We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Show me the money: Kenya’s depleted coffers

“Tighten your belts”, “Prepare for a tough 2023”, and “We are doing our best, but we need time”.

The dramatic change in tone by Kenya’s new government is neither unprecedented nor novel, but it is concerning. As the optimism driven by a rush of popular – and populist – reforms fades away, it is increasingly clear that the majority of the promises made by the ruling Kenya Kwanza coalition will take time to materialise.

The government’s major impediments include crippling foreign debt repayments, a depreciating shilling and a reluctance to follow through on campaign trail promises to clamp down on corruption and tax evasion. A concerning number of political allies and government officials have had their corruption and tax evasion charges dropped during the transition, indicating waning will to tackle graft.

Kenya has both a debt problem and a low return on government spending problem. The pandemic prompted a fresh wave of borrowing, including from the IMF and World Bank, which were quick to extend credit, albeit with conditions attached. The Bretton Woods institutions have become increasingly important as China pared back loans to Kenya in the wake of low returns on previous loan agreements.

Chinese infrastructure loans generate limited returns

This marked a major reversal. During Uhuru Kenyatta’s first term as president (2013-2017), Beijing became Kenya’s largest bilateral creditor off the back of infrastructure loans, with bilateral debt rising from KES 63 billion (USD 554 million) to KES 478 billion (USD 4.2 billion) in five years. Kenyatta’s second term (2017-2022) saw Chinese borrowing increase further to KES 786 billion (USD 6.9 billion) by December 2021; however, this was eclipsed by loans extended from multilateral lenders. The World Bank increased its credit to Kenya to KES 1.125 trillion (USD 9.8 billion), while IMF loans grew to KES 207.5 billion (USD 1.8 billion) by December 2021.

The situation is dire. Public debt is equal to 68.1% of Kenya’s GDP. According to the 2022 Medium Term Debt Strategy (MTDS), public debt stands at KES 7.69 trillion (USD 61.89 billion) against the statutory public debt ceiling of KES 10 trillion (USD 80.48 billion). Total external debt – most of which is dollar-denominated – stands at KES 4 trillion (USD 32 billion), while domestic debt amounts to KES 3.7 trillion (USD 29 billion). In practical terms, for every KES 100 (USD 0.80) netted by the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) in FY 2022/2023, an average of KES 63.50 (USD 0.51) went into repaying debts owed to local and foreign creditors.

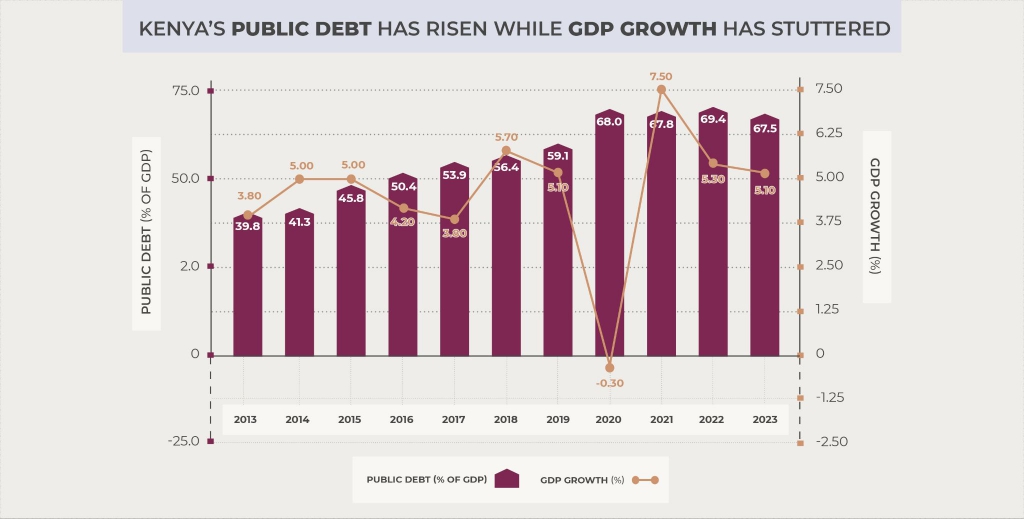

However, the accumulated debt has not paid off by boosting economic growth. Instead, grand infrastructure projects such as the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) have yet to generate a material return on investment. In the chart below, we show how Kenya’s public debt has grown while GDP growth has stuttered.

Ordinary Kenyans pick up the bill for White Elephant projects

The ramifications are becoming increasingly stark for the exchequer – which has sought to pass on the burden to the taxpayer. Saddling wananchi with higher taxes is not a sustainable model. As deputy president, Ruto railed against the government, pointing out how recurrent expenditure and debt ate up almost all revenue, leaving none to invest in growth-boosting capital expenditure. His first six months as president have, however, forced a realisation – the depleted Treasury may have been the previous government’s doing, but it is for Ruto to deal with it.

The government does have a plan, but its feasibility might come under scrutiny. In the recently released draft Budget Policy Statement 2023, the government set out its priority programs, policies and reforms to be implemented in the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF). The Treasury stresses that its fiscal policy stance is designed to support the Kenya Kwanza administration’s economic recovery agenda. The government expects that the diligent application of this plan will boost the country’s debt sustainability position but fails to acknowledge the effects it will have on the average citizen.

This plan, fiscal consolidation, mixed with monetary consolidation – where the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) works to reduce the supply of money in the economy – will undermine economic growth. The cuts to government subsidies and high bank lending rates have left low-income households unable to access key commodities or to borrow at affordable rates. While the Hustler Fund was meant to serve as a stop-gap measure, its utility is constrained by both its high annual interest rate (9.5%) and lending limits. The fund’s first phase allows borrowers to access between KES 500 (USD 4) and KES 50,000 (USD 400) – sums that are insufficient to generate meaningful enterprise and instead encourage a day-by-day dependence on the facility to cater for basic needs.

The government’s plan

As part of the economic turnaround plan, the government will scale up revenue collection efforts, with the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) targeting KES 3.0 trillion in the FY 2023/24 and KES 4.0 trillion over the medium term. In order to achieve this, the government will reform both tax administration and tax policy. Yet the Treasury risks balancing its books on the backs of the poorest, and undermining its own credibility, after the KRA and Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions withdrew a series of tax appeals against Ruto’s allies.

This presidency’s success, perhaps more than any other, is tied to economic recovery. Ruto has made a habit of defying expectations, Kenyans will hope he lives up to his reputation – their livelihoods depend on it.

About the Author

Victor Kimondo Maina is an Associate Consultant at Africa Practice, focusing on the digital economy and the extractives sector. He can be reached at [email protected]

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more