Who is afraid of Twitter?

The Nigerian government certainly isn’t, it seems.

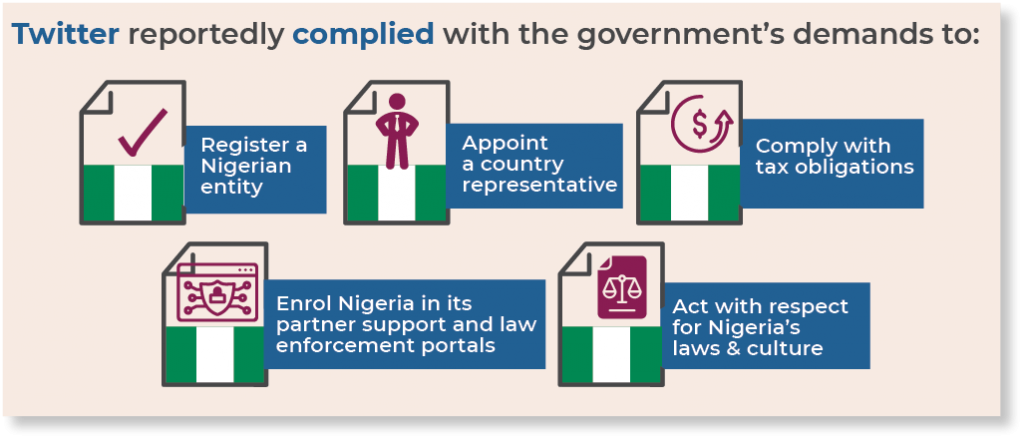

On 5 June 2021, the Nigerian government announced an indefinite ban on Twitter’s operations in the country — ironically via Twitter. Over seven months later, effective 13 January 2022, the government lifted the ban on the basis that Twitter had agreed to meet several conditions imposed.

In the hours following the announcement, reports suggested that Twitter would give the government backend access to take down Nigerians’ tweets. Except, Twitter doesn’t operate that way.

Twitter’s processes

Twitter does have processes for governments, law enforcement and third parties to request that content be restricted or that account information be provided. These processes allow for the removal of tweets, on the basis that domestic laws may have been broken – covering hate speech, defamatory or harmful content. Twitter can also provide user information, for instance, in emergency situations where self or physical harm or terrorism-related offences are suspected. That said, not all of these requests for removals or information are successful. We know this because Twitter publishes this data.

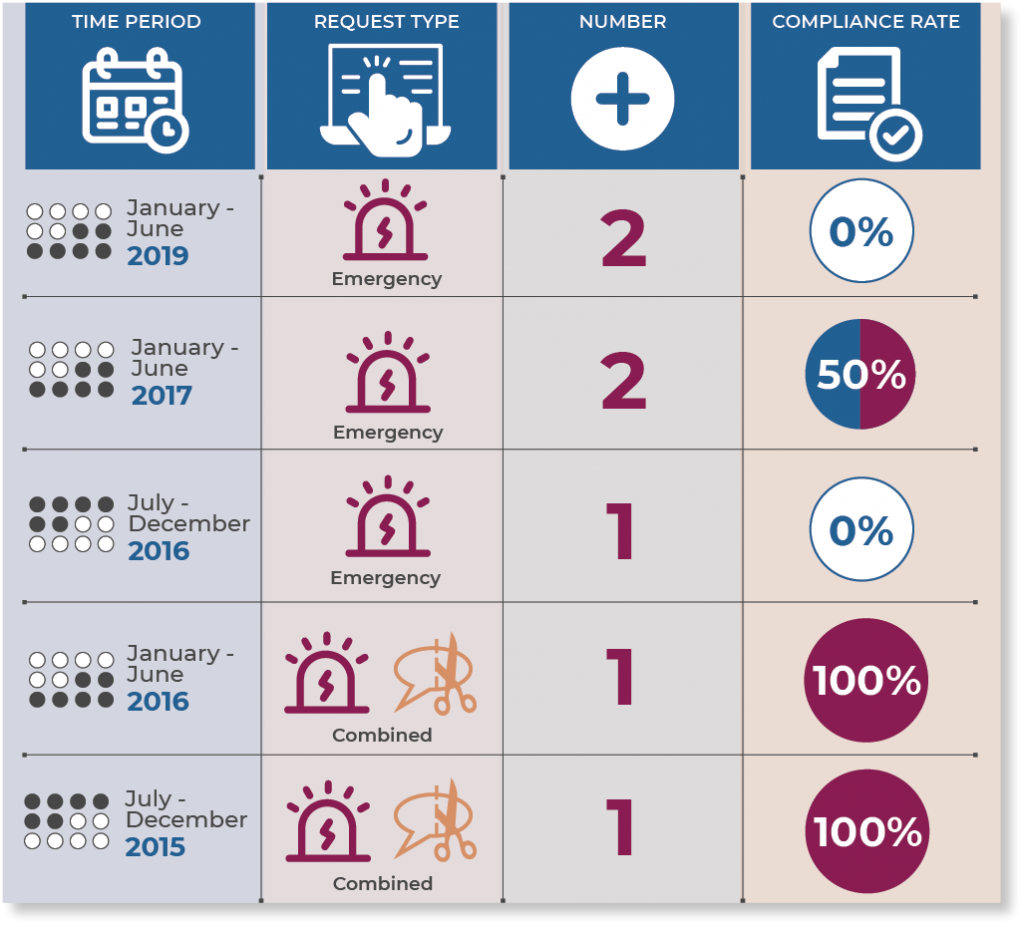

Twitter began publishing a detailed breakdown of country removal requests in 2015, and has provided statistics on them since 2012. By its own reporting, Twitter has received legal demands from 92 different countries since 2012: there were 80,744 removal requests made in 2020 alone. However, Nigeria has not made any removal requests since inception. Nigeria has, however, made seven requests for account information – five of which were classed as “emergencies” with just three successful.

Here’s a summary of that data:

More nuance

One implication of Twitter’s accession to the government’s demands is particularly important. Nigeria does not have a double taxation treaty with the US, which would ordinarily afford it protection from double taxation on its income arising from Nigeria. The 6% tax on turnover for non-resident digital companies, which came into effect on 1 January 2022, is thus even more relevant for companies such as Twitter, where its country-specific revenue cannot be ascertained. New legislation allows Nigeria’s revenue authority to assess what portion of Twitter’s revenue it reasonably expects to arise from its presence in the country.

What next?

The coming year will be revealing. As 2023 presidential elections beckon, the political discourse will likely become more divisive and potentially violent. There will be renewed attempts to restrict politically damaging speech online — even more so than is already the case. Attempts to codify social media regulation through legislation could resurface.

However, legislative reform often relies on small windows of opportunity, and in this instance, social media regulation may take a backseat to politicking — in the absence of aggressive legislative efforts. And even if new legislation is not forthcoming, Twitter’s perceived acceptance of the government’s conditions may encourage attempts to scapegoat prominent individuals under extant national security or cybersecurity legislation – on the basis of their online speech.

All indications are that the government will look to expand its sphere of influence on foreign operators operating within its borders, whether on the basis of data localisation and protection regulations, tax or cybersecurity obligations or indeed national security concerns. As it stands, the Nigerian government has shown that it is not afraid of Twitter, arguably a political entity in its own right.

About the Author

Amaka Yvonne Onyemenam is a Consultant at Africa Practice, focusing on technology policy and the digital economy. She can be reached at [email protected]

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more