We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Methane abatement offers a triple win opportunity for African oil producers

Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas with a major short-term impact on climate change. On a 20-year timeframe, methane has 84 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide, making it an urgent imperative for climate action.

COP 26 saw the launch of the Global Methane Pledge in 2021, with more than 100 nations committing to reduce methane emissions by 30% between 2020-2030. Now, over 150 nations have signed the Pledge, including 44 from Africa. African signatories range from leading oil and gas producing states like Nigeria, Angola, Libya and Egypt to emerging players like Senegal, Mauritania and Namibia.

These nations are poised to become increasingly important as reserves are developed, both for export and to satisfy domestic energy demands. The African Union estimates that 40% of new natural gas discoveries globally were made in Africa between 2011-2021, making industry on the continent a major force in global energy markets.

As an important corollary to increasing production, Africa’s contribution to global methane emissions is also likely to rise. The continent’s share of methane pollution is already estimated to be up to 14% today – well above its overall contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, at 4%. As the development of reserves increases, so will methane emissions.

It is laudable that many African nations have signed the Global Methane Pledge. But, as we approach 2030, progress has been mixed. Only Nigeria, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have developed Methane Action Plans, detailing a pathway to curbing emissions. NNPC is the only African NOC member of the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP 2.0), a UN Environment Programme led effort that promotes strong measurement and reporting practices. And a mere five African national oil companies (NOCs) have signed the Oil & Gas Decarbonization Charter.

Slow progress on reducing methane emissions could hamper Africa’s ability to use methane as a tool to cut climate pollution, strengthen energy efficiency, and increase the economic opportunity of energy development—while aligning with global standards, the evolving expectations of importers and investor expectations.

Methane is the main ingredient in natural gas. Lost methane is lost product. According to analysis from the International Energy Agency in 2025, more than 120 million tonnes of methane is emitted annually by the fossil fuel industry. This is a tremendous waste of an energy resource at a time when the world is scrambling to secure new sources of gas to meet current energy demands.

As African nations develop their energy resources, methane abatement is a unique opportunity to simultaneously boost supplies and stimulate economic development while reducing emissions. It is why Africa Practice and EDF formed a new partnership – and will be in Accra for AOW: Energy – to help producers find ways to leverage methane abatement to advance their energy, economic, and climate goals.

Ensuring access to global gas markets

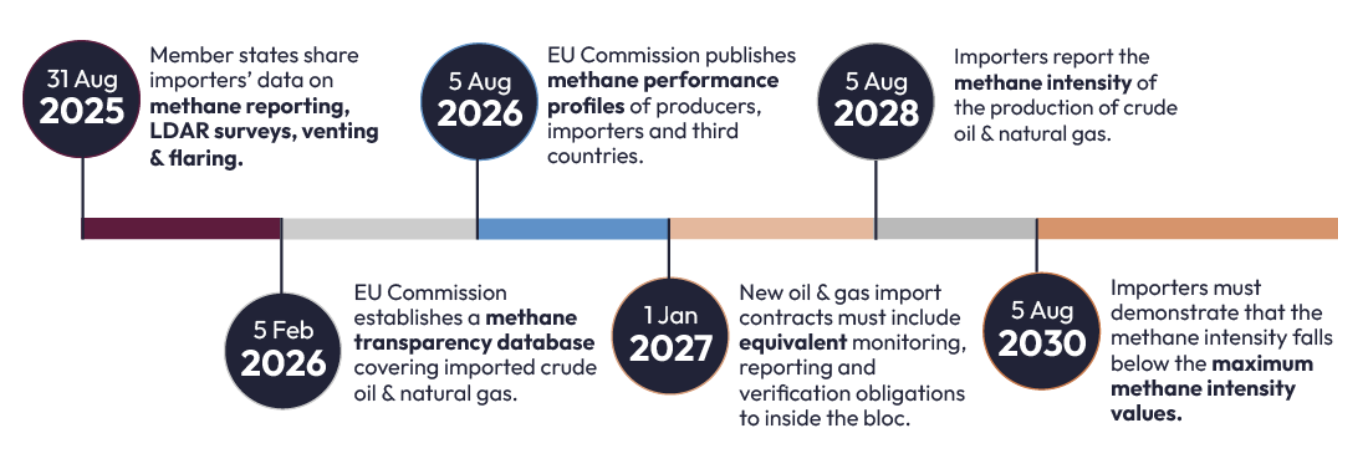

Policy shifts are in different levels of development in key import markets, including the EU, Japan and South Korea. In the EU African NOCs and regulators have a relatively short window in which to engage with Brussels around the implementation of the EU Methane Regulation before key provisions take effect. This flagship policy, adopted in August 2024, will progressively increase MRV implementation and disclosure requirements of importers, before requiring compliance with methane intensity standards from August 2030. In Japan and South Korea, gas importers are being asked to join the CLEAN initiative – a voluntary mechanism to increase transparency around methane emissions associated with imported gas.

By February 2026, the EU plans to launch a methane transparency database for imported crude oil and natural gas; and by August 2026, the bloc intends to publish the methane performance profiles of producers, importers and third countries. All the available information may be used in the assessment of the potential impact of various levels of maximum methane intensity values. The EU is likely to use this assessment to determine the maximum methane intensity values acceptable to the bloc, with imports set to be impacted from August 2030. The EU may consider relevant available information such as that provided by satellite monitoring, including the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P, Japan’s GOSAT 2, and data from specialised organisations such as Carbon Mapper and GHGSat. The International Methane Emissions Observatory, a project of the United Nations Environment Programme, will play a leading role in coordinating the data from these various sources and enabling the establishment of methane emissions benchmarks for each of the world’s major oil and gas producing basins.

Africa and the EU must work together to ensure that the Methane Regulation is implemented in a balanced and sustainable manner. As part of this working relationship, the EU will need to help African governments, regulators and national oil companies to adopt an equivalent approach to methane MRV, and invest in emissions reduction interventions. Such progress is essential to demonstrating equivalence with EU standards to comply with the MRV provisions from January 2027 and intensity standards from 2030. Failure to do so is likely to lead to penalties being imposed.

Innovative financing tools

The EU has yet to announce a dedicated fund to galvanise methane action across the Global South, focusing instead on data collection and research. However, the EU’s pilot scheme “You Collect, We Buy” is currently being trialed in Algeria and Egypt, promising a route to monetising gas that would otherwise be wasted.

Additionally, the bloc has a series of clean energy tools at its disposal. These include Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) and EU Clean Trade and Investment Partnerships (CTIPs), both of which have been pioneered with African partners. Moreover, through the Global Methane Pledge, the EU and its partners have helped to mobilise over USD 2 billion in grants, plus billions more in project finance.

Further funding streams are likely to emerge as Japan and South Korea – both major LNG importers – adopt methane management strategies and policies echoing that of the EU. China, too, is increasingly making responsible methane management a priority.

Waste not, want not

African governments, energy regulators and national oil companies also need to consider the scale of the opportunity presented by methane action. Unmanaged methane emissions should be regarded as wasted resources – a missed opportunity to broaden energy access on a continent where an estimated 600 million people lack access to electricity.

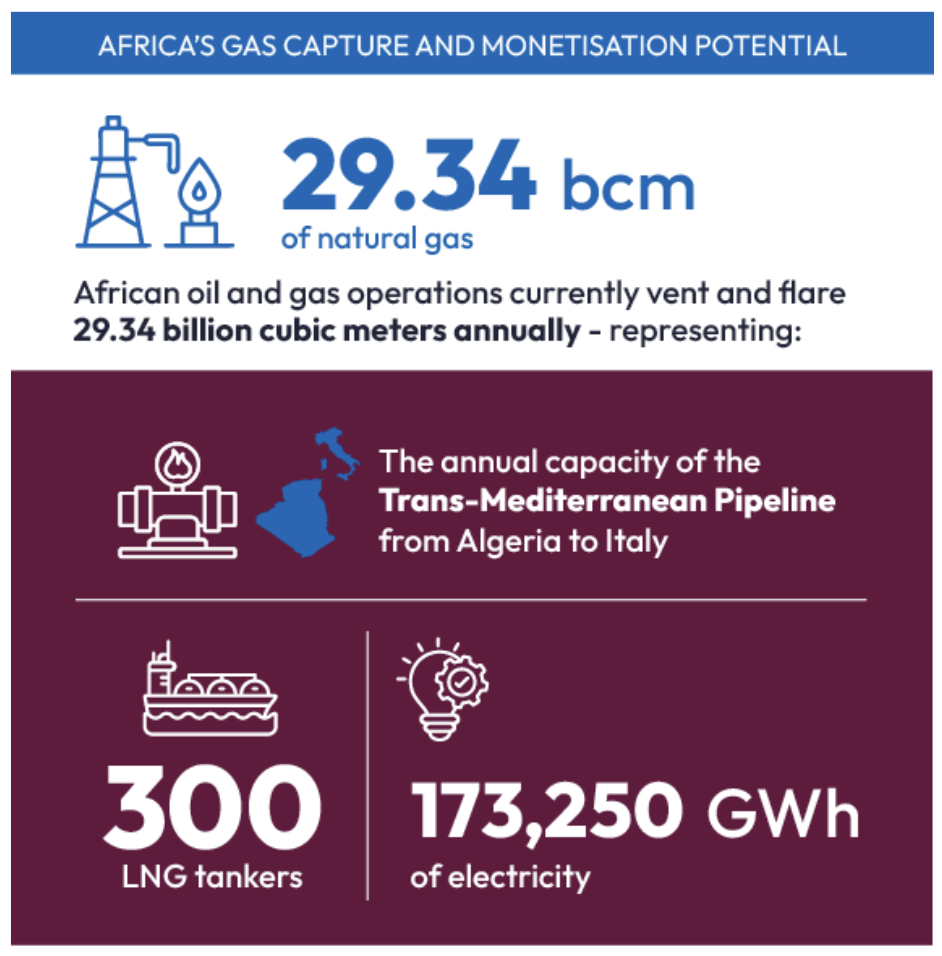

African oil and gas producers flared 29.34 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas in 2024, according to World Bank data. This is equivalent to the total annual capacity of the Trans-Mediterranean Pipeline, which supplies Algerian gas to Europe, via Tunisia and Italy.

If compressed, that gas could fill nearly 300 LNG tankers – comparable to the combined LNG exports of Nigeria, Angola and Equatorial Guinea in 2024.

That amount of energy could generate 161 Terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity at a modern combined-cycle plant – that’s more than 80% of Egypt’s domestic power needs.

While it is hard to calculate the precise scale of opportunity in terms of revenues, given fluctuation in gas prices, long-term contracts and industry secrecy, billions of dollars could potentially be monetised each year by Africa’s oil and gas operators and governments.

As Nigeria has shown in its efforts to reduce gas flaring and venting, captured gas can be monetised, spurring economic growth and broadening energy access. Thanks to gas capture at the Nigeria LNG facility, and spurred by the Presidential Compressed Natural Gas Initiative (PCNGI), the country is increasingly making use of Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) for heavy-duty and passenger vehicles. The Nigerian government is targeting 1 million cars running on CNG by 2027.

Reducing methane waste and capturing natural gas has additional benefits, with propane and butane harnessed for the development of a local Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) market. The Nigerian government supports the use of LPG as an alternative to kerosene, firewood and charcoal, recognising the opportunity to combat deforestation, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and promote cleaner household energy. Such a transition not only addresses the environmental and health hazards linked to wood burning – such as indoor air pollution and respiratory illness – but also boosts demand for captured gas.

Towards a triple win

Action on methane therefore has the potential to advance energy access, strengthen public finances and tackle climate goals simultaneously.

Moreover, the cost of action is relatively small, with investment in leak detection and repair campaigns, installing emissions control devices, and replacing components that emit methane in their normal operations, likely to be covered by savings in terms of monetised gas. According to 2025 research by the International Energy Agency (IEA), roughly 30% of methane emissions from fossil fuel operations could be avoided with no net cost, based on 2024 energy prices.

Development finance institutions are increasingly recognising the imperative to embed methane action in funding criteria. International oil companies, under pressure from shareholders to demonstrate methane action, are also driving action among their joint venture partners. Such collaboration augurs well for national oil companies and indigenous producers, which may otherwise struggle to mobilise finance for addressing leaks, repairing pipelines and replacing pumps, motors and compressors.

Time to act

The urgency to act on both methane mitigation and the development of sustainable energy solutions for Africa is clear. As data on emissions continues to increase, the EU regulatory transition moves into implementation and Africa’s contribution to emissions grows over the coming years – there is a clear opportunity to lead.

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more