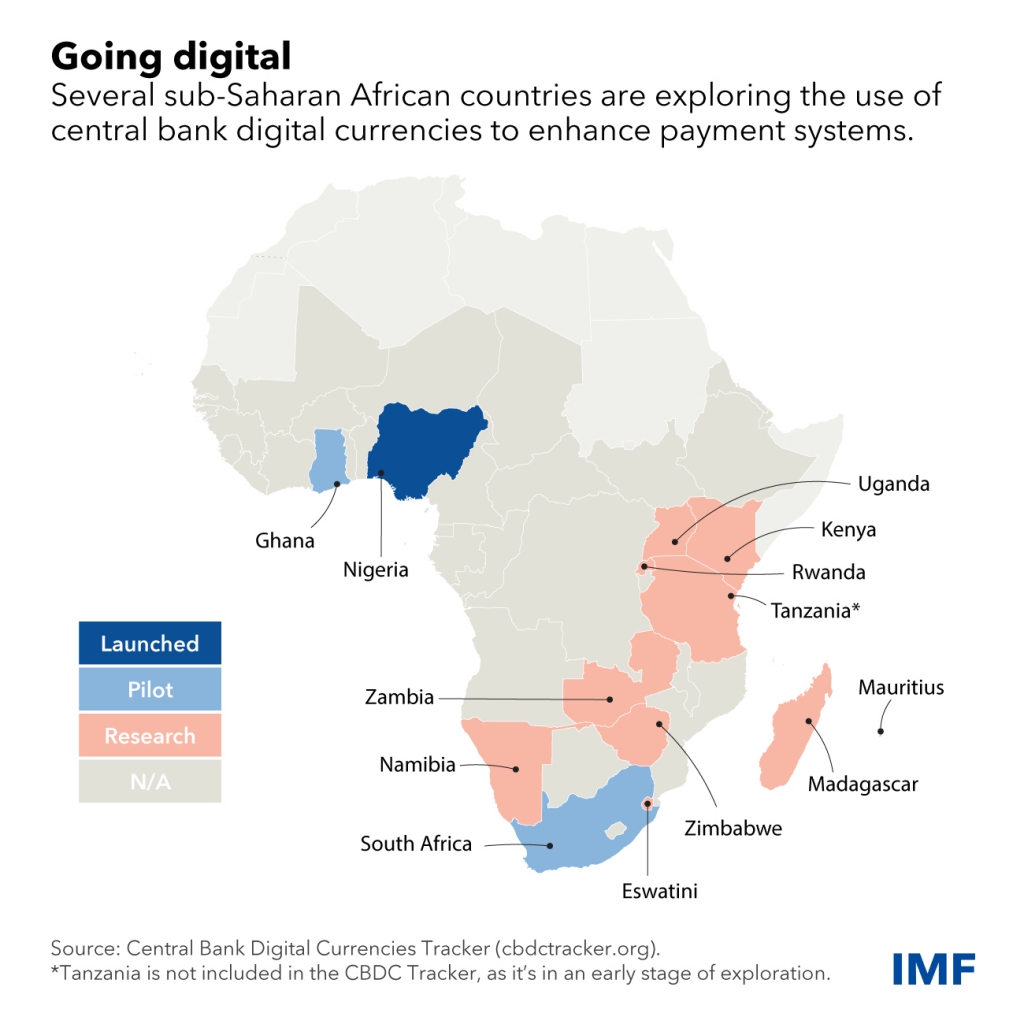

Today, 105 countries, representing over 95% of global GDP, are looking into adopting a CBDC. Interest among African governments is also surging. CBDCs are touted as solutions to pervasive challenges such as lack of financial inclusion, as well as the cost and ease of domestic and cross-border transactions. Last year, Nigeria led the way with its pioneering eNaira, even if its launch has been somewhat disappointing. Ghana and South Africa are already running pilots, with the latter involved in cross-border testing.

Earlier this year, the Central Bank of Kenya launched a landmark white paper on CBDCs, also signalling plans – or at least readiness – for adoption and deployment. Meanwhile, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, Madagascar, Mauritius, Namibia and Zambia are also undertaking research.

Multi-faceted challenges

Rather than narrowly dismissing CAR’s El Salvador-esque ambitions, it is important to critically assess the challenges CBDCs are bound to encounter across sub-Saharan Africa. A number of those were highlighted in our October 2021 UpFront comparatively examining the eNaira, including central banks’ technological preparedness in the face of scalability, and grasp of the country-specific structural issues (where it comes to financial inclusion specifically) that need to be addressed. Without meaningfully assessing the latter, CBDCs can lead to exclusion above anything else.

To consider also is the existence of robust cybersecurity infrastructure, or its establishment, especially in the face of often suboptimal national identification systems that can trip up KYC and AML processes. Data privacy breaches and fraud could also find propitious grounds, targeting populations with lower financial literacy levels.

Meanwhile, cross-border interoperability remains a very nascent discussion, even if it could feed into overarching integration initiatives such as the AfCFTA, for whose operationalisation Afreximbank just renewed its approval of a USD 1 billion facility.

Central banks also need to balance CBDCs adoption with providing leeway for the continent’s booming payments industry. 2021 was a record year for the sector, with 2022 set to surpass impressive milestones such as attracting approximately half of startup funding in Africa, or USD 2 billion.

Without accounting for – and attempting to address – these issues in meaningful consultation with industry and other affected stakeholders, governments and central banks might be subscribing to more of a pipedream than a silver bullet.

About the Author

Margarita is a Director at Africa Practice, where she leads the Intelligence and Analysis team.

Infographic credit: IMF

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more