Illicit financial flows as a source of development funding

Dominant narratives surrounding Africa’s development focus heavily on the continent’s need for – and reliance on – external sources of finance, at the expense of homegrown solutions. Over the last decade, Africa’s partners have called for development finance to be more sustainable and geared towards self-reliance. In practice, governments across Africa continue to rely on development finance or borrowing from global capital markets to fund infrastructure and provide healthcare and education to their youthful and growing populations.

The human cost of capital flight

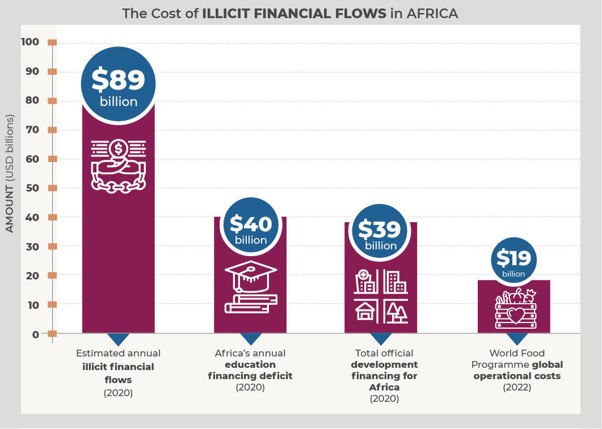

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) on the continent offer a potential source of finance that could be leveraged to address deficits in education budgets, development project financing or humanitarian responses The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that up to USD 88.6 billion is lost to IFFs yearly in Africa, challenging the widespread perception that the continent is a net debtor. Estimates on the exact amount African countries lose to IFFs are difficult to determine. UNCTAD’s figure includes information from identifiable instances of trade mispricing, tax abuse, cross-border corruption, and transnational financial crime. Other estimates are even higher and above the USD 100 billion mark.

Note: Total official development financing for Africa refers to net bilateral ODA flows from all DAC members.

The COVID-19 pandemic and war in Ukraine have highlighted the vulnerability of African economies and the fickle nature of non-domestic sources of financing. As Western countries also grapple with the economic impacts of the last couple of years, humanitarian initiatives, in particular, have taken a hit as their regular sources of funding are reallocated to more pressing priorities. Against this backdrop, tackling IFFs offers a potential long-term and sustainable source of financing for countries across the continent.

Recovering stolen assets and preventing IFFs

While IFFs are an international phenomenon brought about by globalisation, least developed economies are particularly vulnerable to their impacts. The UN’s Financial Accountability, Transparency, and Integrity Panel (FACTI) has described the global financial system as “skewed”, where gaps, loopholes and authorities turning a blind eye create the right conditions for IFFs.

Countries face significant challenges when attempting to track and recover stolen funds that have been transferred to international financial institutions through sophisticated schemes. This is particularly the case for developing economies, where investigative capacity is limited. In March 2022, Kenya recovered USD 4.9 million in stolen public funds after a 10-year investigation that spanned 12 jurisdictions. Angola aims to recover over USD 24 billion in public funds allegedly stolen under the dos Santos administration, of which USD 11 billion has been recovered from banks in the UK, Luxembourg, and Switzerland since investigations began in 2017.

The complex and lengthy nature of asset recovery makes it an ineffective solution to address pressing issues in the short term. A preventative approach that closes loopholes and implements measures to stem IFFs can be more efficient. Initiatives like Tax Inspectors Without Borders (TIWB) support developing countries to build their tax audit and collection capacities. In the three years following its launch in 2015, TIWB helped mobilise an additional USD 328 million in tax revenues for developing countries, with each dollar invested in the initiative returning up to USD 1,000 in taxes recovered. While new technologies like cryptocurrencies have been criticised for their money laundering potential, their blockchain infrastructure could reduce corruption by boosting accountability and transparency.

Development that prioritises equity and self-reliance requires an acknowledgment of how much more the continent loses than it gains, whether in terms of mineral wealth or stolen funds. Illicit, cross-border flows of money from corruption and crime will continue to hamper Africa’s progress until stronger efforts are made to tackle them, both within the continent and in global financial hubs. Addressing IFFs should be a core priority for policymakers and development practitioners around the world.

About the author

Jasmine Okorougo is an Associate Consultant at Africa Practice with a special focus on political economy across sub-Saharan Africa. She can be reached at [email protected].

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more