We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Recalibrating insecurity responses in Nigeria

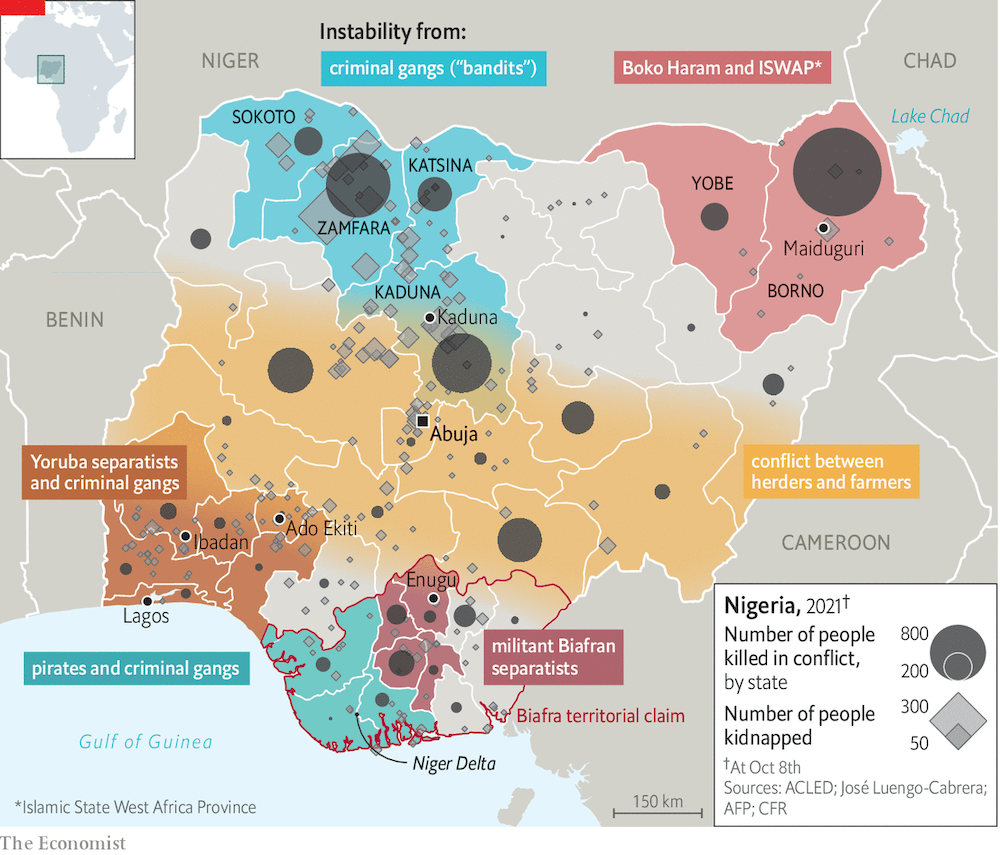

In the past year, insecurity escalated in some Nigerian regions, with increased incidences of terrorism, kidnappings, banditry and other forms of violent crimes leading to numerous casualties, disruption of livelihoods and a record number of ransom kidnappings.

Banditry emerged as a foremost security issue, and remains rampant in the North West and North Central regions with no signs of abating. Over 2,000 fatalities in 935 events were recorded in 2021, with Kaduna, Katsina, Sokoto, Zamfara and Niger states being most affected. Kaduna state alone recorded a 27% increase in violent attacks since 2020. The scale of this security threat led President Muhammadu Buhari to officially proscribe bandits as terrorists on 5 January 2022; as a result, provisions of the Terrorism (Prevention) Act 2011 will now apply to them.

In the North East, sustained terror attacks, poverty and a humanitarian crisis place an estimated 10.6 million residents at risk. Despite the elimination of Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau in 2021, the threat persists with the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) reportedly better armed and coordinated than Boko Haram.

Attacks in the South-South and South East Regions have predominantly focused on security infrastructure and appear linked to the secessionist movement spearheaded by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and the Eastern Security Network (ESN).

Image source: The Economist

Compounding developmental challenges

The proliferation of insecurity has further compounded the developmental challenges facing these regions. Insecurity is exacerbated by other inter-related factors such as the impact of climate change, the proliferation of arms, porous borders and the thriving illegal mining business.

Against this backdrop, there are increasing calls for government restructuring to redistribute power and resources, through a devolution of policing away from the centre to states. This alone is unlikely to achieve desired results of abating insecurity. Affected state governments are thus keen for the federal government to intensify kinetic responses even as the military remains overstretched, with active operations in almost all geopolitical zones.

Insecurity has caused significant threats to the social welfare of Nigerians. Bandits and terrorists have taken advantage of the pervasive poverty and alienation from government services by establishing a social contract with communities, as well as collecting taxes in exchange for security and access to farms and markets. This has allowed them to move and recruit freely in certain communities.

Consistent attacks are impacting a range of development priorities in the region. For example, attacks on schools and students have led to the closure of 618 educational institutions across six northern states by the government. Education is now becoming less attractive to residents, increasing the number of out-of-school children and exacerbating the existing educational imbalance (South-North) in the country. The prevalence of attacks has also deterred smallholder farmers from accessing their land, intensifying the ongoing food insecurity.

Refocusing government and development partner efforts

The government’s response so far has proved inadequate. In September 2021, for example, governors in affected North West states suspended weekly markets, banned the sale of cattle and imposed curfews in the affected local government areas (LGAs). In Kaduna, Zamfara and Sokoto states, the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) shut down telecom operations sites as a security mechanism. But these actions did not bring about tangible results. Both states subsequently rescinded the blockade of telecoms services in October, while others also rolled back heavy restrictions imposed due to the economic consequences and absence of marked improvements in the security situation.

Beyond increasing the efficiency of its security operations, particularly around intelligence gathering and border control, the government has to focus more on identifying and addressing the socio-economic challenges that catalyse insecurity. There needs to be more intentional and large-scale efforts to tackle impoverishment and political marginalisation. This can be achieved through building more viable relationships with community leaders, as well as making strategic investments in human and infrastructure development in afflicted regions.

In light of this, the activities of development partners have become more critical through the additional support they offer in addressing gaps. Through an approach that coordinates multi-sectoral stakeholders and refocuses the national response on these drivers of insecurity, impacted communities can begin a gradual return to normalcy.

About the Author

Gbope Onigbanjo is an Analyst at Africa Practice with a special focus on monitoring and analysing political economy developments in Nigeria. She can be reached at [email protected].

*Header image source: The New York Times

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more