We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

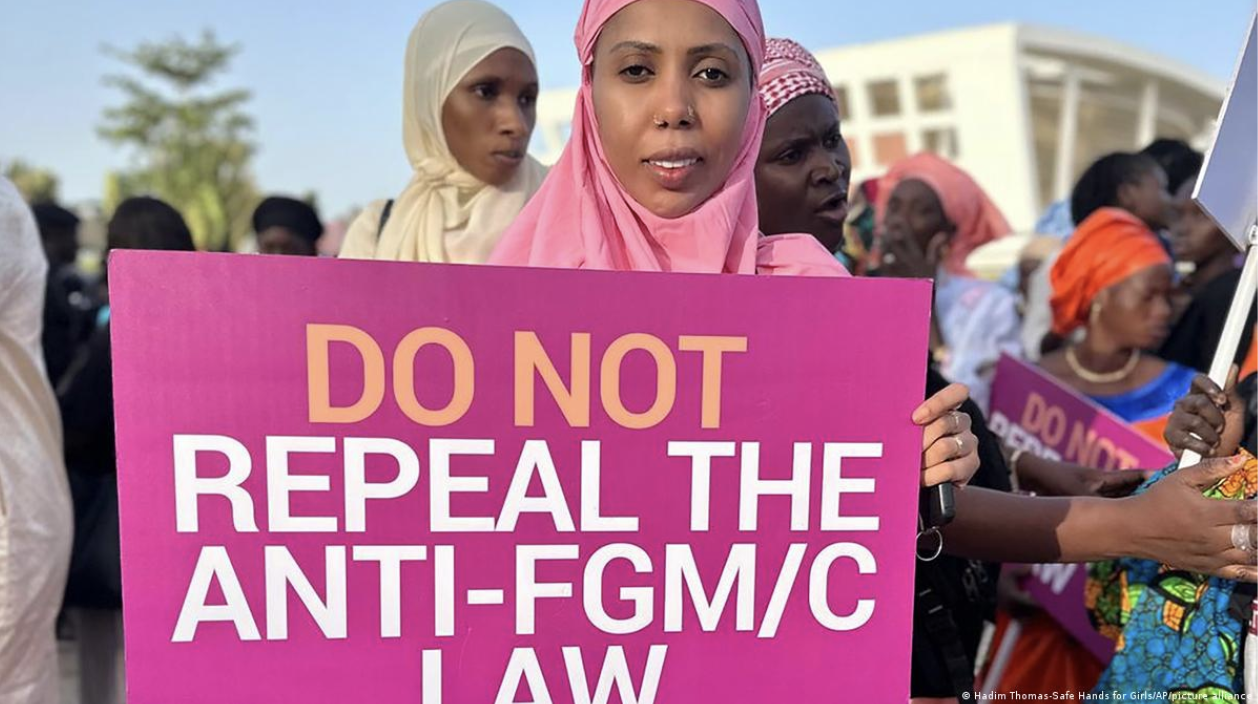

Culture and power: U-turn on FGM in The Gambia

The Gambia is weighing whether to repeal a ban on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). The government outlawed FGM in 2015 by amending the Women’s Act 2010 to prohibit female circumcision. The legal changes followed a campaign by civil society organisations and human rights groups, which had the backing of the majority of Gambian women.

However, controversy arose following the conviction of three women in September 2023 for performing FGM on eight girls under the age of 5 years old. While the amended provisions of the Women’s Act had previously resulted in prosecution of alleged perpetrators of FGM, this was the first successful conviction in a Gambian court.

Going against the tide

On 6 February, independent lawmaker Almameh Gibba introduced the Women’s (Amendment) Bill 2024 to the National Assembly, moving to repeal the 2015 amendments. In doing so, he capitalised on an initial parliamentary statement by Sulayman Saho, a member of the opposition United Democratic Party, who argued, in the wake of the September 2023 conviction, that FGM should be a matter of choice. Saho’s polemic ignited protests in the capital Banjul and a surge in public discourse on female circumcision.

Notably, former interior minister Mai Ahmad Fatty has lent his voice to proponents of repeal, posting in support of FGM on Facebook. Gibba’s bill has also been buoyed by a campaign led by Imam Abdoulie Fatty, who paid the fines of the convicted women and organised rallies calling for the ban’s reversal.

Under the current law in The Gambia, all forms of FGM are illegal under the Women’s (Amendment) Act 2015, with sections 32A and 32B of the act criminalising and prescribing punishments for performing, procuring, and aiding and abetting the practice of FGM. Offenders face up to three years in prison, a fine of 50,000 dalasi (GBP 622), or both, with the possibility of life imprisonment in cases where FGM results in death.

The introduction of legal provisions has been accompanied by shifts in social and cultural attitudes towards the practice. According to a 2020 USAID report, the percentage of women who believe FGM should continue decreased from 65% in 2013 to 46% in 2019-20, with the most significant decline observed among women who have undergone FGM.

However, Gibba’s bill passed its second reading in the National Assembly with 42 of 47 votes on 18 March. Opposition was limited in a parliament with only five female legislators. The bill now heads to a committee for consideration, ahead of a final vote by National Assembly Members, which is expected to take place in June. If the bill is endorsed by legislators, it would then need to be signed by President Adama Barrow, who has thus far been silent on the matter. If the 2015 legal amendments are repealed, The Gambia would become the first country in the world to decriminalise FGM.

Why repeal a watershed law?

In an interview an anti-FGM advocate who herself was cut as a child, asked, “What do they want?… Men, supporters of this barbaric practice, what do they seek to gain?”. The answer is simple: power.

In The Gambia, proponents of repealing the anti-FGM bill often cite religious and cultural grounds to justify their stance. In a society where over 95% of the population is Muslim, religious authorities wield significant influence, leveraging claims that FGM is a virtue of Islam. However, religious arguments against the practice refute this claim, asserting that female circumcision is not mandated by Sharia or considered part of the Sunna.

Nevertheless, influential figures, such as Gibba – who is known for his controversial views, and has been accused of tribalism and misogyny – have spearheaded efforts to repeal the bill. This underscores concerns about underlying motivations. The potential repeal of the FGM law is not merely about politics, health or customs – it is fundamentally about power. The weaponisation of power in society often comes at the expense of women, impacting sustainable development.

The human capital cost of misogyny

The Gambia has seen some progress in gender indicators over the last ten years where, for example, on average, girls outperform boys on the country’s Human Capital Index (0.44 and 0.41 respectively). However, gender gaps, gender-based violence, and the impact of disadvantageous social norms facing women and girls persist, and gains in human capital of women and girls remain untapped.

In The Gambia, 30% of adolescent girls are out of school – below both regional averages (33%) and based on income group (40%). Turning human capital investments into economic gains means addressing multiple barriers to women‘s economic empowerment, including improving their voice and agency. In West Africa, only Mali has a higher prevalence of FGM among girls than in The Gambia, with 73% of girls between the ages of 0-14 years old having undergone FGM – compared to 46% in The Gambia.

Across the continent, FGM prevalence varies deeply, but the practice is particularly prevalent in the Horn of Africa. Over half of girls and women aged 15-49 years old have undergone the practice in Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia. Somalia records the highest FGM prevalence rate on the continent with 99% of girls and women in that age bracket. The absence of female agency, and the extent to which a structure of misogyny and control is perpetuated by both men and women, has adverse consequences on women’s sexual and reproductive health outcomes. In the case of FGM, there is consensus from medical practitioners that any purported benefits are a fallacy. On the contrary, the practice carries both immediate health risks from unsanitary and unsterile approaches, as well as long-term complications including the risk of infertility and fatality.

Women’s rights and rethinking power

Women’s rights activists are concerned about the potential passage of the bill, given the predominantly male and socially conservative composition of the parliament. Deputy Speaker Seedy Njie stands out as one of the few political figures in support of upholding the 2015 ban, citing a commitment from the majority caucus to defeat the bill in a final vote. Yet, this assurance offers little comfort, given that legislators from the majority helped the motion to advance at the initial reading, albeit with 11 out of 58 MPs absent.

President Barrow’s silence on the matter, coupled with reported embargoes on public engagement from ministries and media outlets aligned with his party, has heightened popular apprehension.

If power as domination is the problem then perhaps power as empowerment is a preliminary solution. While political actors remain largely silent, women-led CSOs and international rights groups have taken a leading role in opposing the bill. A coalition of organisations led by The Gambia Committee on Traditional Practices (GAMCOTRAP), the Association of NGOs in The Gambia (TANGO), the Network against Gender-based Violence (NGBV) and other international organisations are urging President Barrow to uphold existing laws against FGM. A policy dialogue in November 2023, facilitated by GAMCOTRAP and the Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Welfare, highlighted the consensus among stakeholders on the importance of strengthening legal frameworks, enhancing enforcement, and raising awareness to combat FGM.

Outlook

As the final parliamentary vote approaches, The Gambia faces a critical juncture. The government can either reinforce protections for women, driving gender equality and fostering positive outcomes such as increased productivity, poverty reduction, and development; or it can regress, by giving into those propagating socially conservative norms and harmful practices.

The Gambia has a complicated relationship with power, in the wake of the 21-year authoritarian rule of former President Yahya Jammeh, where his misogyny was seen as merely an incidental part of his personality. The introduction of the ban in 2015, under Jammeh’s rule, was largely seen as a performative act designed to appease international audiences, rather than indicative of genuine political will to tackle the problem. This undermined compliance with the policy during his reign.

Today, President Barrow’s lack of decisive action on entrenched human rights issues further raises concerns about the country’s commitment to upholding fundamental freedoms and ensuring accountability.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more