We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Africa: 10 trends to watch in 2023

Africa Practice has compiled a list of 10 trends to watch on the continent in 2023, covering geopolitics and climate change, economy and business, elections and security.

Download the full report here, or scroll down to read more.

Geopolitics, climate change and the energy transition

1. Momentum builds for greater African representation in international fora

2023 may see strong advances for African representation in international diplomatic and economic fora. All five permanent members of the UN Security Council (UNSC) – the US, UK, France, China and Russia – have expressed support for the AU to become the 21st member of the G20 in 2023. We should know the outcome by the beginning of September when the G20 Heads of State and Government Summit is held in New Delhi.

There is also mounting pressure, including from US President Joe Biden, for the UNSC to include permanent representation for countries in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. Reform of the council, the most powerful organ of the United Nations, will however face more obstacles and prolonged negotiations than accession to the G20.

2. Frustration over climate change “double standards” set to intensify

The politics engendered by climate change are creating new global fault lines which are likely to deepen in 2023. Frustration among sub-Saharan African states is palpable and growing, as exemplified by leaders’ rhetoric throughout 2022. For instance:

- Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni lambasted European countries for their “double standards” by pivoting to coal to reduce their reliance on Russian natural gas in the wake of the Ukraine war, while refusing to fund new oil and gas projects in Africa. Such hypocrisy made a “mockery of Western commitments to climate targets,” Museveni railed.

- The DRC clashed with governments from the Global North, including the US, over its auctioning of oil and gas blocks in the Congo Basin, one of the primary natural carbon sinks on Earth. Kinshasa increased the number of blocks auctioned and justified its decision based on increased global demand for petroleum as a result of the war in Ukraine. This is intensifying pressure on donors to commit funds to the preservation of Congo’s rainforest.

- Seychelles President Wavel Ramkalawan explicitly highlighted this predicament at COP27. The only reason his country was soliciting investment in offshore oil licences was, he explained, because he believed this was the best way to apply pressure on rich nations and secure adequate financing to develop renewable energy and conserve coastal environments.

The type of contrast drawn by the president of Uganda is becoming an increasingly common narrative, used as leverage to secure more financing (see below).

Financial flows are very likely to continue to be a rallying point for sub-Saharan countries in their relations with the developing world. In addition to highlighting geographic discrepancies in the funding of oil and gas projects, African and other developing countries are becoming increasingly assertive in criticising developed countries’ failures to meet and increase their climate finance commitments. Breakthroughs on this front have been achieved at key international summits, notably at COP26 and COP27, but whether these translate into effective action and additional funding will be scrutinised and increasingly determine levels of trust between states and regions.

3. Resource nationalism rises on critical minerals

Higher commodity prices, persistent supply chain disruptions, and growing green activism by citizens and shareholders have prompted a scramble for the minerals required for the energy transition. Countries with large untapped deposits of cobalt, lithium, nickel and graphite (required for battery storage) and copper (needed for electrical wiring) are becoming increasingly assertive in their attempt to secure additional benefits from mining.

The Congolese and Zambian copper belts have historically been synonymous with resource nationalism, with Western miners unable to swallow the onerous terms and high risks which are more palatable to state-backed Asian rivals. DRC and Zambia are now working together to localise battery production in the region, helping to create new future-facing jobs. Zimbabwe – a longstanding proponent of indigenisation – is also seeking to promote local value addition by imposing a ban on raw lithium exports.

Economy and business

4. Investment turbulence ahead as tech wobbles but China surges

Although the global economy will come “perilously close” to a recession in 2023, according to the World Bank, growth across sub-Saharan Africa is projected at 3.6%. Different countries will exhibit substantial variations on this, however. External turbulence is likely to translate into shifting investment patterns on the continent, with potential renewed interest from Chinese investors, many of whom will be looking to capitalise on international opportunities after three years of travel restrictions.

Following a frantic rush of investments in Africa’s tech sector in 2021 and 2022 some of the continent’s (budding) innovation hubs face a sobering outlook, leading them to focus on getting the fundamentals right, building resilience and diversifying. This is set to play out against the backdrop of regional economic integration drives, embodied by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System, the operationalisation of which remains lagging.

5. Central bankers grapple with inflation

Inflation is set to remain in double digits across much of Africa in 2023. The continent’s high dependence on imported fertiliser and petroleum products will drive a sustained increase in living costs. Fertiliser remains in short supply as the Russia-Ukraine conflict drags on, while the end to China’s zero COVID-19 policy is set to increase energy demand, driving up oil and gas prices.

The picture is not consistent across the continent. Countries boasting high degrees of self-sufficiency, such as Tanzania, have been able to keep inflation at a manageable 5%; those which produce little in the way of staple foods, such as Nigeria, have experienced 20%+ inflation, complicating planning and trade. Meanwhile, regional economic communities which use currencies pegged to international reserve currencies, such as the West African and Central African CFA franc blocs, have been able to minimise their exposure to international dynamics.

African central bankers will have to face a difficult balancing act in 2023. If they raise interest rates too quickly, they risk forestalling anaemic economic growth. But the longer they wait, the harder it will be to contain inflation.

6. Multiple countries face emerging debt crises

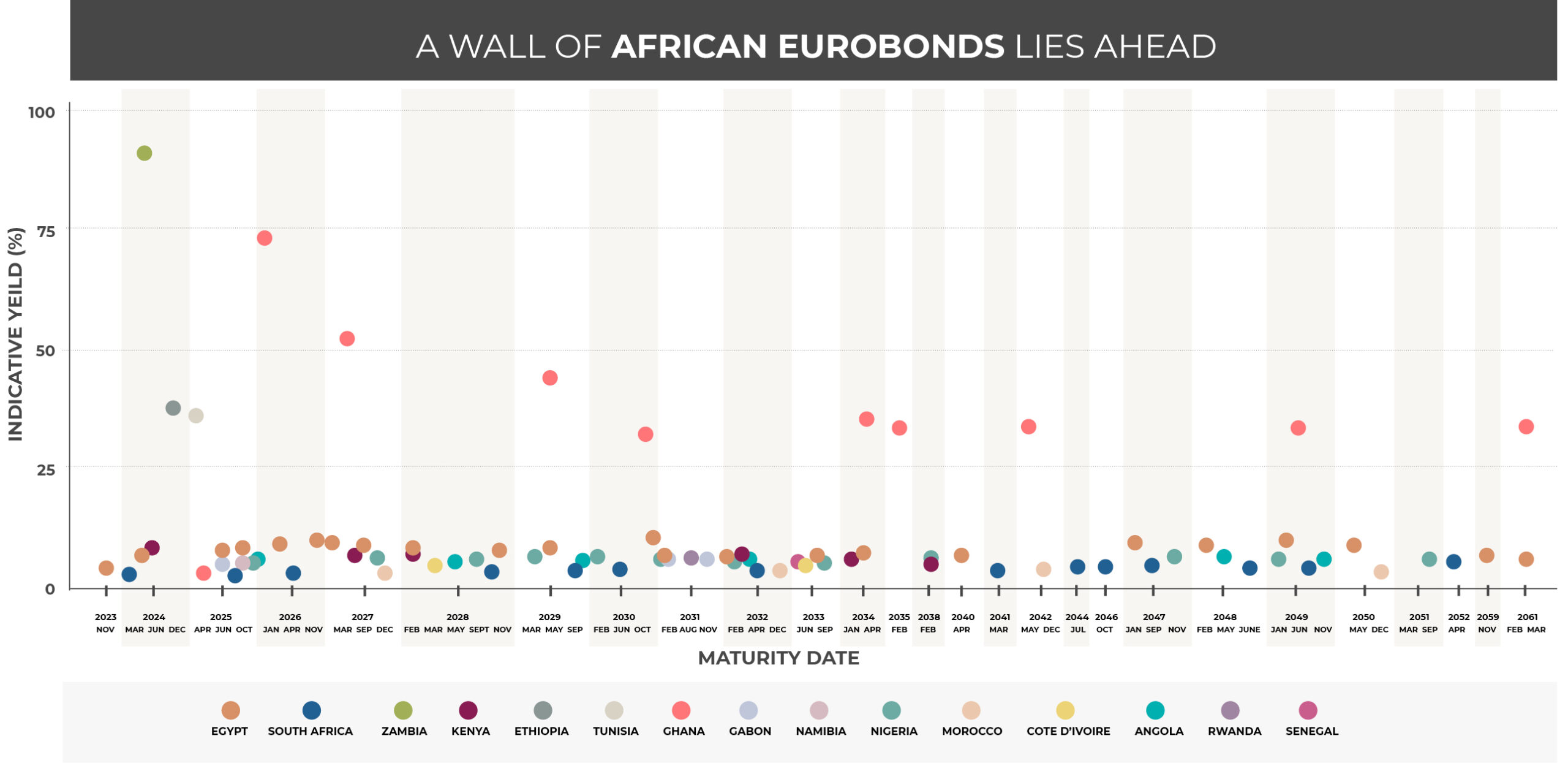

African finance ministers will be watching eagerly as Ghana attempts to restructure its debts and restore its battered public finances, with support from the IMF. Ghana often sets an example for the rest of the continent and 2023 will be no different. Last November, Accra approached its creditors requesting a debt swap, expecting both domestic and international bondholders to accept significant haircuts. The government subsequently suspended foreign debt payments.

Ghana’s sovereign default was years in the making, driven by a binge on costly Eurobonds, excessive expenditure, and limited political will to improve tax collection. Yet, ultimately default came about because of local currency depreciation, which made US dollar-denominated debts more costly to service, and Ghana’s inability to borrow on international markets. These dynamics were brought about by the war in Ukraine and ensuing interest rate rises, which made African securities and currencies less attractive to international investors.

Zambia and Ethiopia are currently in the midst of their own debt restructuring negotiations, utilising the G20 Common Framework, which promised to act as a blueprint for engagement with international creditors. Zambia has made sufficient progress with Chinese creditors that it has secured a IMF programme; Ethiopia still awaits a breakthrough.

With international markets still closed to African borrowers, governments will have to bolster their treasuries before principal payments fall due in 2024. Kenya needs to repay or refinance a USD 2 billion Eurobond in June 2024 – a major challenge for President William Ruto, who ruled out restructuring during last year’s election campaign.

Elections

7. Nigeria will choose its new leadership in a potential run-off

On 25 February, millions of Nigerians will head to the polls for the 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections. Just over a month away from voting day, the presidential contest remains widely open, with several candidates in the running. Four candidates from a total of 18 are the frontrunners: Bola Tinubu of the APC, the party of outgoing President Muhamadu Buhari; Atiki Abubakar of the PDP; Peter Obi of the Labour Party; and Rabiu Kwankwaso of the NNPP. The tight race and emergence of Obi and Kwankaso as possible alternatives to Tinubu and Abubakar – who are the candidates for the two largest and best-established national political parties – create the very real prospect of Nigeria holding its first run-off election.

Whatever the outcome of the 2023 elections, the incoming administration will face a tall order – responding to the uncertain economic outlook and worsening insecurity, as well as providing opportunities and changes for the growing national population, the majority of whom are under the age of 30.

8. DRC insecurity provides pretext for election postponement

Although a general election is officially scheduled for 20 December 2023, President Félix Tshisekedi and his entourage could leverage the security situation in the east of the country – alongside sluggish electoral preparations – to postpone the vote. The 2019 general election – in which Tshisekedi was widely perceived to have been fraudulently declared as the victor – was delayed. The likely opposition and protests a postponement could engender would have important regional repercussions, including on implementation of the AfCFTA, as well as the security situation in the east.

Security

9. New initiatives to tackle Sahel insecurity spillover

The spillover of insecurity from countries in the western part of the Sahel is likely to become more acute in 2023. Militant groups that have long been active in Mali and Burkina Faso are upping their activities further south, targeting Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin. Launched in 2017 to prevent the spread of terrorist threats and enhance security collaboration and cooperation, the Accra Initiative (which incorporates the aforementioned states plus Niger) held its maiden conference in Ghana in November 2022. Government officials and their counterparts from ECOWAS, the AU and EU concluded that terrorist spillover was no longer a risk but a concrete threat, and agreed to collaborate in identifying “home-grown” solutions to contain the spread of violence.

Among the outcomes of the conference was an agreement to form a joint military force to fight jihadist groups in the region within a month, but progress could be undermined by deteriorating bilateral relations. A growing reliance on mercenaries would in turn likely undermine global cooperation against the Sahel insurgency, having already prompted the ongoing withdrawal of French and other European troops from Mali.

In December 2022, ECOWAS military commanders convened to discuss options for a potential regional anti-terrorist and anti-coup force, with a timeframe to establish the operating and funding mechanisms of the force set for the second half of 2023. Mali, Burkina Faso and Guinea were however not involved in the talks. Each country is under sanctions from ECOWAS after one or several military coups in the period from 2020 to 2022 led to undemocratic regime changes.

10. EAC gets bogged down in eastern DRC

More and more states in Africa are weighing into the chronic conflict in eastern DRC in both a diplomatic and a military capacity. In 2022, after it officially became the seventh member of the East African Community (EAC), DRC held peace negotiations in Nairobi with many of the countless rebel groups active. These negotiations were supported by diplomatic talks regrouping EAC member states and held under the aegis of Angolan President João Lourenço. The principal aim of the Angola-mediated talks was to promote dialogue between DRC and Rwanda and to set out a roadmap for the withdrawal of the M23 rebel group, which DRC has long maintained is supported by Rwanda.

To add teeth to the negotiations, the EAC agreed in September to deploy a joint military force led by the Congolese armed forces in the east of the country, marking the first time the bloc is deploying troops to a member state since its re-establishment in 2000. The force could comprise up to 12,000 troops and is operating on a six-month renewable mandate. The involvement of Kenya marks its first major military intervention since it sent troops into Somalia in 2011.

Although there have been some early successes for the EAC-led diplomacy and military processes, any progress achieved in the short and medium term will be extremely fragile and susceptible to breakdown. Previous regional and international forces have attempted to support the DRC to stabilise the region without lasting success, and it remains unclear how the EAC force will coordinate with the ongoing UN mission. Managing relations between DRC and Rwanda will also continue to be a stumbling point. International pressure on Rwanda is likely to mount after a UN report in December 2022 affirmed having collected substantial evidence of Rwanda military activity in DRC territory as well as support to the M23 group, a charge consistently denied by Kigali.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more