We are excited to announce that Brink is now part of Africa Practice. Learn more

Will Ghana’s Eurobond addiction ruin it for others?

Ghana’s Minister of Finance Ken Ofori-Atta announced plans for a debt exchange programme during his budget presentation on 24 November. His deputy, John Kumah, subsequently clarified that the government would ask international bondholders to accept up to 30% haircuts on principal payments and to forgo interest payments for three years. Domestic bondholders will also be requested to swap their securities for new instruments with less generous terms.

The treasury’s belated acknowledgement that it needed to restructure its debt was a response to a negative feedback loop of local and international dynamics since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine nine months ago. These factors have conspired to make Ghana’s currency – the cedi – the worst performing of the 148 monies tracked by Bloomberg. The cedi has lost over 50% of its value in 2022, making US dollar-denominated debt more expensive to service in local currency terms, and forcing the treasury’s hand.

Global headwinds and Ghanaian pressures

At the domestic level, inflation reached 40% in October, driven by a 70% annual increase in housing, water and energy costs. The country’s rising import bill – notably for refined petroleum products – ate into hard currency reserves just as gold revenues declined and domestic businesses clamoured for US dollars to restart operations after the pandemic. International reserves plummeted from the equivalent of 5 months’ worth of imports to 3 months’ over the period June 2021-June 2022.

On the international plane, Ghana was acutely exposed to the exodus of capital from emerging and frontier market debt this year, as rising interest rates in the global north made more risky jurisdictions less attractive. Investors withdrew a record USD 70 billion from funds investing in emerging market debt between January and the end of September 2022, according to the Institute of International Finance.

Ghana also suffered a series of credit rating agency downgrades, driven by its rising debt-to-GDP ratio in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. When rating agencies placed its sovereign debt firmly in “junk” territory, non-resident investors responded by selling Ghanaian bonds. Each transaction forced the authorities to part with yet more US dollars, further weakening forex reserves and undermining the value of the cedi.

The sell-off also drove up yields on Ghana’s Eurobonds, raising borrowing costs. Spreads between US treasury bonds and Ghanaian external debt have more than doubled during the course of 2022, as investors priced in the growing risk of debt restructuring. As Ofori-Atta admitted before parliament, this combination of credit rating downgrades and high yields essentially locked Ghana out of international capital markets.

From market darling to debt restructuring

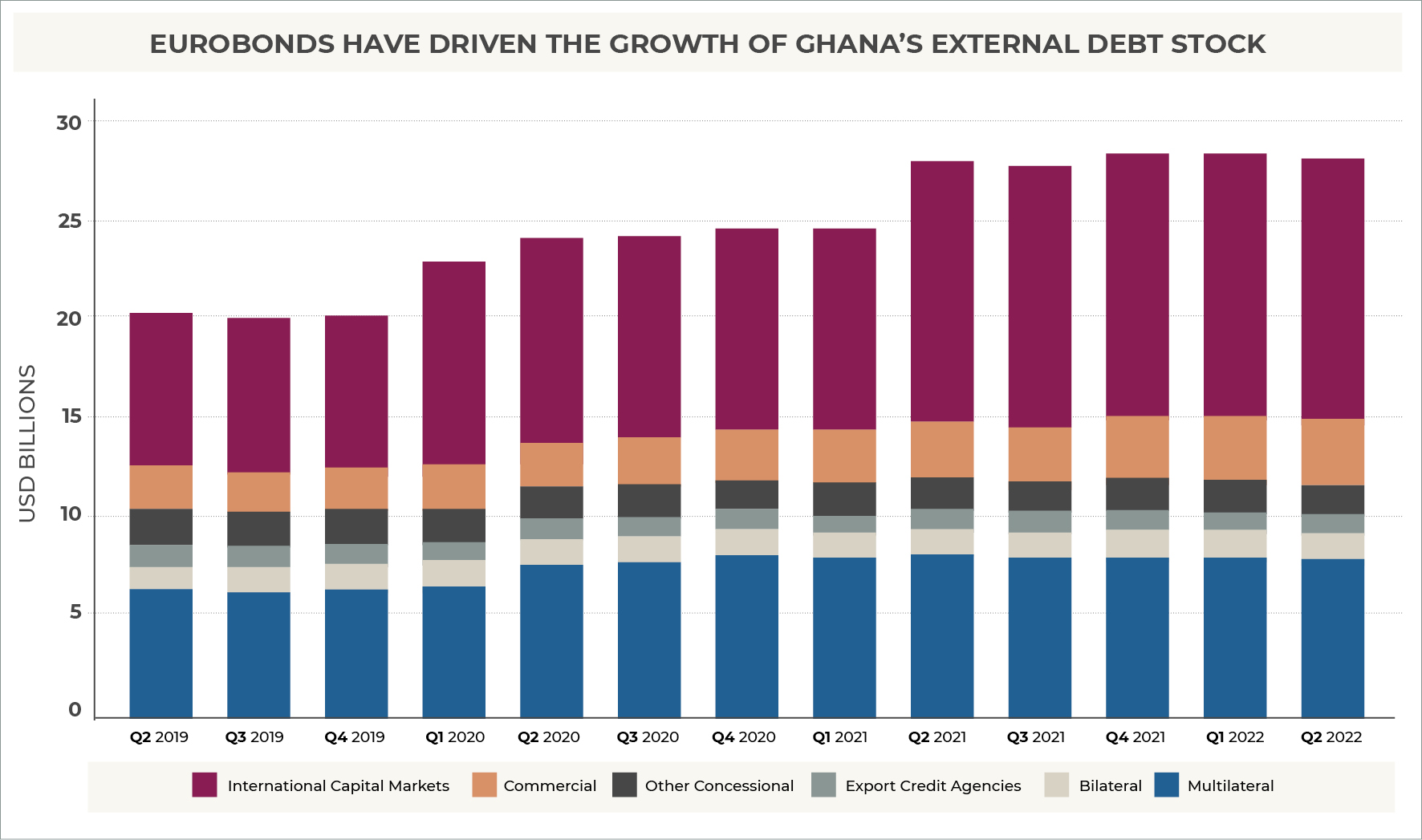

Ghana has been prolific in global debt markets since its debut Eurobond in 2007, and was the first African government to issue a sovereign bond following the COVID-19 pandemic. The country has USD 13 billion of outstanding Eurobonds (see below), making it the top African issuer relative to the size of its economy.

However, Ghana’s Eurobonds carry high debt servicing costs. The government spent GHS 20.5 billion cedis (USD 2 billion) servicing its debts in H1 2022. The problem is exacerbated by Ghana’s low tax base, with revenue collection equal to 11.3% of GDP – well below the African average of 16.6%.

President Nana Akufo-Addo neglected to meaningfully address this underperformance during his first term in office, a decision he may now regret. Although going easy on taxpayers may have eased his path to re-election in December 2020, his New Patriotic Party (NPP) failed to obtain a parliamentary majority, forcing a recourse to pork barrel politics. Ofori-Atta’s solution to the problem had been to “extend and pretend” – to borrow afresh on international capital markets in order to pay off bonds falling due. However, with Ghana unable to issue a Eurobond, the treasury had to approach the lender of last resort.

Back to the IMF

The government is now counting on the IMF to bail it out – for the 17th time! This move marks an abrupt U-turn for President Akufo-Addo, whose “Ghana Beyond Aid” mantra looks to have been premature, and for Ofori-Atta, who vowed that the country would never return to the Fund.

However, Ghana needs to demonstrate to the IMF that its debt is sustainable in order to qualify for a support package. The country has the highest debt-to-GDP ratio of its peers (as illustrated below). Although the finance minister has made it clear the government will not honour its obligations on existing terms, the treasury will nevertheless need to demonstrate that creditors are open to negotiations before it can alleviate its fiscal woes.

Contagion effect

Many African governments will be looking on with interest. Emerging and frontier markets are often the victim of contagion, with a sell-off in one prompting an exit from others. It is clear that investor sentiment turned against African sovereigns well before Ghana’s debt swap was announced. Spreads between the yields on US treasury bonds and African Eurobonds are at 15-year highs, indicating low investor appetite and resulting in high borrowing costs.

Such high yields will keep African governments shut out of international capital markets until next year at least, raising questions as to their ability to refinance loans falling due. Fortunately, only Egypt and South Africa have Eurobonds maturing in the next 18 months, and these are among the two best rated sovereigns. Only South Africa and Morocco are able to borrow at rates below 7.5%, with Egypt close to 8%, according to CBonds data.

However, principal payments are due on a number of African bonds thereafter, starting with Zambia (which has already defaulted on its external debts) in April 2024, and Kenya in June 2024. Days prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Nairobi announced plans to refinance its debut Eurobond – issued at 6.875% in June 2014 – in a bid to capitalise on, what were at the time, low borrowing costs. The treasury subsequently put issuance plans on ice amid market turmoil.

However, if African sovereigns remain unable to access global capital markets into 2024, President William Ruto may have no option but to ask creditors to restructure Kenya’s debts – a step he was eager to rule out on the campaign trail.

Nick Branson is a Senior Consultant at Africa Practice where he advises clients in the financial, energy and mining sectors. The above represents his views and not those of Africa Practice. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Proud to be BCorp. We are part of the global movement for an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system. Learn more