We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Getting the best out of the West: A deeper understanding is required

As global demand for energy transition minerals like cobalt, copper, lithium, and rare earths surges, countries in West Africa are seeking to leverage their natural resource wealth to secure a greater share of the economic benefits.

Requirements for mining companies to invest in local processing and refining capabilities, as well as transport and energy infrastructure, are becoming more commonplace as African nations aim to capture more of the value chain and ensure their populations benefit from the energy transition.

Infrastructure deficits

Infrastructure deficits, including inadequate transportation networks, utility, and energy supplies, remain a binding constraint in the region. West Africa has the highest comparative international transport costs, with the average cost to transport a container being 1.5 to 2.2 times higher than the global average, coupled with one of the lowest rates of electricity access in the world, dominated by fossil fuels.

To overcome these challenges, cashstrapped governments are resorting to public-private-partnerships and co-development agreements to finance, construct, and manage critical mineral infrastructure, with the aim not only to promote mining exploration and development of new resources, but also to catalyse new industries and markets to spur industrial and economic transformation and increase their nations’ share of revenues and jobs from critical minerals value chains.

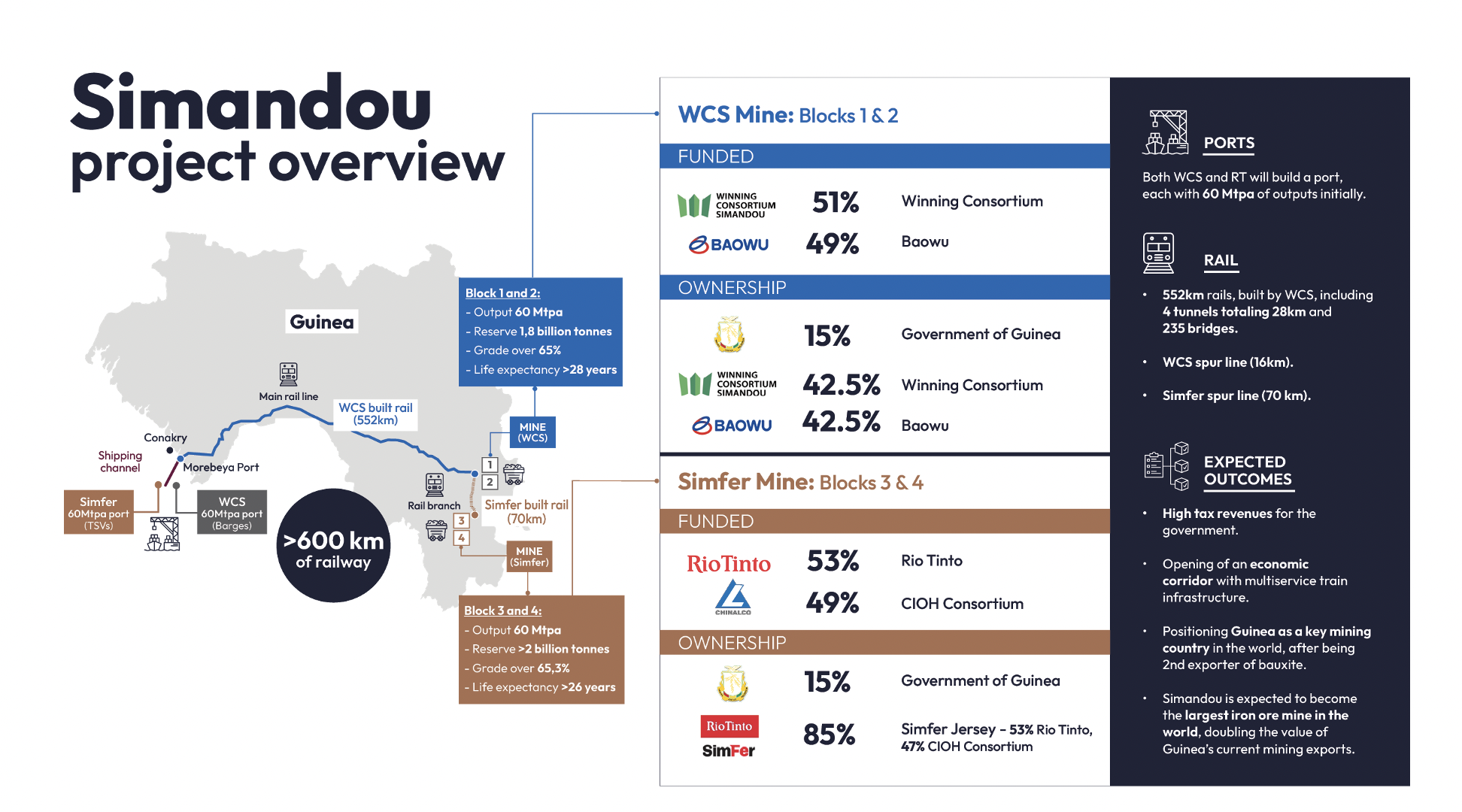

Guinea In Guinea, the completion of the TransGuinean railway is advancing under a joint venture between the government, Rio Tinto Simfer, and Winning Consortium Simandou, with Baowu now also a significant investor. This $18 billion project includes over 600 km of railway and associated shipping infrastructure to evacuate high-grade iron ore from the Simandou mountain range.

Exemplifying the desire to encourage local processing, the Guinean government has struck a deal with Guinea Aluminium Company (GAC), a unit of Emirates Global Aluminum, for the construction of a $4 billion refinery with a production capacity of one million tonnes of alumina per year. GAC announced in June that it plans to work with other companies in a joint venture to progress the project.

In other junta-run nations in the region, notably Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Chad, Russia is emerging as the preferred partner, displacing traditional allies like France and the United States.

Russian foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, travelled to the region in June to discuss military, energy, and mining agreements. Russia’s state nuclear company, Rosatom, is reported to be speaking with Niger’s military-led authorities about acquiring assets held by France’s Orano SA. The Wagner Group, now under direct control of the Russian military, is widely believed to covet the Loulo-Gounkoto gold mine operated by Barrick Gold in Mali.

Liberia

Liberia’s new president, Joseph Boakai, has received a flurry of prospective mining investors since he assumed office in January. Canadian company, High Power Exploration (HPX), announced plans for the Liberty Corridor, a $3-5 billion project that would create a dedicated evacuation route for the high-grade Nimba iron ore deposit in Guinea, which is owned by HPX’s subsidiary.

However, concerns about the project’s viability have been raised, as it may infringe on the rights of ArcelorMittal, which operates the existing railway between its Yekepa mine and the Port of Buchanan in Liberia. Complicating matters further, the authorities in Guinea have expressed a desire to see Nimba iron ore evacuated via the TransGuinean railway.

Senegal

Following the inauguration of President Bassirou Diomaye Faye, the new Senegalese administration announced plans to conduct an audit of the extractive sector. The expectation is for auditors to focus on potential imbalances that may have favoured private interests over the government’s, including operators’ adherence to local content provisions, fiscal obligations, and the 2016 Mining Code.

Nigeria Nigeria’s mining sector is experiencing an influx of interest and investments in the discovery, exploration, and production of lithium and gold. To develop the country’s lithium value chain, the Nigerian government has stipulated that no company will be allowed to mine and export raw lithium unless they establish processing plants within Nigeria.

This policy has seen some early successes, with Chinese companies, Ganfeng Lithium Industry and Avatar New Energy Materials Company, establishing lithium processing plants in the country.

Gold

West Africa attracts the most gold exploration spend after Australia and North America, with more than 79 million ounces of gold discovered in the past decade, the most of any world region.

Endeavour Mining, listed in Toronto, has emerged as the largest gold producer in West Africa, with its recent unveiling of the Tanda-Iguela prospect in Ivory Coast, which it described as the most important find in the region in years.

Ghana is the top African gold producer and the 11th biggest producer globally, with four million ounces in 2023.

President Akufo-Addo remains intent on seeing the construction of a gold refinery and has mandated that all gold refineries operating in the country must sell 20% of their refined gold output to the Bank of Ghana as part of the government’s strategy to increase domestic gold refining and reduce the loss of revenue due to refining abroad.

But without accreditation to the LBMA Good Delivery List, local miners won’t want to sell their gold to Ghanaian refineries and the president’s ambition will remain a pipedream.

A complex environment requiring new skills

West Africa is now a focal point for intense geoeconomic competition as major powers like Russia, China, and Western nations vie for access to a stable supply chain of cobalt, copper, lithium, manganese, iron ore, and rare earths.

The region’s rich mineral endowment and strategic location make it an attractive destination for investors from traditional mining players as well as new entrants from countries like India, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, who are all poised to commit further investment.

However, insecurity, political instability and the imperative for African nations to onshore mineral processing to capture more value domestically and create more jobs, are presenting investors with a complex operating landscape that influences commodity prices, infrastructure, regulations, and the overall investment climate.

These challenges are compounded by divergent goals, disparate organisational cultures, and significant knowledge asymmetries that exist between private investors and governments, over and above the complex web of stakeholder relationships that corporate boards need to maintain a mining licence.

To successfully navigate this landscape, the mining industry must develop a deep understanding of the underlying structures, cultures, and incentives that drive the political economy. They must engage within the system to shape mining policy and to guide individuals and institutions toward beneficial outcomes.

This article was originally published by Mining Review Africa, and is republished here with permission. Image credit: Rio Tinto

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more