Femicide in Kenya and the resounding call for accountability

Femicide, the deliberate killing of women, continues to be a pervasive issue in Kenya, casting a grim shadow over the nation’s progress towards gender equality and human rights.

The persistence of femicide stems from political and cultural dynamics, which enable a prevailing culture of impunity. Perpetrators typically evade justice due to a range of factors, including inconsistent law enforcement as a result of widespread corruption, the weak implementation of adopted laws, and deeply entrenched patriarchal attitudes that trivialise violence against women. Consequently, many cases go unreported or unresolved, leaving families shattered and communities traumatised.

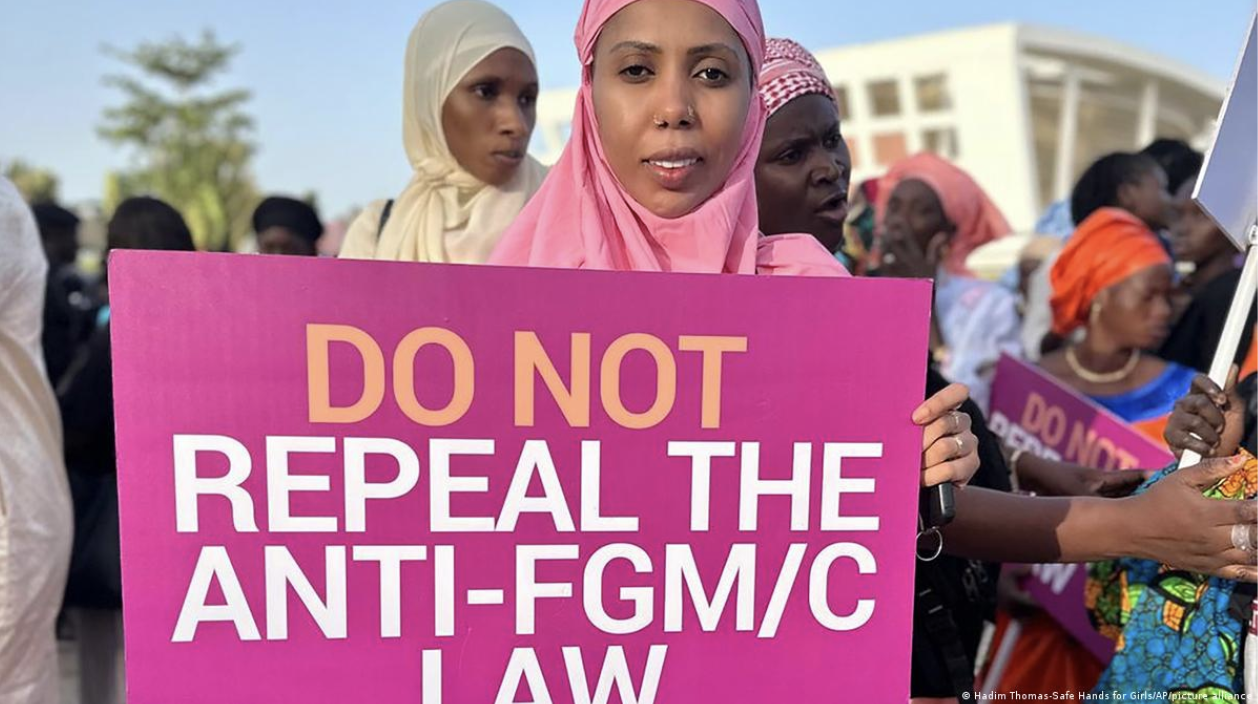

However, the growing frequency of femicide in Kenya has not gone unnoticed, resulting in a resounding call for accountability from various sectors of society. On 27th January, Kenya witnessed a historic turning point in the struggle against femicide as thousands of women, joined by male allies, took to the streets to march against the rising cases of gender-based violence. This significant day marked a coming of age for Kenyan civil society, as the tireless work of Kenyan women activists and organisations paid off.

Yet more work lies ahead if Kenya is to build a culture of accountability to address femicide. This will require a concerted effort from all levels of society, including government, law enforcement agencies, civil society organisations and community leaders. Central to this effort is holding perpetrators accountable for their actions and ensuring justice for victims and their families.

A global challenge

Beyond Kenya, efforts to combat femicide have gained momentum in recent years, driven by increased awareness, advocacy and international commitments to gender equality and women’s rights. One notable example is the Istanbul Convention, a landmark treaty of the Council of Europe aimed at preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Furthermore, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include targets related to ending violence against women and girls, highlighting the global recognition of femicide as a critical human rights issue.

Such texts have provided a framework for states endeavouring to tackle the issue, while also being adopted by non-governmental organisations active in the space. Indeed, civil society continues to play a critical role in addressing femicide in societies worldwide by providing essential support services to survivors, raising awareness about the issue, advocating for policy reforms and mobilising communities to act. Operating at grassroot levels, in many countries, civil society groups provide counselling, legal aid and shelter to survivors while educating the public about their rights. Civil society also regularly collaborates with governments and international agencies to prevent femicide, promote gender equality and enforce accountability.

The Kenyan context

Successive Kenyan governments have taken steps to address femicide through legislative reforms. The Sexual Offences Act (2006), passed under the presidency of Mwai Kibaki, established mechanisms for prosecuting offenders, while the Protection Against Domestic Violence Act (2015), adopted by the Uhuru Kenyatta regime, promoted legal protection for victims of gender-based violence. Following the nationwide marches that took place in January, a public petition by women against femicide was presented to the government in February demanding sixteen points of action.

As it stands, Kenya is struggling to keep up with its regional peers, such as Ethiopia, Tanzania and Rwanda, where female heads of state and legislators are confronting deeply entrenched patriarchal cultures and establishing more permissive environments for women’s rights. Such progress is also visible at the continental level, with the African Union’s Agenda 2063 framework acknowledging the need to address femicide as part of its wider push for gender equality and women’s rights. This initiative entails targets to eradicate all forms of violence against women, including femicide, through strengthening legal frameworks, ensuring access to justice and fostering gender-sensitive policies.

In Kenya, women’s representation in government decision-making positions falls significantly below parity, with women occupying less than 30% of such roles.

Falling behind

Despite these efforts, challenges remain in addressing femicide in Kenya. The country’s lag in combating femicide stems from two political and cultural shortcomings.

Firstly, in Kenya, women’s representation in government decision-making positions falls significantly below parity, with women occupying less than 30% of such roles. This under-representation hampers the inclusivity of policy making processes and impedes the advancement of gender equality agendas. Consequently, the voices of women are often marginalised, hindering the enactment of laws and policies that prioritise efforts to address gender-based violence. Furthermore, while there are women representatives in government, their efforts to pass laws targeted at eliminating femicide often fall short, mostly due to limited political power, inadequate resources or societal pressures.

Secondly, prevailing societal orientations that perpetuate patriarchal norms and tolerate violence against women impede progress against femicide. These ingrained attitudes not only undermine efforts to change legislative frameworks but also contribute to a culture of impunity where perpetrators of femicide often escape accountability. Overall, Kenya’s struggle against femicide reflects systemic challenges in achieving gender equality and addressing deeply rooted societal norms that perpetuate violence against women.

A way forward

If Kenya is to make headway, the government, civil society and the private sector must actively participate in mentoring and educating men from different demographics to foster a cultural shift. The state will also need to make investments in the space. For instance, to expedite access to justice, Kenya will need to hire more police to investigate crimes against women, and support them with training and mental health programmes. The judiciary, in turn, must expedite trials to ensure perpetrators are swiftly brought to justice, thereby addressing the culture of impunity and deterring further crime.

Leadership will also be required at the highest levels of government. The women’s march on 27th January was a collective roar against the deafening silence from the state that has allowed femicide to fester. However, it failed to draw a response from the Ruto administration, with former prime minister Raila Odinga the only prominent political player to engage with the issue. This falls short of activists’ demands for a presidential declaration on violence against women and femicide, as a commensurate response to the national crisis, in addition to calls for ongoing reports on measures taken to address both issues on an annual basis as part of the constitutionally mandated State of the Nation address.

With perennial oppositionist Odinga seemingly on the verge of being co-opted, Kenyans will be waiting to see whether he is willing – and able – to convince the Ruto regime to declare that femicide will not be tolerated, that justice will prevail, and that every life lost will be a catalyst for change. If not, then there are bound to be more days like 27th January, with Kenyans marching in support of political and cultural change.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more